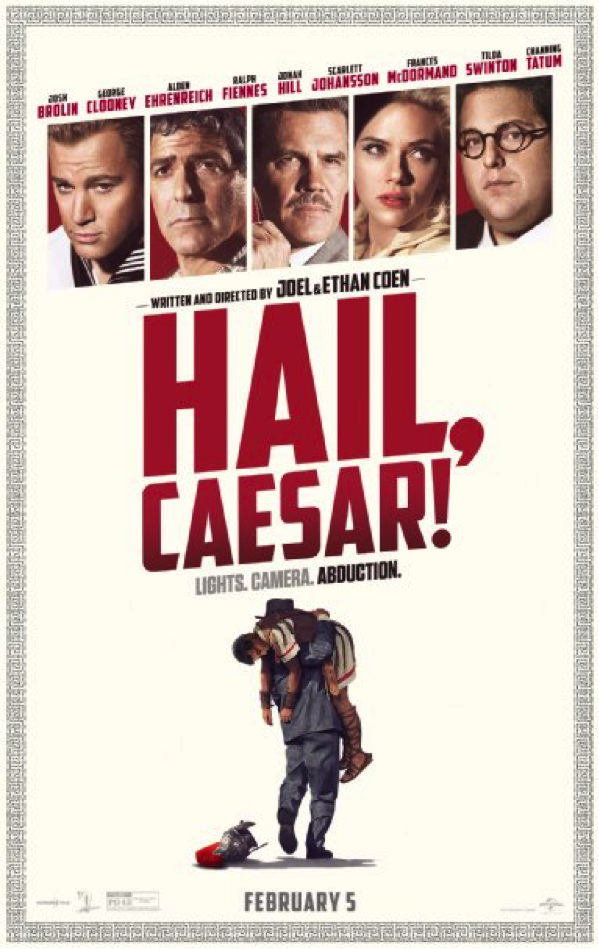

film review: hail, caesar!

Hail, Caesar! is about a day in the life of Eddie Mannix (Josh Brolin), a devout Catholic who works as a “fixer” for the fictional Capitol Studios in early 1950s Hollywood. Essentially, his role is to keep the image of the studio from deviating from the norms of the time, that of white Christian wholesomeness. The main source of conflict in the film comes when Baird Whitlock (George Clooney), the star of the film-within-a-film “Hail, Caesar!”, is captured by communist group, “The Future”. While on the surface, Hail, Caesar! is a light-hearted comedy, with ridiculous dance scenes and unbelievable stunts, its commentary on the political and cultural climate of the Hollywood’s “golden age” is an undercurrent that runs through even the silliest moments.

The Future is the main source of antagonism in the film, although as far as enemies go, they aren’t very threatening. Whitlock spends most of his time in captivity eating finger sandwiches and engaging in friendly Marxist discussions with his kidnappers, most of whom are film writers subtly pushing communist themes into their work. The whole storyline is a throwback to the McCarthyism of the early-to-mid 1950s, when the fear of communist infiltration in Hollywood was widely inflated, often unfairly targeting those who were Jewish or suspected to be homosexual. The name of The Future is wholly ironic, considering what is now known about the nature of McCarthyism. The threat of a communist future was never realised in the US because it was never really the threat it was made out to be. Communism and The Future, much like everything else in Hail, Caesar!, is a fantasy of the 1950s.

Christian morality also has a huge influence in Hail, Caesar! Baird Whitlock plays Antoninus, a Roman who becomes a follower of Jesus. Most likely, the character is a reference to Antoninus Pius, a Caesar who, while offering some protection to what we would now call “Christians”, was certainly never a convert. Nor was he even born until years after Jesus’ supposed death, and thus could not have proclaimed his conversion at the sight of the freshly-crucified corpse of Jesus, as “Hail, Caesar!” suggests. The film is a Christian propaganda epic in the same vein as Ben Hur, and while Mannix brings in representatives of Judeo-Christian faith to make sure that Jesus is not portrayed in an offensive manner (he is only briefly shot from behind), there is no call for historical accuracy—you never see Jesus’ face, but you do see his flowing blonde hair. Though Hail, Caesar! mocks the Christian propaganda films of the 1950s, the whitewashing of biblical films is still a relevant commentary for today, with fairly recent films like Noah and Exodus: Gods and Kings or even the currently-showing Gods of Egypt, being dominated by a white leading cast, despite the fact they are set in the MENA region.

Mannix, too, is an example of the strangeness of 1950s American-Christian morality. He is borderline scrupulous, obsessed with sin and compelled to confess with unnecessary frequency, yet it’s his job to cover up Hollywood scandals that deviate outside of moral norms, whether it be trying to work a way around actress DeeAnna Moran’s (Scarlett Johansson) pregnancy out of wedlock, or protecting Whitlock’s disturbing antics from being exposed in the media. He is the quintessential image of the American businessman of the 50s, who literally never sleeps and whose go-to method of problem-solving is slapping people into submission, but every action he makes is a Band-Aid for a bullet wound that will undoubtedly weep again. The image of propriety is only barely maintained at a time when America and its film industry teeter on the edge of massive cultural shifts.

In an article for Vulture, David Edelstein criticised Hail, Caesar! for being ‘overdeliberate’ and ‘movie fodder’, and it’s hard to disagree with his assertion that the film is an overly-saturated with tropes of American cinema’s golden age. But this doesn’t make the film any less enjoyable. There are plenty of easy laughs and bumbling characters, but that’s only the surface of a film which is complex in its commentary on 1950s American culture. There is still enough media out there that tends to romanticise the 50s as a simpler, more honest time, so we still need something every once in a while to remind us that the picture we have in our heads is merely a veneer that is very easy to shatter.