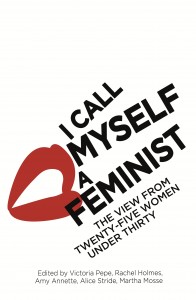

lip lit: i call myself a feminist

I called myself a feminist out loud for the first time only last year. Mostly I felt proud, but lurking underneath this pride was an undeniable layer of guilt. I Call Myself a Feminist—an anthology compiled by Victoria Pepe, Rachel Holmes, Amy Annette, Alice Stride and Martha Mosse—helped me answer two questions at the heart of this guilt: Firstly, why is ‘feminist’ still a dirty word? And secondly, why do I not feel worthy of the title?

I Call Myself a Feminist consists of 26 personal essays written by women under age 25; they range in focus from the subtlety of sexist language to the legacy of the suffragettes. Considered individually, they provide sophisticated and passionate insights into how some of the world’s most vibrant young feminists view their ideology. But when printed together, they project something that for some reason many of us seem to forget—that beyond a belief in gender equality, feminism is different for everyone.

Many of the essayists discuss intersectionality, the notion that different institutional oppressions such as religious discrimination, racism, and sexism cannot be examined as mutually exclusive. In considering feminism, for instance, it is important to remember that a woman’s experience of racism impacts her experience of misogyny, as do her religious views. Thus, no-one can really approach feminism in the same way.

This helps to explain both why feminism is the home of such incredible diversity, and why it is so important that this be universally acknowledged. As Jinan Younis states in her essay, ‘Manifesto for feminist intersectionality’: ‘Intersectional feminism is a lens though which we can define and critique our current struggles, and it is only through intersectionality that feminism can become more inclusive.’

These essays are not how-to guides for feminists; beyond the whole women-are-equal-to-men business, they do not come with a list of what to believe and how to feel. In fact, they completely deconstruct the possibility of any such list. And that is why they are important.

Many of the essayists marvel at why ‘feminism’ is such a stigmatised word, especially when phrases such as ‘good for a girl’ are still flung into conversation without half the uproar. Why is ‘good for a girl’ a more welcome, somehow less controversial description than ‘feminist’? We ingest media and culture without even realising that the ideals they shape in people are the basis of grander-scale sexism. Has our logic grown tired of us?

Bertie Brandes expresses this frustration perfectly in her essay ‘Stripper or Shaver?’, where she asks: ‘For how long will we blindly swallow a toxic culture and then reel in shock at the reality of sexism manifest in the day-to-day?’

For someone like me, who worries constantly about the subtle sexism within language (and how difficult it is to stop using), these essays provided relief. Even the most inspirational feminists struggle to shake off how they have been conditioned to speak and act. Louise O’Neill hits the nail on the head in her essay ‘My Journey to Feminism’, in which she describes her rocky road to labelling herself a feminist. In it, she confesses: ‘The manacles of a lifetime of cultural conditioning that has tried to convince me that gender is a biological fact rather than a social construct are more difficult to shake off than I would like.’

Similar to the message delivered by Roxane Gay’s Bad Feminist, these essays unite to reassure the reader that feminists are nowhere near perfect. They aren’t born perfect gender equality activists, nor do they always perform faultlessly under the feminist label. Because they are regular people, and regular people make mistakes. In ‘Women should get to be rubbish too’, Isabel Adomakoh Young says: ‘If you attribute perfection to women you pre-condemn them for failing to live up to it.’

Building the image of an ‘ideal’ feminist therefore creates the same problems regarding objectification and impossible standards involved with idealising women in general. What I adored most about I Call Myself a Feminist is its reassuring message: for as long as feminists are also people, the perfect feminist will never exist.

My response to this book will, of course, differ from another’s; this is evidently true of all books, but perhaps means more here. Different essays resonate with me, a white, non-religious Australian, than they might with someone religious or of a different cultural background. On the other hand, as someone under 25, these essays hit home in a very special way for their youthful perspectives, vigour and the general sense of finding one’s feet in ideology.

It’s easy for me to feel lost in feminist theory, and unsure of my own personal brand of feminism. I Call Myself a Feminist has taught me that it’s okay to be unsure. To disagree with, or to find faults in, any of the essays is thus only to acknowledge that the writer has walked a different path to feminism, and that different thorns have stuck to her feet along the way.

As Kathleen Hanna once said: ‘There’s just as many different kinds of feminism as there are women in the world.’ They are all inspirational, and they are all worthy.

*

I Call Myself a Feminist, edited by Victoria Pepe

Hachette, 2015

PB 336pp

RRP $32.99

Pingback: Review: I Call Myself a Feminist by Victoria Pepe (ed.) – J. M. Miller