seeing scientology clearly: on alex gibney’s new documentary

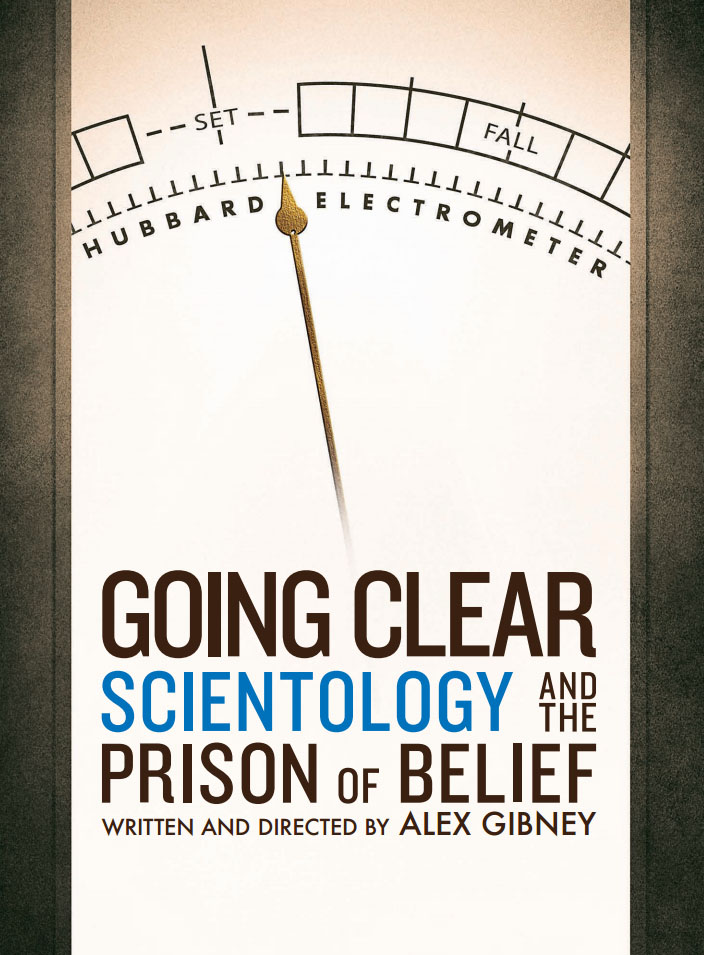

For most of us, the closest we’ve been to Scientology is watching this video of Tom Cruise. If Cruise’s flaring nostrils and hysteric laugh didn’t have you going cross eyed at the new age “religion,” Alex Gibney’s new documentary will. Going Clear: Scientology and the Prison of Belief draws back the curtain that has hung over the history and practices of Scientology since its inception, and shines a spotlight on its abuse and exploitation. In doing so, it illuminates more than a cult-like mega-church: it speaks on a human psychology more vulnerable than we’d like to admit.

Going Clear posits that Scientology is indistinguishable from the mind of its disturbed founder, L. Ron Hubbard. In 1952, Hubbard launched a step-by-step system for individuals to progress towards a state of enlightenment, free from negative thoughts and emotions. Beyond individual emancipation, Scientology would bring about ‘a civilisation without insanity, without criminals and without war.’ This system was built on Hubbard’s elaborate theories, and drawn in part from his early science fiction novels. They culminate in a creation narrative that involves aliens being frozen, dropped into earth’s volcanoes, and rising as spirits that inhabit our bodies. Gibney discredits Scientology from the get-go on this basis, following it up with a barrage of evidence revealing abuses committed by the church against its followers, from financial exploitation to physical and mental control.

Among the most damning abuses are instances of physical beatings and imprisonments, particularly under the current leadership of David Miscavige. One ex-Scientologist describes being separated from her new born child, only to later find the baby neglected, ill and with fruit flies crawling over her skin. Another remembers church members who were made to lick the bathroom floors as punishment for supposed wrongdoings. Beyond this, the church requires that members pay extortionate costs to progress through each level of enlightenment, pressures them for large donations and evades paying taxes. With Scientology accruing billions of dollars and establishing churches worldwide, Gibney’s exposé is rightly described as ‘chilling’.

Going Clear exposes more than abuses within the church. In tones that could almost be described as gloating, reviewers have flocked to poke fun at or trivialise Scientology as ‘creepy’ and a ‘racket’. But in self-lauding for our non-involvement, we’re missing an important point made by Gibney: under certain conditions, we are more pliable than we imagine. Scientology (like many radical ideologies) capitalises and depends upon this universally vulnerable human psychology.

The ex-Scientologists featured in Going Clear are intelligent and capable. They are ‘embarrassed’ and ‘ashamed’ of their past, and speak of feeling as though they were ‘brainwashed.’ Persuasion, coercion and control is shown to have influenced their ongoing commitment. In one instance, an ex-member describes being forced to endure a form of pseudo-therapy called ‘auditing’ that confused and depressed her. Conditioned to this environment, she rationalised her mistreatment. Another remarks that we are all vulnerable to committing to beliefs that make life ‘easier’. Perhaps the most confronting suggestion made by Going Clear is that this vulnerability is latent within us all.

Though interesting, the film’s content ultimately becomes repetitious and exhausting. Loosely chronological, the documentary slowly wanders through the history of Hubbard, the church’s establishment and into its current state. Gibney also delves into the church’s varied current practices. Half an hour is spent on its indoctrination of celebrities; then another on its abuse of other members. The use of visual motifs is inadequate to coherently bridge these diverse ideas, and in clambering to include everything, the film laboriously stretches into two hours. Viewers may well need an intermission, and the film overall needs a clearer and more concise structure.

Beyond these structural issues, Going Clear clearly has an argument to push. In neglecting alternate perspectives, it may be accused of committing the same bias and manipulation it deplores. The Church itself has refuted the film’s claims as ‘entirely false’, and accusations about prominent Scientologists John Travolta and Tom Cruise have been denied. Yet as The Independent’s Geoffrey MacNab argues, ‘the tone of Going Clear is inquisitive, not sensationalist’ and its arguments are well researched. Though objective criticism is difficult, the film marks a credible starting point for public scepticism and further investigation into the Church.

With a standing ovation from reviewers and a television premiere that broke records, it is easy to see why Scientology’s leaders are starting to sweat under the spotlight of Going Clear. Gibney has constructed a convincing exposé that reveals the workings of an otherwise secretive organisation. While we may feel baffled by and laugh at the mania of Tom Cruise, it seems there is reason for deeper concern.