lip lit: on immunity

The vaccination debate heated up again recently when in March four-week old Riley Hughes died from whooping cough in Perth. Riley was too young to have had the whooping cough vaccine and therefore relied on the immunity of those around him to protect him from the disease. With a growing number of parents choosing not to vaccinate their children, diseases which were eradicated are returning.

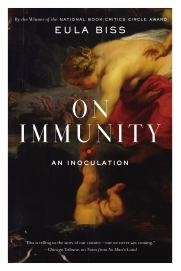

The vaccination debate is a passionate one. Choosing to vaccinate or choosing not to vaccinate are both decisions made out of love, and therefore the debate is one driven by a high-level of emotion. Given the subject matter, I expected Eula Bliss’ book On Immunity: An Inoculation to be full of passion, emotion and self-righteous debate. Yet Bliss strips the emotion from the subject, paring it back to the facts and her personal experiences as she investigates the history of immunisation and examines the arguments surrounding vaccines.

At first, the lack of emotion in the writing feels wrong. Vaccination is a matter of life and death and such a methodical examination doesn’t feel right. But it soon becomes apparent that examining the topic beyond emotion is exactly what needs to be done. Emotion can cloud judgement and distort the facts, while fuelling a heated debate.

Bliss traces the history of immunisation back to milkmaids in eighteenth-century England. At that time, nearly everyone in England had contracted smallpox, and the scars left behind a tell-tale sign of the disease. It was discovered that milkmaids who developed blisters after milking a cow blistered with cowpox did not contract smallpox. Human experiments followed this discovery: a farmer drove pus from a cowpox-infected cow beneath the skin of his wife and two sons. His wife became ill before recovering, while his sons only had mild reactions and subsequently never contracted smallpox in their lives. Bliss includes this history in order to provide context and so the reader understands the origins of the practice as it exists today. Vaccination began with a farmer’s act of love, as he wished to save his family from a horrible disease.

Woven into the history and science of vaccines, Bliss shares some of her own anecdotal experience concerning her son. Before vaccinating her son, she researched the concept thoroughly, and continued to question every consequent vaccine. For example, the doctor plans on giving her son a chicken pox immunisation along with other scheduled vaccines and Bliss asks ‘… could we limit my son’s vaccines to those that protect against diseases that could kill him?’ The doctor then explains why the chicken pox vaccine is a good idea and Bliss relents.

While Bliss does vaccinate her child, she does not chastise those who choose not to, especially given there have been instances where vaccines have been used as a weapon. For example, Eula writes that the CIA administered a fake vaccination campaign in Pakistan when they were in pursuit of Osama Bin Laden, administering the real hep B vaccination but not the three shots required for immunity. This deception cost lives, and lead to vaccination campaigns against diseases such as polio being suspended. Bliss also writes about a friend of hers who was born during the Vietnam war and exposed to Agent Orange in the womb:

After coming to this country, she did not vaccinate her children as infants, for a number of reasons, including her sense that it was not safe. I disagreed with her uneasily, knowing that my understanding of safety had been forged in a life more protected than hers. I could not ask her to risk her children for the benefit of the citizens of the country that had put her in danger. The best I could do, I determined, was hope that my own child’s body might help shield them from disease. If vaccination can be conscripted into acts of war, it can still be instrumental in acts of love.

It is sentiments like these, woven throughout the book in tiny snippets, which really drive the discussion and make the reader pause for a moment to think. Bliss comments, ‘I suspect that Coca-Cola, unpoisoned, is more harmful to our children than vaccination’, and ‘we seem to believe, against all evidence, that nature is entirely benevolent.’

These snippets beautifully capture the point, without forcing it down the reader’s throat: the evidence tells us to vaccinate. Due to the neutral, unemotional tone of the book, there is little on the page to enrage those who choose not to vaccinate their children, apart from the fact that Bliss chooses to vaccinate.

There is so much written on the topic of vaccination that to weed through all the research and determine what is relevant and what is not is a daunting proposition. Eula Bliss’ On Immunity: An Inoculation is an excellent place to start for anyone who wants to do some research of their own.