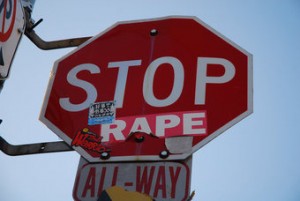

ponytails and perverts: is it wrong to give anti-assault advice?

Young vulnerable women are sometimes told that we shouldn’t have our hair tied back in a ponytail in public. Not for any aesthetic purpose, but for safety reasons. If a man – it’s always the threat of a shadowy man looming over you – wants to assault you, you will make it so much easier for him if you have a ponytail which he can conveniently grab to control you.

Is it reasonable to dispense this advice? It’s certainly not disseminated maliciously in an attempt to restrict our freedoms. It is always with the best of intentions, but that doesn’t mean it’s entirely on the mark.

Telling women what we need to know to protect ourselves is important. It’s girl power. Small measures like not putting down your drink and always telling a friend where you’re going can make all the difference to your safety. These tips are effective and do not restrict our freedom of expression – and in this way, they differ from being told not to tie your hair up.

Anti-assault measures can be likened to shutting your front door so you don’t get burgled. In utopia, such a measure would not be necessary, but in the imperfect society we live in you’d be a fool to leave your door wide open when nobody’s home. But there is an essential difference between your house and your body.

Your house can’t put up a fight or deny consent, but your body can. You are guarding your own body all the time. So the house analogy is more like leaving your door open when you’re at home – which plenty of people do without getting robbed. If someone tries to come in and take your things, you can shoo them off. By virtue of occupying your body, you are able to defend it if need be.

That’s not to say that there is no place for anti-assault tips. Guarding your drink closely is a good one to follow. But the way you would deal with having your drink spiked is entirely different to what you would do if an attacker grabbed you by the hair. Drink spiking is insidious; you don’t know what has happened until it is too late. But when you are aware that you are being assaulted, as you would be because of the pain of having your hair pulled, you are able to defend yourself.

Despite the good intentions, there is an anti-feminist, victim-blaming element about being advised not to wear ponytails in public. By placing the onus on the woman to style her hair so that it is harder to pull, in the event she is assaulted it becomes her own fault for not taking that extra precaution. It’s similar to the idea of not showing off too much skin – something you’re instructed to do to supposedly reduce your risk of being sexually assaulted.

Another piece of anti-rape advice, that has victim blaming down to a tee, is to not wear loose clothing so your attacker has nothing to grab onto. The stupidest part of this advice is that even if a woman follows it, if she is assaulted it can still be said that it was because she has failed to take the right precautions. Wearing tight clothing, so potential attackers cannot grab hold of her as easily, means you could argue that she is dressing provocatively. Once again, what happens to her becomes her own fault.

On a more practical note, there is something useless about the advice to not wear your hair up or wear loose clothes. If you are physically strong, you should be able to fight off your attacker whether he is gripping your hair and clothes or not. Conversely, for a small and physically weak woman like myself, having my hair in a less grab-able configuration will not help much in the case of an attacker. It would be more useful to give women tips to actively defend themselves, such as where to hit an attacker in order to inflict the most pain.

Ultimately, the more restrictive of anti-assault tips create more problems than they solve. While they are well intentioned, there is a lack of evidence to suggest they make a difference. You never hear anything more than sparse anecdotal evidence that it’s easier to assault a woman with a ponytail.

By placing the onus on women to resort to ludicrous measures like changing our hairstyles, they are adding to the culture of victim-blaming. There comes a point at which anti-assault tips are no longer about girl power. They are taking the power away from girls by making us scared of what’s out there, by binding us with silly rules about what not to wear, and by blaming us for not doing enough to avoid being assaulted.

By Natasha Abrahams

I started reading this article thinking “telling a woman not to tie her hair back to reduce assault risk? Ludicrous! Do people really say that? I’ve never heard such a thing!”. Which made it all the more obvious that telling a woman not to wear tight clothing is also ludicrous. Well written!

“Your house can’t put up a fight or deny consent, but your body can. You are guarding your own body all the time. So the house analogy is more like leaving your door open when you’re at home – which plenty of people do without getting robbed. If someone tries to come in and take your things, you can shoo them off. By virtue of occupying your body, you are able to defend it if need be.” – This notion that you are always “guarding your body” is problematic – if you walk through a park late at night on your own, are you “guarding” your body as well as if you were in a crowded place? Furthermore, the notion that you can “shoo” someone off if they walk in ignores the fact that many people are killed by panicking thieves who are caught mid-act, maybe not so much in Australia, but definitely in other countries around the world.

I think it’s important, however, to emphasise the subtle, yet important, distinction between the idea of putting yourself at greater risk and “victim-blaming”. If someone leaves their front door unlocked all the time and thieves walk in and steal everything, the thieves are just as culpable for the crime as if they had robbed a well guarded house. People may make the distinction that leaving the door unlocked made it easier for the thieves to enter, but, in the eyes of the law, and in a philosophical sense, this does not equate to it being the victim’s “fault” that they were robbed – the agency of the perpetrator is not diminished. Similarly, when a bank accidentally deposits huge sums of money in the wrong bank account, we don’t let the receiver keep the money simply because it was the bank’s fault. While this distinction re: greater risk vs victim blaming may not be prevalent in contemporary discourse on sexual – or any – assault it does not mean it is not valid.

I’m surprised they haven’t told short women to grow taller because being short means an attacker can pick you up easier and carry you off into the bushes or their car to attack you.

What a load of bloody rot.

I’m so sick and tired of “men” coming up with ways for women to “protect” themselves.

There are ways to protect and that’s to take a few self defence classes and learn how to rip a man’s dick off or shove your fingers in his eyes, kinda like with sharks. Women do need to protect themselves but when we have the “police” telling us to basically lay there and be raped so it saves you from being killed, I just want to kill every bastard on this planet.

“when we have the “police” telling us to basically lay there and be raped so it saves you from being killed” – wow which police officer said that?

I once asked two police officers what to do to avoid/protect yourself if being attacked- they said “Don’t walk alone” and “Run!”. That sounded like fair advice. Not everyone is telling girls not to wear ponytails! (or to not struggle while being raped).

Just thought we should see the whole, balanced picture.