universities, sexual assault and the trouble with “bad apples”

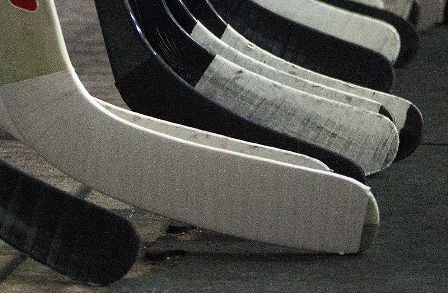

Late last month, police in Thunder Bay, a small city in northwestern Ontario, Canada charged two students from the University of Ottawa hockey team with sexual assault. Both men, David Foucher, 25, and Guillaume Donovan, 24, were in Thunder Bay for an away game against Lakehead University when they allegedly assaulted a 21-year-old woman. The circumstances of the allegations against (until now) unknown players have been disturbing: Réal Paiement, the team’s head coach, knew about the assault and said nothing to the senior administrators. He has since been let go.

Since finding out about the alleged assault, the U of O has acted swiftly and the conversation regarding punishment has been fairly quiet. Of course someone should answer for the crime and a real investigation should be carried out. What hasn’t been quite so unanimous is the decision by the university to suspend the team for the rest of the 2014-15 season, even now after two men have been charged.

The decision to punish the entire team is what has divided even casual observers of the story. The university says that they aren’t being suspended for the alleged crime; they are being suspended for the events leading up to it – reportedly a party involving alcohol. If that’s the case, this decision isn’t unusual; my own university’s hockey team was suspended for drinking last year, albeit for only seven days.

While the players, their parents and their supporters might feel they’ve been unfairly penalised for the actions of two, the loss of a single school’s hockey team for a single season means very little. College sports – even hockey – don’t mean as much to Canadians as, say, post-secondary football in the United States. High school and college athletes in this country aren’t shown the same deference that inspires a show like Friday Night Lights.

However, many believe the team is being penalised for what happened in Thunder Bay. No matter the aspirations of the players, the suggestion that even those who weren’t involved should miss out on an entire academic year of ice time seems deeply unfair, no matter who was at the party or who might’ve known about an assault. The team is considering filing a defamation suit against the university.

This case has stood out in Canadian media, partially because the concern about rape on campus has grown over the last few years. Stories about sexual assault, rape and rape culture are appearing in the news with alarming frequency, including stories of people working to minimise the problem – even cover up the crimes. Not that Canucks had any illusions about the pervasiveness of rape before (though there are many, of course, who will stubbornly refute this) but universities are still held to a higher standard of enforcing right and wrong, of fostering respect for the rules. Naïve? Sure. But still reasonable.

Cases like Steubenville and Penn State; the systemic covering up of sexual assault in the U.S. military; the appalling story of a woman allegedly assaulted by police in France; the decades of assault on children in the Catholic Church seemed exceptional – and were, in their own way. Despite the long and complicated struggle to address sexism and sexual violence in the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), the thought of any institution keeping sexual assault quiet is disturbing. It’s another example of rape culture protecting men, of concerning itself with the futures of young men despite the very real consequences to young women. Of course we should take allegations of sexual assault seriously, yet there is a tendency to wonder about the impact on the accused – and their cohort – while shifting the blame to the victim. (One of the battle cries of the Men’s Rights Movement after all is that women lie about rape and destroy the reputations of men.)

Universities have a monetary incentive to both ignore sexual assault on campus and also take a hard stance against it. Theoretically, the ivory tower exists to shape the attitudes and minds of the next generation of voters, policymakers, lawyers and healthcare professionals. Therefore it has a responsibility to the public to act when students are accused of behaviour that offends the greater culture. Though it might feel like it sometimes, college campuses do not exist separate from the rest of society. But universities are also businesses, and like any good business they go to great lengths to protect their image. Consider York University’s libel suit against Toronto Life after the magazine wrote about that school’s own problems with sexual assault or the many, many examples in Caitlin Flanagan’s exhaustive feature in The Atlantic, “The Dark Power of Fraternities”. A school that develops a reputation for being unsafe or hostile attracts fewer freshmen, less funding and investment, and fewer donations from alumni.

The University of Ottawa is taking the right step. Too often a victim of sexual assault must come up against not only their attacker and an apathetic justice and legal system but the judgments and shame of their communities as well. This is made even harder when their attacker is part of an institution with power, resources and incentive to stand behind one of their own. When people talk about only a few “bad apples” in this or any other case, they ignore the fact that those apples are raised in a culture that promotes their behaviour and so rarely stands behind women who are assaulted.

It’s unfortunate that so many are spending what might be their last university season off the ice, that they have been connected with a criminal investigation. It’s even more unfortunate that so many assaults go unreported out of fear.