lip lit: sydney writers’ festival—’ferrante fever’

This is a review of a session held at the 2016 Sydney Writers’ Festival.

*

What is it that we find so fascinating about a reclusive novelist? There are plenty of writers who have attempted anonymity, with varying degrees of success: Harper Lee and Thomas Pynchon both spring to mind. These authors have chosen to stay out of – or been chased out of – the spotlight. Authors at the other end of the scale, like JK Rowling, might secretly yearn for namelessness, but when they openly engage in and try and dictate interpretation of their work, readers might wish they’d stayed in their hermitages. Some superfans might want to know everything there is to know about an author, but too much knowledge can get in the way when it comes to the reading of a novel.

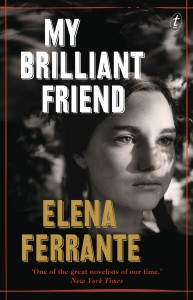

This is why Italian novelist and international sensation Elena Ferrante decided, before she had even published her first novel, on total anonymity. She gives select interviews via email, and her work – most notably the blockbuster tetralogy known as ‘The Neapolitan Novels’, along with other works dating back to 1992 – are the only thing up for discussion. And this is why, at the Sydney Writers’ Festival event ‘Ferrante Fever: A Celebration of Elena Ferrante’s Novels,’ there was no author present.

Instead, Ferrante’s English translator, The New Yorker’s Ann Goldstein took her seat on a panel made up of Australian readers of her work: Lateline journalist Emma Alberici, writer Drusilla Modjeska, and memoirist/screenwriter Benjamin Law. Goldstein was the only international guest and the only one present to have had a direct hand in the Ferrante phenomenon.

Sydney Morning Herald literary editor Susan Wyndham led this assortment of panellists through a series of by-the-numbers questions, largely focussing on what it was about the novels that had inspired such feverish appreciation. Law and Modjeska were both in enthusiastic agreement that it was a combination of the novels’ television-like structure – cliffhanger endings and short, potent chapters – and the female friendship at the centre of the series that made Ferrante’s writing so addictive. Alberici seemed to admire the novels for different reasons than the other panellists, finding appeal in their commentary on the political and social structure of Italy in the 20th century.

When Wyndham asked the question, ‘Are these novels feminist?’ the answer was a unanimous and unequivocal yes from the panel – with murmur of assent from the crowd. For the Neapolitan Novels are explicitly feminist works. In contrast to Ferrante’s earlier novellas, Goldstein and Modjeska observed, which were commonly shorter pieces written from ‘the middle of intense experiences’, the Neapolitan Novels have an enormous scope, and a correspondingly large cast of characters. The series takes on modern history and reasserts womn’s role in shaping it, tackling themes like violence, second-wave feminism, class struggle, and the oppressive nature of motherhood within a patriarchal society. The novels’ far-reaching themes are woven together by the friendship between narrator Lenu and her childhood companion, Lila.

Ferrante’s candid portrayal of female friendship is at the heart of why the Neapolitan novels are so popular – on this, the panel was once again in agreement. As Law pointed out, this friendship is not always healthy, or positive, and it certainly isn’t romanticised. Ferrante’s depiction of the friendship of the two women is unflinching, but it stands out as a novel that allows women to be real women: complex, contradictory, angry, bitter, unfaithful, vengeful, cruel, cold, passionate, even crazy – everything, in short, that we are socialised not to be.

With such a raw, painfully honest portrait of womanhood, it is perhaps no surprise that Ferrante retreated from the public eye before it had a chance to turn on her. Goldstein, who translated the novels into English as she was reading them, described the experience as like being inside the narrator’s head. She understood her motivations so well that she could not but sympathise with her. But there is something dangerous about that level of brutal honesty that makes Ferrante’s decision to stay in the shadows just as sympathetic.