Lip Verse: The Argument

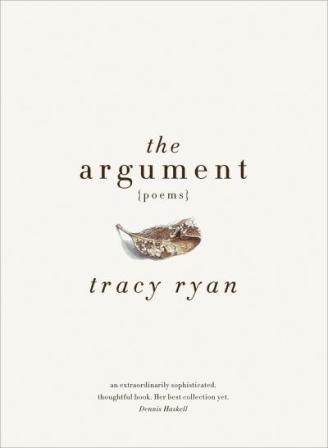

Tracy Ryan’s The Argument is a profoundly thoughtful and sensitive volume of poems. It won the 2011 Western Australian Premier’s Book Award for Poetry, which was announced in September last year, and it is the poet’s sixth collection.

More than anything, it’s the domesticity that appeals to me about this book. The poems often point to ordinary, everyday details that wouldn’t normally be considered poetic—from mouldy fruit to falling over in the car park. Women’s work is frequently a backdrop to the poems—from cleaning cobwebs and scrubbing the kitchen, to bearing children and tending to them. Ryan has spoken previously about the way language takes on a feminism function in her work:

…my writing is inextricably bound up with my feminism. This would be the only real connector between my books. I am interested in trying to find ways in which language may be interrupted, disrupted and rejigged for feminist purposes (among others). Usually this attempt would arise from something in either my personal life or the world around me (2001).

A great example is The School Run, in which Ryan subtly notes the rarity of seeing a man in the daily ritual of taking the kids to and from school:

… A ready nod

or smile for the odd dad, doing his bit, but by and large

a loose-knit team: the same, the same.

Such simple, honest observations (rather than overt political statements) are what makes Ryan’s feminism, and indeed her poetry, so powerful.

Ryan engages all the senses when writing about her experience of living in the wheatbelt of Western Australia—the farmers, the harvest, the freight trains, and even the bounties of her vegetable garden (broad beans and roma tomatoes). She then moves from the heat of Australia to the icy cold of American winter amid power failure and natural disaster—‘Narnia after the witch’. Enigmatic creatures, too, flit or patter through the pages; Ryan writes of owls and, delightfully, deer:

The velvet approach:

nights I would never hear them

could only tell

there’d been a visitation

next morning: prints in snow

at my study window.

One of my favourite pieces in this collection is Poem Written With the Left Hand. It is an unexpected exploration of empathy for the less-coordinated companion to her dominant right hand. Ryan describes her left hand as the ‘understudy’ and ‘always the bridesmaid’. As bizarre as it may sound, my heart went out to this poor hand struggling to write a poem:

you pause & ache but will pick up,

persistent as a six-year-old

self left out, sat in cinder-ridden

longings, lurch in image for what I was

reading back then, all that pride of impression

but you could not compete

But the poems that went further—that is, took my heart and wrenched it in two—were Persistence and Sound Effects. Both of these address the loss of the poet’s brother, whom we gather from the book died tragically when he and Ryan were only teenagers. In Persistence, Ryan describes combing her brother’s room after he died:

The built-in robe was full of schoolwork

which I read, word by word, over a week,

curled in his bed, trying to find one concrete, personal

aberration, digression, cartoon, doodle

or love-note, anything not generic, anything

giving out his spark.

She describes how his room smelt of sweat, twice-worn shirts and odd socks—‘the scent I knew would not endure’. In the same poem, the poet visits the cemetery and notices the names on a nearby headstone:

So it seems your dead and mine

are close neighbours, having between them

filled in that space I mentally

marked for myself before I forgot

the fight, and went on living.Two boys of the same last name, I imagine

brothers, I imagine the same blade ravaging

your family, the same laceration

in the same soft earth, the laying-down.

Already in place when our turn came.

In Sound Effects, the poet’s son is engaged in imaginative play, narrating his superhero actions and making the sound of an ambulance siren. This reminds Ryan of her own childhood, when she and her brother used to record sound effects and voice-overs onto cassette tapes:

… Nee-nah nee-nah

and the needle jumpsover thirty years

to our own games.

Memory opens – accordion fileor a lung that had collapsed

without my noticing

so I went on breathingwith what was left. And now this

selection of noises, our old cacophony

my constant tinnitus.

The book is achingly moving. It contemplates the mysteries of death and birth, but ends with a humble meditation on love—suggesting, perhaps, that finally, this must be humanity’s comfort. One Flesh describes the familiarity and acceptance that evolves and deepens in long-term intimate relationships:

… Pattern

we have wilfully become, where

nothing provokes disgust, neither

a shirt sniffed at to determinewhether it will pass one more day

because the wash didn’t get done

nor my toothbrush fallen back on

if yours is somehow thrown away

Ultimately, The Argument is hauntingly beautiful. And although the title references humanity’s ‘argument with death’, I felt the collection was rather ‘a long conversation / only the smashed syntax of a poem might sustain’—a conversation that is very much about life.

The Argument is published by Fremantle Press.

Bronwyn Lovell is an emerging poet living in Melbourne. Her poetry has been published in Antipodes, Cordite Poetry Review and the Global Poetry Anthology. She was shortlisted for the 2011 Montreal International Poetry Prize.