magdalen laundries for “sluts” in “moral danger”: why I founded ‘Found Festival’

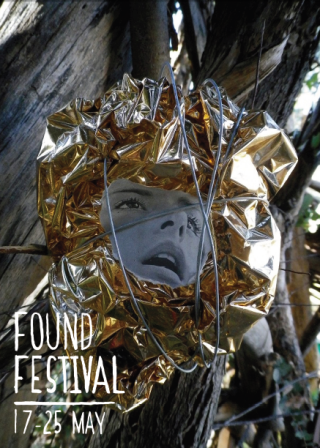

I have been quietly and frantically working away on the Found Festival for almost two years now. It is an arts event taking place from 17–25 of May at The Abbotsford Convent featuring 100+ women – artists, performers, producers, speakers, musicians, choir members, meditation experts and everything in between and around those limited definitions.

I began crafting Found after discovering in the previous life of The Abbotsford Convent that it once hosted a Magdalen Laundry. Magdalen Laundries were institutions run by nuns to incarcerate women who were deemed to be in “moral danger”. These women were often referred to as ‘lost and wayward,’ which is the polite old timey way of saying they were “sluts”. They were forced to abandon their lives and families (more often than not their families were the ones who sent them away), to perform menial labour, and as the term Laundries suggests, most often to work ceaselessly as laundresses, unpaid.

The first laundry was opened in 1758, and the last shut in Ireland, staggeringly, in 1996. Just think about that for a second here: that in our supposedly democratic, fair and just Western societies, you could still be imprisoned in 1996, without trial, for acting against the wishes of a Church that supposedly has no power over the government because of private sexual activity. It is not staggering because this sort of human cruelty is unfathomable – we live in a world that still discriminates, humiliates, tortures, murders and enslaves millions daily; a world where you can still be executed for being gay or for kissing a man who is not your husband.

What is staggering to me is the false moral high ground that is brandished to justify racist Western attitudes to other cultures, whose social systems are painted as far crueller and less refined than our own. Yet here we are as late as 1996, punishing women for sexual activity by way of cruel humiliation and gruelling slave labour.

The unequal spotlight that the West most often turns on everyone but ourselves in order to project this false sense of superiority creates a false reality. Even at the lowest estimate the Laundries held captive at least half a million women. Some of them were held during my lifetime.

Yet, I had never heard mention of these women or their stories.

So I created the Found Festival, in order to shed light on this history, because I am interested in the way societies continually ‘build over’ things that are painful in order to supposedly move on and forget the memories these places hold. Yet, who is it that gets to decide such things? Not generally those who were affected directly by the circumstances. So for whom does this bulldozing of the true, lived experience of individuals really serve?

Feeling forced to keep your personal pain a secret in order to make others feel more comfortable in your presence is known to be one of the most painful aspects of living through a psychologically or physically violent trauma – it deepens a sense of alienation and creates the painful need to continually monitor your thoughts and behaviour.

When we allow historical traumas to become and stay hidden, we are complicit in the social structures that allow institutions like the Laundries to not only form, but to flourish. In fact, we are watching it happen now before our very eyes in the form of the Manus Island Detention Centre. It makes me depressed to see history repeat itself dumbly, over and over again.

Once I had stood in the Magdalen Laundry space, which remains in an untouched condition, and felt the weight of its history, I knew that I had to create something that drew attention to this space.

This was, however, much easier said than done. Deciding on the best form the experience of this history should take was an incredibly difficult and painstaking process, and I am still not sure I have it right. I was concerned that what I was doing would be seen as co-opting a cause unrelated to my own lived experience for personal gain. Or that it would be, at best, another token gesture and, at worst, another example of culturally elitist forms taking historical oppression out of context, using its legitimacy to generate the meaning it fundamentally lacks. In my darkest hours I thought such things, and doubts still plague me about my motivation, my approach to inclusivity and the way I phrase my politics.

But I began to realise that if I didn’t have and express these doubts as a part of the process of delivering this program, then I was probably not thinking deeply enough about the issues that it raised. My anxiety has become a marker of (in the very least) my thoughtful approach to the complicated questions the Magdalen Laundries raise in being used as an arts space. At the end of the day I decided that it is better to create experiences that approach, tackle or shed light on these questions, rather than to simply ignore them because they were too hard to answer.

This belief particularly spurned me on as I knew it was this same attitude of ‘it’s too hard’ that pushed the Magdalen Laundries to such wild success. It was ‘too hard’ for a society to deal with a woman who had a child out of wedlock, or was precocious and wilful, or raped, or any manner of things women were expected not to be in a world that recognised their basic function as providing housekeeping and children to the man who legally owned her. It was too difficult to devise a way to deal with these women who did not do what they were told, and thus were banished to the fringe of society, behind a stack of sheets and shirts where they would be too exhausted and confined to ever make trouble again.

The use of such institutions as a fear tactic wielded in order to deter other would be dissenters (see again: Manus Island) really struck me. I came to understand that a great part of the private anxiety I was feeling about creating Found was based on a learned self loathing that urged me not to speak out, not to “rock the boat”. I was afraid of being labelled as ‘one of those crazy Feminists’ by the oppressive “privileged white guy” narrator to my fears, who does not like you to think and feel about such things as oppression, or the inequality of wealth or gender-based violence. I know that a great deal of my fear of judgement was expertly crafted by the legacy of institutions such as The Magdalen Laundry.

In 2013, the Irish Government, who was known to have the most active and brutal laundries, finally admitted its collusion with the church in order to remove these women and children from their lives in exchange for lucrative trade deals hinged on the free labour they would perform.

These messages continue to reverberate between the ears of every woman on the planet, who each in their own way stores such messages in their Fear Bank, which emits unasked for anxious messages such as ‘make sure you act like a lady or you will be punished.’ Or perhaps the omnipresent, ‘you deserved it, look at the way you were dressed.’

Well obviously in light of all the epiphanies, onwards I went.

During the course of putting together this program, I have been privileged to have shared the most fascinating, raw and personal conversations with countless women; these women who understood my nervousness completely and shared my fears regarding the label of feminist political activist being potentially damaging to a career or personal life. They understood this was stepping over a line into territory that was dangerous to a woman’s future. When you have strong convictions and pride of self, but have been conditioned so intensely to consider yourself lesser, the hurt is vast.

These women felt disheartened mostly because they knew they that any attempt to talk about gender-based inequality would immediately be derided or crushed by precisely those who had everything to gain from this inequality, and nothing to lose. They understood that each time they attempted this and got nowhere, that is was another small blow in the thousands of small blows that eventually weigh a person down. I listened to a lot of fatigue and a lot of frustration at feeling as though their voices were falling on deaf ears.

The more and more I spoke with numerous women (and men) about these issues that were being raised, the bigger Found grew, until it became the Festival-sized program it is now. To share yourself and your work on a public cultural platform is an incredibly difficult, yet ultimately triumphant act. It is an ultimate power most often rewarded to men, often regardless of ability.

It is this transformative experience – the sense of self-validation that comes from seeing yourself represented through culturally significant forms – that is one of the realest and most privileged aspects of men’s current political and social position on this planet.

I wanted to provide more women a taste of this sense of collective pride. I wanted us to sit around and simply talk openly about sex and politics and ourselves on the very ground where these women were imprisoned. This is why I call Found an ‘act of positive protest.’ We are thumbing our nose at our history; we are combating systemic hatred by coming together to share a laugh, to dance, to be renegades simply by rocking up and being our unabashed selves. Our approach is crafted specifically to be welcoming and unaggressive – it is about conversation rather than lecturing. It is an experiment in the healing power of joy, for adults who are trapped in a world that pushes them to shut up, stop thinking and get back to work.

Our society as a whole is not yet at a place where the general public is politically or spiritually conscious enough for nuanced argument about ingrained misogyny. Perhaps it never will be.

So Found works around that problem, while still making it clear that we are loud and proud; that we are not simply a “problem” that can be made to go away.

You have tried your best, and you did not succeed in making us disappear – so get used to it.

Lip is proud to support the Found Festival, which takes place at Melbourne’s Abbotsford Convent from May 17 – 25, 2014. For more information about the festival, check them out online at www.foundinitiative.com and ‘like’ them on Facebook here: https://www.facebook.com/FoundFestival

Bravo Audrey and grateful for your obvious passion,vision and skill. I wish I could be in Melbourne to attend.