twitter is the world’s panic room – and that’s okay

Before Twitter was as omnipresent as it is now, the concept was regular fodder for the writing of op-ed columnists. Experts, journalists and technophobes started philosophising about what this latest social networking site meant for privacy, intimacy, and communication. Globe and Mail writer Ian Brown even theorised that Twitter’s appeal had something to do with our fear of death.

‘The lure of Twitter is the lure of Right now,’ he wrote in a 2009 article titled, ‘Give me Twitter or give me death’.

‘There is no death in the moment of Right Now. There is only where/what/why/who I am. If you are tweeting or tweeted, you are not dead yet.’

Of course, that was four years ago. Millions of users later (including celebrities, corporations and early skeptics), the ubiquity of Twitter has brought with it a new set of anxieties and significance.

We’re still trying to figure it out.

The social network might have drawn in the neurotic death-fearing types in its infancy, but it is now much closer to what New York Times contributor Peggy Orenstein suggested a year after Brown. Twitter, she argued, is less about declaring existence and more about the performance of life; it is carefully managed for all who watch (I imagine the sight of dwindling followers is similar to a director watching her audience rise up and leave in the middle of a show).

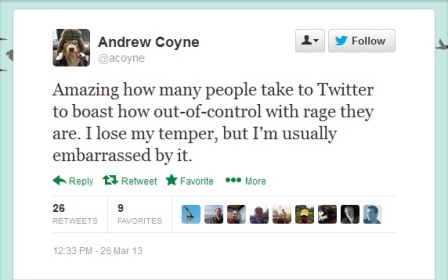

Consider then the complaints of well-respected Canadian journalist Andrew Coyne, who rightly observed that a ‘crisis’ always seems to be happening on Twitter. The ‘collective meltdowns’ he said, seem to come often.

‘Amazing how many people take to twitter to boast how out of control with rage they are,’ he wrote after an article in Maclean’s by Barbara Amiel dismissed the rape of Steubenville’s Jane Doe as a consequence of an ‘anything goes sexual society’.

‘Somebody writes something you don’t like, shrug, scratch your head in puzzlement, work through why it’s wrong. But save the moral preening,’ he added.

There are some problems with these arguments.

For one, the crises on Twitter are rarely spontaneous. Global crises spill onto Twitter as its users process every scandal, trauma and social injustice out loud. That the ‘meltdowns’ comes so often might be a reflection of the world we live in.

Secondly, Coyne’s tweets resembled much of the moral preening he chastises. Amiel’s column wasn’t up long before people started tweeting – tweets to which Coyne wasted no time in criticising. In a response to one detractor Coyne asked, ‘who cares about your rage?’

He seems to be forgetting that, online at least, everyone and no one care. No one really needs to know about most details of an acquaintance’s daily life. We don’t care, but we don’t un-follow or we follow regardless.

Both Brown and Orenstein understood this fact years ago. The latter, with her emphasis on our commitment to performance: ‘If all the world was once a stage, it has now become a reality TV show: we mere players are not just aware of the camera; we mug for it.’ And Brown, with his appreciation for the Right Now-ness of tweeting: ‘Eating a sandwich becomes interesting, even important, if that action only has to occupy a moment in time.’

It’s during a crisis, then, that Twitter proves its worth as a social network and it’s no doubt why news organisations and their employees have taken to it (Coyne has amassed thousands of followers and tweets frequently). Social networks, Margaret Atwood discovered, ‘do not merely reflect the news: they also create it.’

If it’s okay to instantly communicate joy, humour, confusion, knowledge or sadness, why is rage so unacceptable? People tend to view anger as weak or dangerous, but rage in itself is not embarrassing. Put into context, however, and it can be. This is why the online community loves to expose tweets of privilege, ignorance or outright hatred. Tweeting an all-caps complaint that the barista made the wrong drink might be embarrassing. Calling the anger over blatant misogyny in the case of a teenager’s rape, or the rush to racism following the Boston bombings a ‘tantrum’ is dismissive.

When being polite fails, rage gets things done. History has demonstrated this over and over again. If we can’t rage collectively about sexism, what’s appropriate? Homophobia? Corruption? Racism? Apparently not, since Coyne tweeted another round of admonishments over the reaction to Brad Paisley’s ‘Accidental Racist’ just a few weeks later.

Professional journalists, unlike most people on Twitter, have a platform to organise their thoughts and carefully craft a reaction to world events. Twitter provides an out for historically marginalised groups, which has never existed before. Of course, this has the adverse effect of providing a soapbox for bigots, but this is no different from real life. Free speech is extended to all people and sometimes we don’t like what they have to say. When a public figure screws up, everyone gets a chance to respond. This is why so much activism has moved online.

In his response to the Brad Paisley controversy (which, weeks later, has begun to slip away into the pop culture archives for future reference) Coyne lamented the tendency of Twitter to limit critical thought and debate.

‘You shout out some simplistic slogan and get 400 other jackasses to agree with you.’

This isn’t entirely true. There are intelligent people online, which means that by tweeting you run the risk of 400 jackasses disagreeing with you, as well. There are probably many more intellects than there seems, though tweets won’t necessarily reflect that. Twitter encourages, first and foremost, arbitrary thought not analytic, long-winded expression. That’s what blogs and (if you’re lucky) regular columns in national newspapers are for. Nothing Andrew Coyne, Margaret Atwood or bell hooks has ever tweeted compares to what they’ve published in the traditional sense.

Is it fair, then, to judge a stranger’s capacity for thought by their online presence?

Critics of social media seem to forget that amid the over-shares and toxic provocation, worthwhile communication can be found. Not every controversy requires anything more than a few sentences of rebuttal, especially not when hundreds of people decide to throw in their two cents at the same time.

But when the issue is important enough, there is potential for real change – even if it’s just 140 characters at a time.