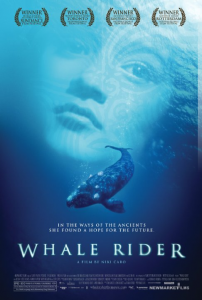

feminist film history 101: whale rider

In this new series, Lip writers take a look at a wide range of films to determine what it is that makes a great feminist film. From the black-and-white classics right up to the newest of new releases, this retrospective examines just what’s in the feminist film canon — and asks if anything needs to be added to it. To get the ball rolling, Emma Nobel makes the case for New Zealand’s own modern classic, Whale Rider.

Welcome to Feminist Film History 101.

Whale Rider is a 2002 film centred around Pai Apriana (Keisha Castle-Hughes), a spirited eleven-year-old born in tragic circumstances on the coastal village of Whangara. Pai’s story is one of strength: a coming-of-age tale about a neglected child who does the best she can to prove her worth, and to unify her desolate community.

Based on the novel by Witi Ihimaera, Whale Rider enjoyed a dream run at the Toronto International Film Festival, taking out the AGF People’s Choice Award and topping Bend It Like Beckham and Bowling for Columbine to become the firm crowd favourite. Its star, fourteen-year-old Keisha Castle-Hughes, is the youngest person ever to be nominated for an Academy Award in the category of Best Actress.

The crux of Whale Rider rests on Whangara’s 1000-year-old creation myth about Paikea, Pai’s ancestor and the founder of her community. Paikea is said to have saved himself from drowning in the sea by riding to shore on top of a whale. Since the days of Paikea, the male heir of the chief has inherited leadership of the tribe – but Pai’s father broke with the tradition by leaving his tight-knit family to follow his dreams, leaving her grandfather Koro and the Whangara community without a future.

It’s this hopelessness that Pai is born into, exacerbated when her mother dies in labour and her twin brother is stillborn. In a scene that shapes the rest of the film, casting a dark shadow over the tender moments later shared between Pai and her grandfather, Koro walks into the room where his deceased grandson and daughter-in-law lie alongside baby Pai and asks where his heir is. He doesn’t acknowledge the dead woman lying on the bed, or the quietly cooing baby.

‘There was no gladness when I was born. My twin brother died and took my mother with him. Everyone was waiting for the first born boy to lead us, but he died and I didn’t,’ Pai narrates. Her relationship with Koro is increasingly strained by her grandfather’s reluctance to set aside antiquated tribal traditions and recognise the potential that grows before him.

This is a man who can’t shake his reverence for the status quo; he loves Pai, but because of her gender she can never be his heir. Koro ignores signs of his granddaughter’s promise and devotion to him in favour of setting up a school for the local boys to find and train someone to succeed him.

Whale Rider is a quiet, considered critique of the patriarchal nature of families and societies. Pai’s story is a struggle for equality and identity as much as it is a story of empowerment, and Pai isn’t the only one who is challenging what’s expected of her. Koro’s first son, Pai’s father Porourangi, rejects the community’s expectation of him to become their leader, instead leaving the town to pursue a career as an artist. Whale Rider breaks the mould in more ways than one; in one poignant scene Porourangi tears up and is comforted by his daughter. It might not sound particularly novel – but try coming up with a handful of films where the lead actor is permitted to cry and not admonished for doing so, and you’re bound to come up short. I did.

Despite concerns with traditional tribal structures, Whale Rider is a universal coming-of-age story with the themes of identity, equality and belonging at its core. By itself the plot is fairly predictable, but stunning visuals and utterly incredible performances by the central Maori cast save the film’s heart. Director Niki Caro’s humble New Zealand offering delivers an honest, authentic account of a community where spirituality and tradition is at war with modernity and the decline of a generation – a confrontation that comes to a head through the eyes of Pai and her grandfather.