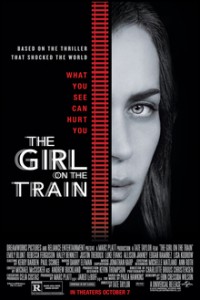

film review: the girl on the train

The Girl on the Train is violent, melodramatic and dark. Based on the insanely popular 2015 thriller novel by Paula Hawkins, the film sits within a new brand of female-led thrillers. These films typically have a women heavy cast and explore the white suburban ideal through some sort of mystery. Films and books like Gone Girl and The Girl on the Train sit somewhat uncomfortably on the cusp of feminism as they relish in a certain kind of revenge not fully explored in popular culture before.

The film starts with Rachel Watson (Emily Blunt) taking her daily train ride into the city. Rachel is an alcoholic whose life has broken apart since separating from her husband Tom (Justin Theroux), soon after learning she will not be able to conceive. Rachel has lost her job due to her drinking but persistently takes the train which passes by her former husband’s home, where he now lives with his new wife Anna (Rebecca Ferguson) and their baby. Whilst gazing out the window Rachel begins to watch another couple who live a few doors up from her husband. In this house live Megan (Haley Bennet) and Scott (Luke Evans), an apparently loving and sexed up perfect couple— who really need to close their blinds more (come on guys you live right next to a busy train line show some decency).

Rachel’s sad routine is halted one morning when she spots Megan, her symbol of perfection and all that she has lost, kissing another man. Rachel disembarks from the train and her point of view becomes stilted— as she drunkenly stumbles we hear screams and flashes of faces. Everything is confused, until Rachel wakes up covered in blood. Rachel then becomes a suspect for the disappearance of Megan.

My main interest in the film comes not from the fairly typical murder mystery plot that follows, but from the way in which the film creates exaggerated but still complex female characters. The film explores the psychological effects of male control with a feminist leaning. The strength and defiance of the women contributes to this angle, and the film’s big twist turns it into a story of abuse and survival.

Children and childlessness are also explored within the film. Rachel unravels when her idealised suburban life cannot be completed with a child. On the other hand, Megan’s husband aggressively wants her to have a kid but she wants an escape from what she calls the ‘baby factory’ of suburbia. In this film, babies as the traditional source of joy and family structure are instead a force which break up relationships, and so the film deviates from the traditional assumption that family equals stability and a happy ending.

Rachel, on the other hand, fetishises the “normal” stable family unit. She does this through a kind of female voyeurism for the suburban ideal. This is not something unique to this film (see again Gone Girl as well as Revolutionary Road), but it is much more literal with the very direct way this film focuses on Rachel’s gaze. Rachel’s face is often almost filling the camera lens. The dark patches around her eyes and her dry lips are seen in stark contrast to the pretty makeup filled faces of Anna and Megan. Rachel is a woman, but she is imperfect.

Part of the book and also the film’s appeal is Rachel’s ability to act out the fetish of revenge. Exploring dark female revenge has many feminist aspects because it affords power to women and gives them a chance and a space to get angry. However, in some cases it seems to just be a contemporary way to make women the femme fatale of cinema, as they become objects of fear and hate because of their “feminine” mystery.

There need to be more and better films like this. Films with a majority female cast. Films where the few male characters talk constantly about their wives. Films where women can be dark but still heroes that are not punished for going outside the norm, and where the fantasy of the suburban ideal is exposed. This film comes close and is greatly carried along by Emily Blunt’s gritty portal of Rachel, but it ultimately falls short because of its melodramatic nature which often tips over in blatant cheesiness.

Director Tate Taylor, who rose to fame with his also delightfully female heavy film The Help, has not done his best work here. The film’s symbolism is too obvious, as is the dialogue. Phrases in the film like ‘you made me do it’ are used like feminist window dressing alongside confronting depictions of violence. In such cases the violence becomes what is significant not the limply written, but far more important from a feminist perspective, words. The time shifts are also clunky, taking the form of a “six months earlier” style text which over simplifies what could have been a clever and complicated narration. The violence also gives the film a kind of Game of Thrones like excuse for the nudity. Ultimately, though, films need to tell more stories about male manipulation, and perhaps for now a popular film like this that makes such issues mainstream is good enough.