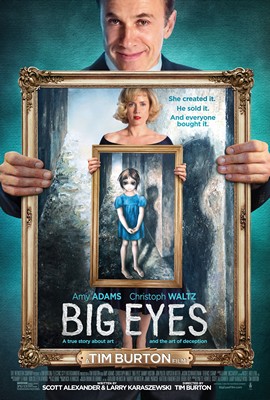

film review: big eyes

In recent years, director Tim Burton has made some truly appalling remakes; films filled with over-the-top CGI and best characterised as nonsensical insanity. His tired muses, Johnny Depp and (now ex-partner) Helena Bonham Carter, recycled zany character after zany character in lacklustre films like Alice in Wonderland (2010) and The Dark Shadows (2012), although the former did have the redeeming feature of being Mia Wasikowska’s breakout film. It seemed like these films were only being made for financial gain and were not the result of Burton’s artistic integrity.

Burton’s passions for bad art, the strange and the unusual have followed him his entire career, from his early days starting out with the quirky comedy Beetlejuice (1988) to the blockbuster Batman (1989) and its sequel Batman Returns (1992). His first encounter with Johnny Depp in the incredible Edward Scissorhands (1990) led to a lifelong friendship, the duo later creating masterful gothic pantomimes Sleepy Hollow (1999) and Sweeney Todd (2007).

But it’s Burton’s humanistic films that seem to have stood the test of time. His adaptation of the novel Big Fish (2003), which explored a strained father-son relationship, is a masterpiece of heart and humour. His exquisite and surprisingly heartbreaking film Ed Wood (1994) is a biopic about the worst director in history, Edward D. Wood, a man to whom Burton can no doubt relate. Ed Wood is arguably Burton’s masterpiece, so it’s only fitting that his latest film and return to form, Big Eyes, is a biopic also about some very big characters and some truly bad art.

Opening with the narration, ‘The ’50s were a great time, if you were a man’, Big Eyes is perhaps Burton’s most feminist film since The Corpse Bride (2005). In the late ’50s, Margaret (Amy Adams), an artist with a penchant for painting children with huge saucer-like eyes, leaves her suffocating husband with her young daughter Jane to live in San Francisco. Struggling to make money off her art, Margaret has a chance encounter with fellow artist, Walter Keane (Christoph Waltz). Walter is a charismatic, handsome, and struggling artist who paints Parisian street scenes, and he soon sweeps Margaret off her feet. When Margaret’s ex-husband threatens to take Jane away because single women don’t make “good mothers”, Walter proposes that they marry, and soon the couple are living together in domestic bliss.

Continuing their mutual struggle to make money off their art, Walter rents out wall space in a hip San Francisco club to sell the couple’s artworks. Surprisingly, it’s Margaret’s kitschy paintings that sell and Walter, in a fit of self-promotion, begins to pass them off as his own. It’s an absurd lie, but Margaret reluctantly goes along with it, feeling the guilt piling up on her as she is forced to lie to everyone she knows. Walter justifies his fabrication later by stating, ‘lady art doesn’t sell’; a sad but true fact of the time that perhaps is even still relevant now. With the “big eyes” paintings flying off the walls for ridiculous prices, Walters catapults into stardom whilst Margaret remains a recluse in her studio, struggling to keep up with the public demand, creating painting after painting, each one more whimsical than the last.

For all its absurdities, Big Eyes has a lot of heart and soul, mainly due to Adams’ performance and the importance of the story. In true Burton form, the film is also stunning to look at; drenched in retro nostalgia for the ’50s and ’60s, the saturated colours and quirky production design evoke the look of Edward Scissorhand’s conformist suburbia.

Adams is, as always, incredible as the meek and sympathetic Margaret. In a performance that earned her a Golden Globe, she’s subtle in bringing out Margaret’s long-suffering emotional state that bubbles under the surface of her stoic exterior. It’s a restrained performance that is in complete contrast to Waltz as the exuberant and twitchy Walter. The two-time Academy Award winner wastes no energy in depicting Walter as a selfish, self-confident and deranged man, who will stop at nothing to maintain the tangled web of lies he has created.

Explorations of ’60s counterculture, where everything bad was considered good and things would flit in and out of fashion in the blink of an eye, the film never questions why Margaret’s paintings are so popular: they just are. Perhaps they were popular because they simply appealed to so many people, and with the introduction of mass-produced prints, everyone could afford to have “art” in their living rooms. Set on the brink of the ’70s, with changes within the women’s liberation movement, Margaret isn’t your typical feminist character. She is presented as victim is many ways and of course we sympathise with her, but it’s her struggle to remove herself from Walter’s life and reveal the lie that is truly inspirational.

Big Eyes is a quiet little film, based on a fascinating absurd-but-true story; it’s easy to see why Burton would be drawn to such a tale. Both Adams and Waltz are perfectly cast in their roles and give performances that prove they are two of the greatest actors working today. With important messages about sexism in the art industry and critiquing the snobbery of art critics, it seems like the film is Burton’s revenge on all the critics who said his career was over. One thing is for sure, Big Eyes certainly proves them wrong.