lip lit: hard to get

Apparently we’re at the cusp of the fourth wave of feminism, with formidable ladies like Amanda Palmer and Malala Yousafzai at the battle front. It’s all a bit tiring, really—to think that after an ocean of feminist thought, we have not yet toppled the old-age patriarchal values which restrict equality.

Unfortunately, it’s true: in many arenas, outdated ways of thinking still inform much of how we see the world. Including, dear reader, love and sex.

Like many other women, psychotherapist Leslie C Bell is disappointed that traditional paradigms of relationships and desire continue to exist, despite her patients existing in a society that is supposedly sexually liberated.

Specifically, she’s a little miffed that twenty-something women are faced with opposing cultural messages about relationships.

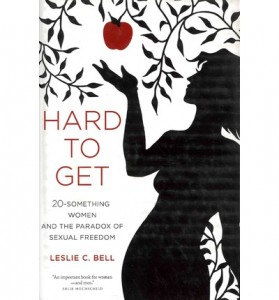

‘Possessed of greater opportunities than their grandmothers could have imagined,’ Bell writes in her book Hard to get: 20-something women and the paradox of sexual freedom, ‘Women find themselves confused, conflicted and uncertain about their goals in sex and love and how to achieve them.’

A chronicling of the intimate lives of women aged 24—28-years-old, the book weaves its way through the sexual development of different interviewees; all of whom are college-educated and childless. Some participants are heterosexual and homosexual, and some are women of colour while others are white.

Throughout the book, we see anecdotal evidence of a generation faced with endless contrasting expectations: can vulnerability be found in casual sexual encounters? Will men be discouraged if I know what I want? What will I have to sacrifice to have a long-term relationship?

Bell believes that many women encounter ‘splitting’: a ‘tendency to think in either/or patterns and to insist that one cannot feel two seemingly contradictory desires at once’. So we separate them into dual opposites: exciting sex or tender intimacy, career or relationship, good girl or bad girl.

Many of these ideas about women’s sexuality stem from the Madonna/Whore dichotomy, which typifies behaviour into two categories: gentle, loving, passive, against assertive, wild, and sexy.

Jayanthi felt suffocated by her parents’ expectations to be a ‘good girl’ until they found a suitable husband for her. In an effort to deviate from restrictive traditions she embraced a ‘bad girl’ identity, and engaged with casual hookups (some brilliant fun, some not).

This was her way of acting strong and independent without acquiescing to her parents’ demands. Ultimately, though, she reported feeling unfulfilled because her strategy of sexual activity was designed to avoid an emotional connection.

Similarly, Claudia, who grew up in a Mexican Catholic family, defined sex outside of a relationship as racy and exciting. In her mind, intercourse as a committed couple is only evocative of love and trust, and the way she perceives it she can have either one or the other.

Bell writes: ‘Claudia framed committed relationships as exclusive of ambition and adventurousness, so she cut them short.’ The 28-year-old with a PhD had decided to settle down with a man who loved her, but was remarkably unskilled in bed. The way she saw it, she couldn’t have both.

Historically, women were expected to focus on husbands and families without developing their careers. Now, in another example of splitting, our culture encourages this ‘new generation of highly educated women’ to focus on work aspirations, without much regard to developing a relationship until reaching their late twenties or early thirties. Interestingly, women who focus on a spouse before this time are, in some ways, looked down upon.

‘All the women I interviewed felt this encouragement [to follow their careers],’ writes Bell, ‘And many, like Katie, expressed shame at the desire to prioritise a relationship.’

These illustrations of the way ‘splitting’ is employed in our culture, which happen constantly throughout the book, can seem repetitive. But it almost needs to be to break through the subconscious assumptions we hold about sex and love. It was only after reading three-quarters of the book that I turned the spotlight onto the dualistic nature of my own thinking.

One of the most enjoyable things about Bell’s book is the exposure of real peoples’ inner sexual lives. If readers are anything like me, they will be heartened by the honest statements about confusion and desire, and relieved to hear that they are not so alone in their fears. The revelation of shared experience was a true joy.

Bell categorises her book and therefore her interviewees into three archetypes: the Sexual Woman, the Relational Woman, and the Desiring Woman. Although this works in the structure by supporting a developing theory, I felt as if the writer was forcing square pegs into round holes in her interviewee classification.

Bell’s conclusion demonstrates great vision for a way forward. She suggests that to heal young women’s ideas about desire, we must commit to better sex education, and a more complex representation of women and their sex lives in pop culture (hands up if you’re bored of the paltry one-dimensional women in rom-coms. How do they still exist?) And of course, we must be more open with our girlfriends about the great contradictions of our intimate lives.

Our feminist foremothers fought for our empowerment. And what does that mean? Making informed choices and pursuing our greatest desires.

‘Getting what we want from sex and relationships,’ Bell writes, ‘requires accepting and tolerating seemingly contradictory parts of ourselves…if we can develop curiosity about our desires and aspects of ourselves that don’t match up with those sanctioned by our culture, we may begin to build lives in which we feel more pleasure and satisfaction.’

Got a spare minute? Why not fill out the Lip reader survey, for your chance to win a free copy of issue 23 + an awesome Lip tote bag? We’d love to hear your thoughts!