lip lit: lemons in the chicken wire

Alison Whittaker’s debut collection, Lemons in the Chicken Wire, is a refreshingly authentic and accessible new addition to the Australian poetry landscape. The collection is grounded in simplicity yet explores complex issues such as sexuality, racism and family negligence. Whittaker, who received the State Library of Queensland’s black&write! Indigenous Writing Fellowship, also explores the history of Australia, particularly those of Indigenous Australians, and connection with the land. The collection took four years to write, and each poem, individual line and word have clearly all received much careful attention.

From the opening stanza in the very first poem, ‘Land-ed’, the reader is captivated by Whittaker’s imagery: ‘land/ takes dead skin from my feet’. We are also introduced to the recurring theme of simultaneous displacement and intertwinement of the city and the land: ‘while the city/ puts dead shoes on my feet’. The second poem, ‘Bangers//Mash’, contains the first of many instances of Indigenous slang: ‘mob eat the skin’. Whittaker’s poetry constantly pushes the reader to think about objects and language in new ways, for example, the ‘op shop sweater’ that ‘wore flat, and with fat, thin’. This is also achieved through the use of poetic devices. Alliteration (such as ‘I was born in the boiler pot/ where sausages lift their skins’) and repetition give the poetry a grounded quality and an easy accessibility. Earthy imagery is also repeated throughout the collection, such as ‘the grout sands her fingernails’ in the poem ‘Re –; In – ’, recalling the narrator’s fascination with the land. The poetic devices enhance the literary merit of the work without overwhelming the reader; instead, they give a beauty to the narrator’s exploration of complex topics.

Homosexuality is touched upon in ‘Insider Knowledge’, which details how the narrator’s family has treated her due to her sexuality. The family’s reactions reflect those in real-life coming-out stories, which adds to the collection’s easy accessibility. The narrator’s refusal to sentimentalise her family becomes even more evident in ‘Preface: Another Funeral’. There is a verisimilitude to her family dynamics, one that informs her portrayal of her troubled relationship with her parents. Their flaws, and hers, are on full display, evoking sympathy for the narrator.

As aforementioned, connection to the land is also a recurring theme in Whittaker’s poetry. ‘Carry the One’ introduces the idea that the history of this land is her history as well; the land’s process of growing up is her growing up. In ‘Jim’s Carpet Cleaning’, the land is treated with reverence. The entire poem consists of only three lines, yet is one of the most striking of the collection. The narrator’s culture sees dirt on the floor as a source of pride, physical proof of their connection to the land, yet the title is the name of a cleaning business, a reminder that other people view dirt as something to be rid of.

Whittaker is also unafraid to explore race relations. In ‘Carry the One’, the narrator ridicules the commemoration of the First Fleet’s arrival, of ‘learning about Cook/ but not Pemulwuy’, as referred to in later poem, ‘The Tender Sheds’. This is explored further in ‘O’ Eureka!’, a poem that depicts the changing relationship between the narrator and her Nan now that she is at university. Nan sees her granddaughter as ‘turning white’, believing that she is somehow lesser than her granddaughter as she doesn’t use ‘white theory word[s]’. Race, particularly the uncertainty surrounding it, is once again the central focus of ‘Come Back Black’. The poem contains an almost melodic, chant-like last stanza that explores the blurred distinction between black and white cultures.

One of the final poems, ‘Countrylink X-Plorer: A High School Essay’, details the narrator’s gradual acceptance of herself. The train journey reflects the journey the narrator has taken the reader on throughout the collection; we have watched as ‘The train [which once] shift[ed] between two places and two selves’ now ‘merged two tired selves/ ‘til each fed the other’. There is no longer a dichotomy between her selves, evoking a sense of hope in the reader that there may be a way for the cultures in Australia to peacefully live alongside, or even coalesce with, each other.

*

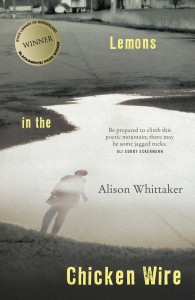

Lemons in the Chicken Wire by Alison Whittaker

Magabala Books, 2016

PB 64pp, RRP $22.95