sex education: it’s a feminist issue

Despite frequently being a compulsory part of modern-day educations, sex and relationship education, or SRE, is often brushed to one side in schools. In the UK, one in four pupils receives none at all, and many of those who do get it report it to be unsatisfactory or even factually incorrect. Many parents are unwilling to accept a more comprehensive and varied SRE program, fearing that educating kids about sex is tantamount to encouraging it. But with the vast majority of teenage pregnancies being classed as unplanned or unwanted and thousands of teens stuck in abusive relationships, the need to educate young people on the relationships they have isn’t just an issue for the parents and teachers of the world – it’s for feminists too.

Education about rape and consent, attitudes towards gender and sexuality, information about what constitutes as unhealthy relationships – all of these issues are both central parts of many feminist campaigns and the building blocks of SRE. While it might seem unpalatable to some parents that topics such as rape should be on the school syllabus, recent events such as the Maryville case, the Steubenville case and the Manchester sex attacks cannot be treated as anomalies. A study done by Jacqueline Goodchilds found that a disturbing number of high schools students – both male and female – could conceive of multiple situations in which it would be acceptable to force someone to have sex with you. While basic information on rape is supposedly given in schools (although the lackadaisical approach to regulating SRE means that this is not necessarily always the case), without a concentrated effort to tackle the complexity and ingrained nature of rape culture, we are failing to help our future generations build a better society than we have created for ourselves.

This education doesn’t have to start with sex. The first time a child starts attending full-time schooling is one of the first opportunities for them to start forming close relationships outside of their immediate families. In theory, helping children understand the appropriate way to carry out these relationships is part of the curriculum; in practice, it is not. Poor regulation and a lack of regard from the government means that little of what is supposed to be taught to primary school children reaches them, being passed over and considered unimportant or trivial. While SRE certainly shouldn’t take priority over other aspects of academia, giving young children a grasp on appropriate behaviour within relationships, such as teaching them that the wishes of others must be respected, has a trickle-down effect into later life.

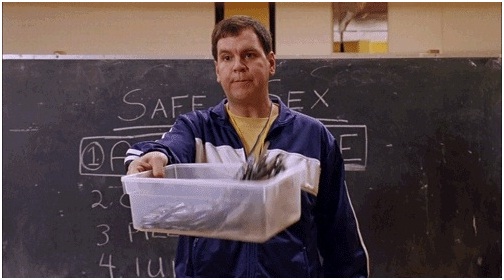

When the time does come to teach about sex, the current syllabus leaves much to be desired. As many schools teach only the bare bones of what qualifies as SRE – essentially the biology of reproductive sex – the opportunity to cultivate healthy attitudes towards sex and relationships is lost. Rather than give comprehensive education about sex, sexuality, gender and relationships, the combined force of unwilling schools, uncaring governments and overzealous parents are allowing children to leave school with nothing more than a cursory knowledge of sexual practice. Art may well reflect life, but it’s depressing to know that that infamous scene from Mean Girls is more or less the full extent of many institutions’ sex and relationship education.

Throughout their growth from children to adolescents to adults, today’s kids have more exposure to sexually explicit or inappropriate material than any other previous generation. The nature of an ever-expanding media means that even with the best efforts, there is simply no way to control the exposure to sex and the attitudes around it that a child receives. With one of the most popular songs around right now glorifying rape, some of the best-selling books romanticising abuse, and the pornographic material being accessed by teenagers gradually becoming more violent and explicit, we can’t pretend that it is the introduction of sex education that will lead kids to a life of debauchery. The reality is that with or without SRE, young people have plenty of access to information about sex. The point of SRE is to ensure that that information is correct. In the same way that IT lessons must develop as technology moves on and computer literacy becomes an increasingly important part of adult working life, SRE must adapt to the changing nature of sex and its place in society.

If those ideas about consent and respect in relationships are planted at a young age, then there will be fewer people walking around complicit in rape culture later on. If we inform and educate about gender and sexuality before the prejudiced that are prevalent within society have a chance to take effect, then we reduce the number of homophobes LGBTIQ people are forced to encounter in the future. Preventing young vulnerable minds from growing up thinking that porn actors should be the template for their own relationships is a step towards encouraging healthy couples over misguided attempts to replicate potentially damaging displays of power and submission. Feminism is about undoing centuries of inequality – if we can use sex and relationship education to help combat young people’s attitudes and ideas about sex that lead to bad adult relationships, we eradicate some of the problems feminism strives to solve before they even begin.