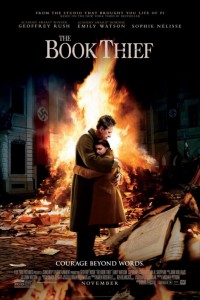

film review: the book thief

The Book Thief – to quote from the original novel, by Markus Zuzak – is ‘just a small story really, about, amongst other things: a girl, some words…some fanatical Germans…and quite a lot of thievery.’

On the eve of the Second World War, young Liesel Meminger (Sophie Nélisse) is sent to live with her new foster parents, Hans and Rosa Hubermann (Geoffrey Rush and Emily Watson) after her mother, a suspected communist, can no longer take care of her. When her younger brother dies, Liesel copes with her grief in a curious way: she starts stealing books. Although at first she does not know how to read, she learns from Hans, who reads with her from her pilfered volumes, and Max, the young Jewish man the Hubermanns keep hidden in their basement.

The Book Thief is an incredibly sad film. It is also a funny film, a beautifully composed film, a wittily scripted and excellently cast film. But when you make a film of a book about books – The Book Thief is adapted from the 2005 novel of the same name – you invite the question: what can a film do with a story that a book cannot do better?

Where the novel was fresh, quirky, even audacious in its approach to the subject matter, the film plays it safe: it favours happy endings and regurgitates the comforting myth of widespread resistance to the Nazis. The film paints Nazi officials as one-dimensional villains, the SS characters nothing more than coat racks for the uniform. They are unequivocally dangerous, ‘bad’ men who pop up in the story to hurt the ‘good’ characters.

The story strangely avoids thinking too much about the dangers of compliance and obedience; it is unwilling to portray morally questionable characters, or to accept that the participation of German people in activities like book burning helped to strengthen the Nazi position of dominance. The film’s only exception to this is Franz Deutscher – a schoolmate of Liesel’s and an enthusiastic supporter of the Nazi party, and an avatar for the risks of conformity – but he is a peripheral character, and one without nuance. He is painted as a thoroughly bad person, someone for the audience to hate and feel superior to, who is not even redeemed in death.

The idea that Nazi oppression emanated entirely from a centralised organisation has long been rejected by historians, but The Book Thief perpetuates the idea that Nazism was something that happened to the German people, rather than as a result of actions committed by them.

To risk a comparison of the novel and the film a second time, Zuzak’s story also loses something of its unconventionality as it makes the transition to the silver screen. The novel was narrated by Death, a perfect choice for a story set in Second World War Europe, who wryly describes himself in both book and film as being one of Hitler’s ‘hardest workers.’ Zuzak’s Death is not a thing to be feared, but an exhausted, overworked figure with a love for humanity. Director Brian Percival seems to have been reluctant to give Death a role as narrator, but pressure from fans of the book has lead to the inclusion a few of his lines. Subsequently, Roger Allam’s voiceover feels like an intrusion in the story, and a sarcastic one at that. Death, rather than seeming endearingly interested in Liesel’s story, seems callously disinterested in the rest of the film’s characters.

Although the fact that I read The Book Thief before I saw it meant a book vs. film debate was inevitable for me, there are elements in this story which are inextricably linked to the literary. It is, after all, a story centred on the pleasures and possibilities of reading, of the written word; something that is difficult to represent visually. When it comes to depicting the experience of reading, the filmmakers frequently resort to showing close-ups of the page, or panning slowly across the words Liesel writes in chalk on the walls of the family’s basement every time she learns a new one.

When Max falls ill, Liesel reads to him from stolen books; when the townspeople huddle, frightened, in a bomb shelter, Liesel tells them a story of her own devising to distract and comfort them. However, in both of these examples, the filmmakers edit out the part that presumably matters the most – the story itself. The audience sees and hears a string of disconnected sentences as Liesel reads Max The Invisible Man; we hear only fragments from Liesel’s improvised tale. When the filmmakers allow themselves to simply tell the story in their own medium, the performances, particularly those of Geoffrey Rush and Sophie Nélisse, are exceptionally strong, and Markus Zuzak’s novel provides excellent source material for a moving story. If you see this film, you will cry buckets, but the same can be said for those who will read the novel.

Every unread book is a new life waiting to be lived. As Liesel learns to read, she also learns to live: she questions how other people’s choice affect her life, she becomes more empathetic; she meets new people and forms new friendships. The Book Thief is a beautiful film, but it is an unnecessary one.