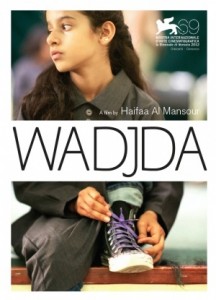

film review: wadjda

Saudi Arabia has long been veiled in mystery. The cultural gulf between the Islamic Kingdom and the West has fuelled speculation and criticism; Australians are at ends to understand a monarchical nation which limits citizens’ equality and individual rights. Saudi Arabia’s unequal treatment of women has become a focus of this criticism; Saudi women are not permitted to drive cars, to travel without a male guardian, and gender segregation is enforced in places of work, education and recreation. Saudi women are often perceived by the West as sites of oppression and ultimately, victims.

From a western perspective, herein lies the significance of Wadjda, an art-house film by Haifaa Al-Mansour which gives insight into the gendered cultural practices of Saudi Arabia and unites its international audience by conveying the universal value of freedom.

Ten-year-old school girl, Wadjda (Waad Mohammed) longs to buy a bike to race her best friend, an unheard of activity in Saudi Arabia. Her resilient spirit battles a disapproving headmistress, parents and society to raise the money by competing in a Koran recitation competition.

The hope and determination of the child protagonist in this film cuts through perceived gender differences such that audiences may understand the universal importance of freedom to personal happiness; Wadjda is greatly invested in her dream to ride a bike and is hurt by the attempts to thwart her in comments like ‘girls don’t ride bikes’ and the assertion by her friend that she’s physically unable.

Yet it is not the film’s aim to demand the viewer adopt any one belief. In an interview with The Guardian, al-Mansour noted:

‘I tried to be respectful of the culture. I tried to tell a story and retain my voice as an empowered woman, but I tell it softly… Change is a process and people need to take time to change at their own pace… You get your work done by engaging people and creating a space so that they will question.’

The resulting subtlety of Wadjda is powerful as it asks viewers to question their beliefs and come to answers in their own time. From the minimal use of background music, to the muted colour scheme and nuanced characterisation, the viewer bears witness to Wadjda’s story and has space to consider its implications.

Importantly for western audiences, the result may well be a deeper understanding of the historical and religious traditions and beliefs of a proud culture, and the complex task of achieving women’s rights within it. The well-developed, fallible characters deny popular stereotypes depicting Islamic men as barbarians and women as silent victims. Wadjda’s father (Sultan Al Assaf) is portrayed as loving both his wife and daughter, but as simultaneously willing to marry a second wife. Meanwhile, Wadjda’s mother (Reem Abdullah) is resentful and angry towards her husband, yet longs for his affection and approval. Wadjda herself is refreshingly impolite and non-compliant.

Too, the film reveals the lived effects of institutional discrimination; no matter her protests or attempts to fire him, Wadjda’s mother is forced to endure her aggressive driver for the three hour commute to work.

For Saudi Arabia, the significance of this film is threefold. Al-Mansour is Saudi Arabia’s first female director, and her film is the first to be shot entirely within the Kingdom’s borders. These feats proved difficult to achieve as Mansour struggled to find funding, received death threats and at times had to direct using a walkie talkie from inside a van as her working with men may have endangered the cast.

In these accomplishments, Wadjda marks a time of reform within Saudi Arabia. The King, Abdullah bin Abdulaziz Al Saud has implemented changes to government process and women’s rights. Liberalisation of foreign trade has encouraged its participation in international conversation and exposure to foreign cultures. And responding to mounting public demand, women have been granted the right to vote for representatives on the King’s advisory council (a right which will be enacted at the next election in 2015) and 20 percent of seats on this council are reserved for women.

Al-Mansour’s film will doubtless contribute to this change as it gives Saudi women a voice and subtly challenges tradition. If not for this, then the film is important as it has enabled young actress, Waad Mohammed to travel overseas for the first time and ‘shine’. Her parents will ban her from acting when she turns 16.

Wadjda is remarkable both for its scripted story, and for the story of its creation. These traits make it a landmark film in Saudi Arabian history, and offer international audiences a window to an otherwise foreign land and otherwise unheard voices.

It will be released in Australian cinemas on the 20th of March, 2014.