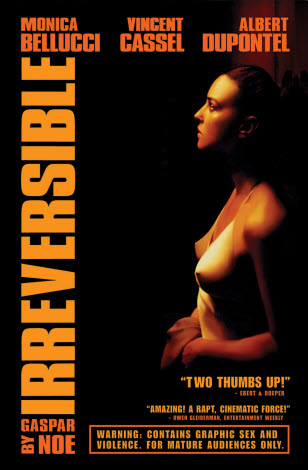

celluloid relapse: noé’s irréversible

Murder, as a cinematic experience, is something to which the film watching collective no longer particularly objects to. Snuff films aside, today on-screen murder orchestrated to varying degrees of gore and sadism is tolerated, even enjoyed. It excites, thrills and grants access to an activity that the majority of society will hopefully never engage with, adding a whole new meaning to the idea of vicarious living. The likes of James Bond, horror films and heck, even sappy romances like The Notebook (2004), would be an entirely different experience without murder or at least the looming threat of death. Indeed, in the case of The Notebook, the inclusion of a murder plot or pretext would have contributed much to the quality of the film and to the audience’s ability to tolerate it.

Murder, as a cinematic experience, is something to which the film watching collective no longer particularly objects to. Snuff films aside, today on-screen murder orchestrated to varying degrees of gore and sadism is tolerated, even enjoyed. It excites, thrills and grants access to an activity that the majority of society will hopefully never engage with, adding a whole new meaning to the idea of vicarious living. The likes of James Bond, horror films and heck, even sappy romances like The Notebook (2004), would be an entirely different experience without murder or at least the looming threat of death. Indeed, in the case of The Notebook, the inclusion of a murder plot or pretext would have contributed much to the quality of the film and to the audience’s ability to tolerate it.

Such a forceful removal of life is, for some, the epitome of sin and wrongdoing ever contemplated. It can however be argued that physical and emotional torture, the pain from which remains with the mind and body long after their conclusion, is significantly worse. Perhaps it is due to such prospects of a life subsequently disfigured that rape features far less in films than its life-taking counterpart. Rape – particularly of females – is seldom portrayed on screen, and thankfully so. Seldom is it enjoyable to witness.

Irréversible’s (2002) seemingly interminable rape scene is simultaneously one of the most awful and most spellbinding moments that film can ever possibly know. As the viewer, one feels the pain, the humiliation and the abject torture inflicted upon Alex (Monica Belluci), victim of the wily caprices of time, fate and the absolute disregard for the dignity of one human being by another. This is an incredible moment, but only in the sense of its realism and technical composition. Perfectly composed and executed, it envelops the viewer who does not just feel what Alex feels, but lives it too.

It would normally be wise to enlighten the reader as to how it was that Alex’s existence could so forcefully mutate under the grasp of her rapist (Jo Prestia), and how previous, arbitrary interactions with her boyfriend Marcus (Vincent Cassel) and friend Pierre (Albert Dupontel) could have lead to such a deed. To do so would unfortunately spoil the film. Knowing the least about Irréversible as possible is honestly the best approach one could possibly choose. Reading anything about it (including its IMDb summary) will ruin the surprise of the film’s best features.

Almódovar, king of colour and melodrama, manages to solicit a completely different reaction to rape than Noé. In his film, Kika (1993), his equally drawn out rape scene is surprisingly comical. Premise, situation, dialogue and a novel use of mandarin segments somehow coalesce to form a light hearted and hilarious treatment of such a sensitive topic. Almodóvar treats this sequence with the same ambivalence and aesthetic attention normally afforded to murder. This is a gorgeous scene – much to the horror of the viewer. It is hard to know what he is trying to say here, if indeed he wants to say anything at all. This is not a parody of rape, and nor is it satirical. It almost appears to be a relatively empty statement of fact, perhaps to force its audience through such exposure to accept what is unfortunately a daily occurrence for many women everywhere in the world. This is, of course, pure speculation

It remains to be said that a lack of rape portrayals in the fabulous alternate reality of cinema is possibly best left as is. Unlike celluloid murder which, if portrayed well, can be quite perversely poetic, the representation of rape as a glamorous or beautiful process should just never come to be. Irréversible’s rendition thereof is of course anything but aesthetically pleasing, and after having had seen it, one will most likely never wish to watch it again. Despite this, it is an incredible moment in an incredible film. From our perspective from our bourgeois cocoons, rape is for many a fact that was surrendered long ago to the realm of indifference. Irréversible, and the prolonged torture it portrays, are a shock back into reality and just what the doctor ordered.