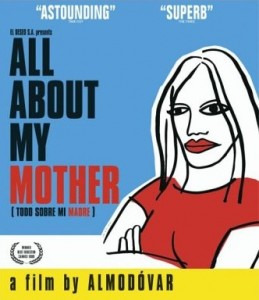

celluloid relapse: all about my mother

Despite any protest asserting the contrary, human beings are remarkably similar. Culture, appearance and whatnot may be paraded around as a supreme marker of difference, but the volume at which we object seems due to a very odd misunderstanding. Primary school tried to tell us we were all different, but fundamentally we were and are anything but. None of us, given the current state of modern science, are some super-foetus grown in a test tube and all of us spent approximately 40 weeks in a uterus. In other words, all of us have a mother.

Despite any protest asserting the contrary, human beings are remarkably similar. Culture, appearance and whatnot may be paraded around as a supreme marker of difference, but the volume at which we object seems due to a very odd misunderstanding. Primary school tried to tell us we were all different, but fundamentally we were and are anything but. None of us, given the current state of modern science, are some super-foetus grown in a test tube and all of us spent approximately 40 weeks in a uterus. In other words, all of us have a mother.

Pedro Almodóvar, Spanish director extraordinaire, has an impressive grasp of this concept. His 1999 film All About My Mother is, in a gorgeous swathe of melodrama and hue, a story almost uniquely of women and particularly of mothers. Created in a time where the post-Franco identity of the Spanish nation was still being somewhat refined, it was released to a fitting volume of international acclaim and is still held in high regard today.

A delight from the very beginning, as it commences enticingly with shots of medical equipment, it follows a fragment of Manuela’s life (played by Cecilia Roth) in the months following a certain, rainy night when her life was turned upside down. After a Madrid performance of A Streetcar Named Desire to which she has gone with her son Esteban (Eloy Azorín), Manuela watches on in horror as, in pursuit of an autograph, he is literally mown down by a passing car and killed. Understandably bereft, she does what any rational being would do in her situation: she runs away to Barcelona.

She returns here to confront a past abandoned almost exactly seventeen years previously, to find the father that Esteban never knew. The reconciliation of her past and present is, however, not something she achieves solely by herself. As time coalesces around her, she gathers a fascinating band of eclectic women: the ex-male and ex-prostitute Agrado (Antonia san Juan), pregnant nun Rosa (Pénélope Cruz), and actress Huma Rojo (Marisa Paredes). Together these women lend one another their mutual support and metaphoric shoulders whereupon tears are shed, realities accepted and lives re-launched.

If perchance in a hypothetical reality one were forced to describe this film in a word, a certain colour springs readily to mind. This, in the simplest terms possible, is a red film and one so alive that it very nearly has a pulse. Its characters and plot, almost tangible to their audience, are practically raised from their surroundings like cardboard cutouts, as distinct and unique as you and me. In fact in parts they’re almost most real than our own flesh and blood, for the chain of events that their melodramatic existence forces them to experience is just so stereotypically human. This animated investment of colour is a hallmark of Almodóvar’s cinema, especially in his earlier works, and is something that he has never ceased to employ. Red, in tone and metaphor, is infused in absolutely everything. It is the blood of the film itself as it courses throughout the narrative, throbbing as the plot unfolds.

Say that, even more hypothetically, we were then somehow obliged to provide an extra word to complement the previous. ‘Intertextual’, a word most likely loathed by anyone forced to mark high school English essays, here is appropriate. Every aspect of the film is saturated with intersections drawn between characters, settings and plot. Not only are Williams’ A Streetcar Named Desire and All About Eve (1950) fundamental to its inner workings, but a constant procession of allusions to transplants, plastic surgery and similar further reinforce this preoccupation. ‘Saturation’ is not to suggest that this particular facet of construction is in any way in excess; certainly the film practically groans under its referential weight, but never in an overbearing manner. Almodóvar retains complete control of his work at all times and despite a dense plot the film possesses a delicate air, an achievement indeed considering the circumstances.

Since the release of All About My Mother, Almodóvar has continued along the path of what appears to be a quest to create more films than any other human being alive. Age itself seems to pose no impediment and this prolific, seasoned Señor of more than 60 years has shown no sign of slowing down. Naturally, there is some substantial difference between his works and a degree of quality variation, but a similar high standard has consistently prevailed. The maturity and compositional supremacy that this youth from provincial Spain has built up over the years from cult film-maker to auteur extraordinaire is indeed a sight to behold. All About My Mother is a firm favourite among many Almodóvar lovers for many good reasons. One can only hope that his forthcoming The Skin I Live In (La Piel Que Habito) (2011) sustains this winning streak.