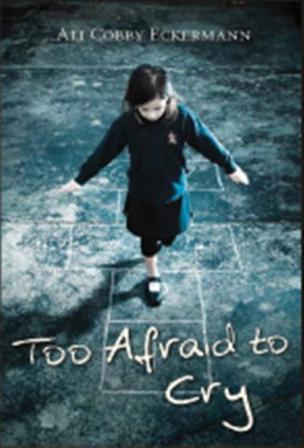

lip verse: too afraid to cry

Ali Cobby Eckermann was too afraid to cry, and I was too afraid to put down her memoir till I had come to the end and knew that she was going to be okay. This is the extraordinary true story of Eckermann’s upbringing as a child of the stolen generation—taken from her Indigenous family at birth and raised by a white family. Frightened and confused, she endures racism and sexual abuse at the hands of adults and other kids, growing silent and withdrawn.

Uncle started to kiss me. His chin was all scratchy from not shaving. It felt funny, and I felt like laughing. But when he pushed his tongue down into my throat I screamed. No noise could come out, and I couldn’t breathe. He had put his body on top of mine, and I couldn’t move.

* * *

My foster brother had a friend who sometimes stayed overnight on the farm. He was a prefect at our school. I don’t know why Mum let him stay because he didn’t play games with us. He was much older than me, and when Mum and Dad were busy working on the farm he did things to me he wasn’t supposed to do. I knew it was bad what he did to me.

* * *

He told me not to say anything. And I couldn’t tell Mum because I was scared she would yell at me and smack me. I though Mum and Dad would stop loving me if I told them.

* * *

Someone held me while other hands pulled my underpants down. There was a strange noise in my ears, like a faraway scream, but I could still hear the sounds of those doing the laughing and teasing. They said they wanted to know if I was the same as other girls.

* * *

Grandma always said that we must never talk about ‘down there’ in our underpants. So I said nothing…

One of the most interesting aspects of the book is the way that it alternates between prose and poetry. The chapters are short episodes told in a straightforward, unsentimental voice. There is a poem between most chapters, which opens up space for the reader to pause and contemplate wider themes and relate the narrator’s experiences to other Indigenous people’s across the country and the years. The poems are all in the present tense and have a quality of timelessness to them.

a lavender bush has died

in her eyes

the bitterness of lime

flavours her tears

It burns to blink

* * *

They used the ink from inside a felt marker pen to paint my face dark brown, and drew dark brown blotches on my light brown skin. I watched the clouds. I watched trust disappear.

* * *

My eyes lost some meaning that day. I hated living a life where so many people hurt me, and in that moment I began to hate them back.

As a young adult, Eckermann finds herself in a destructive spiral of alcohol and substance abuse, as well as a victim of domestic violence. She even contemplates suicide. Her story not only exposes Australia’s shocking history of cruelty and neglect towards its Indigenous people, but also depicts a patriarchal society that too often shames women and fails to support or protect them when they are most vulnerable.

That first time you stopped in the park

Sitting down talking to the mob

You thought you could handle the pace

Drinking goon and telling yarns

As the day turned to yellow

You passed out drunk on the grass

Pretending you were asleep when the fighting started

Pretending you didn’t notice his black hands on your tits

Pretending deadliness when he staggered away.

* * *

The sunrise illuminated the bruises on my face. Bones said he was really sorry, and that he really liked me, and that I better not leave him. He had punched me in the face when he was drinking. He punched me in the face every payday. I was getting used to it.

* * *

At eighteen I would be the first unmarried pregnancy in our small country town, and I knew Mum and Dad were ashamed of me. The younger siblings looked at me like I was the devil. I felt like I was carrying the devil inside me.

* * *

One night they told me they were working for the escort agency. They were prostitutes; their drug addiction had forced them. I pretended I didn’t care, but inside I was feeling shocked. Some of them had toddlers; I worried about the kids.

* * *

Hey lovey do you want to

get your rocks off?

* * *

One day she didn’t come to work. The boss’s wife told me Ida’s husband had beaten her up, and that she was being flown to hospital with the Royal Flying Doctor. We all heard the plane fly overhead.

* * *

While Dave was at work I would spend hours looking at the rafters of our shed house. Sometimes I would hold a length of rope on my lap.

* * *

I’ve choked on the curse

of man she said

it’s the redolence of bad

memory she said

it’s the funk of rape

enjoyment she said

it’s the pong of painful

marriage she said

While reading the book, I couldn’t imagine how this troubled soul could ever overcome her past hurts to become the esteemed writer I know to be Ali Cobby Eckermann (winner of this year’s NSW Premiers Poetry Prize and Book of the Year Award among many others). But through eventually reconnecting with her Aboriginal family and heritage, she is finally able to heal her fractured sense of self and begin writing and sharing her story.

They look into my face and into my eyes. They dance and sing around me. They welcome me back to my traditional country. They give me my skin name. They rub me with their healing powers and heal me using traditional medicine. They rub me again and remove the ice block from inside me. Then they heal the hole in my guts.

This book is both an easy read and a difficult one—that is, the writing is very accessible but the subject matter is confronting; so many of the experiences Eckermann has lived through and the things she has seen are sad and horrible. Nevertheless, there is a lot of hope in these pages, too, and the honesty with which she has told her story is testament to a brave spirit and strong voice that will no longer be silenced. The book itself is tremendously inspiring as a tribute to the astounding human capacity to rehabilitate, reinvent, reimagine and rediscover oneself, even in the face of unfathomable difficulties.

I have learnt many things from alcoholics and addicts more messed up than me. Sometimes it is amazing who you can learn from. Sometimes it is strange where you feel safe.

* * *

there is love in the wind by the singing rock

down the river by the ancient tree

* * *

you good now girl

go get the world

Too Afraid to Cry is published by Ilura Press.

Bronwyn Lovell is an emerging poet living in Melbourne. Her poetry has been published in Antipodes, Cordite Poetry Review and the Global Poetry Anthology. She was shortlisted for the 2011 Montreal International Poetry Prize. Look out for her work in Australian Love Poems 2013, coming soon to a bookstore near you, or see her perform live at the Bendigo Writers Festival in August.