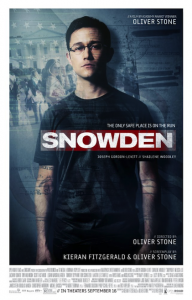

film review: snowden

The lone, brilliant man is the archetype in film I find the most groan-inducing. Spanning all genres, the lone, brilliant man can be the action hero who saves the world before time runs out, the only genius in the world who can crack the case, or the innovative creator of a technological advancement that changes the world. And although films that the lone, brilliant man inhabits can have a social justice angle, it is a thin veil for the vainglorious individual. These films celebrate one powerful force — usually white, straight, and wealthy — dominating. In political settings, this dominance is often over a general public they believe cannot think or act for themselves. They are tyrants in heroes’ clothing.

Almost immediately, Edward Snowden’s (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) lone brilliance is foreshadowed in this film when a CIA interviewer quotes one of Snowden’s favourite novels, Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged: ‘one man can stop the motor of the world’. It’s at this point that the viewer loses any hope of an objective critique of Snowden and his actions. Instead, it seems that we have a hero narrative.

This poses a problem for director, Oliver Stone. Edward Snowden is someone who a lot of people would feel uncomfortable calling an outright hero. His actions are still somewhat fresh in the minds of those who sit on all ends of the privacy-security spectrum. In identifying Snowden as a lone, brilliant man, he becomes exceptional, which runs a huge risk of appearing too arrogant or self-serving to an ambivalent audience. While the hero narrative serves the die-hard Snowden fans well, Stone also needs to create a character that the more wary can relate to on a base, universal level. He needs both a hero and an everyman — the exceptional and the unexceptional concurrently. It’s a very tenuous position to maintain.

Enter Lindsay Mills (Shailene Woodley), Snowden’s long-term girlfriend. The interactions between Snowden and Mills are often grounding moments in the film. On one hand, Snowden is at the top of his class in CIA school, the brightest of the brilliant, yet on the other, he is experiencing common relationship issues, such as differences in politics, lifestyle choices, and fears about infidelity. In their interactions, Snowden can come off poorly, underestimating her abilities, accusing her of having a poor work ethic, and with fluctuating and unfounded suspicions that she is cheating on him. While his depiction in these scenes is somewhat unflattering, the human insecurity within is relatable.

The introduction of Lindsay Mills into film is well done. Woodley’s attractiveness is not over-glossed in the traditional Hollywood style as a means to create a spark between the characters. Instead, Mills’ magnetism lies in her intelligence and willingness to speak her mind. Her healthy mistrust of government obviously influenced Snowden, who on their first meeting displayed blind faith to his government’s policies. Documentary director Laura Poitras (Melissa Leo), too, is set up as an influence to Snowden. She is the only person Snowden fully trusts with his information, and she is able to draw out the more personal elements of his moral struggle. Snowden becomes, then, a rare male character in film, in that he can admire and be influenced by women. And as a lone, brilliant man, it’s strange that he is influenced by anyone, that he hasn’t entered the film with a “perfect”, unwavering sense of morality to guide him.

By the end of Snowden, the traditional lone, brilliant man archetype has become muddled. We’re still supposed to see Snowden as the only person who had the intelligence and moral fortitude to do what he did, but it’s clear that without support from journalists, lawyers, people within the NSA, and even strangers, he would have failed unquestionably. It wasn’t one man who changed the motor of the world, but one who presented the opportunity. There are glimpses of Stone attempting to appreciate these people for risking their employment, reputation, and personal safety for the cause, but for the most part, the characters are mirrors — two-dimensional, and there to reflect Snowden’s glory upon himself.

And the film maintains some of the worst tropes that go along with the lone, brilliant man hero narrative. Yes, there is a scene at a strip club, where men talk strategy at a bar while women operate as background decoration. And in moments the language is hyperbolic, gravitas for the sake of gravitas. These were the most cringe-worthy aspects of the film—they were just too blatantly pedestrian to be taken seriously, which is not ideal for a film with such serious subject matter.

The release of Snowden will, for a least a little while, bring certain questions into the forefront. Were Snowden’s actions justified? Would he get a fair trial in the US? Does Joseph Gordon-Levitt pull off the Snowden voice? I cannot answer any of these questions for you, except to say that I have my own personal beliefs, and that you just kind of get used to JGL’s accent. The film itself is essentially Snowden propaganda, so whether or not you enjoy it will probably be largely based on what you already believe. But the film does succeed in showing its audience that behind this major political debate is a human being, and that the decisions he made were personal, as well as political. While it may not succeed in turning many people over to the Snowden side, it at least does a fine job at turning a public figure into a tangible person.