why we need feminist art criticism: a response to jonathan jones

I once had a lecturer who remembered attending a symposium on feminist art history in the 1980s, just after Griselda Pollock’s landmark text Vision and Difference: Feminism, Femininity and Histories of Art had been published. Pollock had attended this particular symposium, along with other prominent feminist art historians, artists and critics. Summing up his impressions of the debate, my lecturer told us, ‘well, all I can say is the sisterhood really got their claws out’.

Right. Allow me to infer that a group of academics and practitioners had a heated intellectual discussion, in which they presumably tabled various opinions on the issues common to them all. They had a debate. Not a pillow fight.

Difference of opinion in feminism isn’t a betrayal of ‘the sisterhood’. It is a part of the process of forming judgement, learning about the world, and acknowledging the necessity of difference itself. Difference serves knowledge.

My own approach to art history and criticism is to regard art by women as important, and deserving of attention in its own right. I think we need to use our resources not only to critique patriarchal biases and institutional prejudice, but also to take women seriously. It’s not only about rectifying history, but about actually changing it. Art historians like Susan Best and Catherine de Zegher also take this view, asking what art by women adds, rather than focusing on the ways it is constrained. This not only serves to elevate women’s art, but invigorates the entire field, making us question long-held assumptions and examine our own practices. I want to write about female artists, not as a kind of separate sideline to male art history (or, ‘everything else’), but because their work is rigorous, innovative and culturally enriching. And I shouldn’t have to limit its efficacy by only ‘defending’ it.

However, it seems I do have to defend it. One thing that has made it glaringly apparent the marginal role that women’s art still occupies are the recent articles by Jonathan Jones, a prominent art critic who writes for the British Guardian newspaper.

Jones typically ascribes to the ‘it’s good’ or ‘it’s shit’ school of art criticism, which is perhaps its laziest manifestation, the most meaningless and definitely the most boring. His pretensions are matched only by his near-complete embodiment of the kind of conservative, elitist and patronizing attitudes historically associated with the art establishment. You could run a minibus off the sense of self-satisfaction in which Jones is clearly indulging in his profile picture on the Guardian website. But what Jones has made me realize is just how desperately we need feminism in art criticism.

Last week, Jones enlightened us all to the fact that performance art is ‘silly’. Jones dismisses the entire genre on the basis of a work by the German artist Milo Moiré, whose videos have become sensations on YouTube. Titled ‘PlopEgg’ paintings, Moiré’s videos show the artist inserting an ink and paint-filled egg into her vaginal canal, and then allowing it to ‘plop’ onto the canvas. Like Millie Brown (an artist recently made famous by Lady Gaga, whose work involves her vomiting dyed milk onto canvas), Moiré uses her body to create a kind of expressionist painting. Jones went on to describe Moiré’s performance as ‘absurd, gratuitous, trite and desperate’, and to opine that the entire genre epitomises ‘cultural inanity’.

I’m not interested in defending the ‘greatness’ of the ‘PlopEgg’ paintings. For me, that’s not effective criticism, especially since there are so many better examples of performance art worthy of discussion. For what it’s worth, Moiré conflates artistic creation with female biological processes, suggesting a continuity between the creative act and the female body; I’m not sure whether Jones missed Moiré’s obvious allusion to Jackson Pollock’s drip paintings, with their own associations of male virility with creativity. Moiré pays homage to a previous generation of feminist performance art, particularly Carolee Schneeman’s key work ‘Interior Scroll’, as well as ‘Meat Joy’. In doing so, Moiré certainly re-treads territory already mined more astutely and movingly by Schneeman, and also the fluxus artist Shigeko Kubota, almost fifty years ago now. Jones would know all this if he bothered to do any research.

What I am interested in is not only Jones’ evident lack of knowledge of the genre of performance art, but his shaming, belittling and trivializing of women’s art practice.

The ephemeral nature of performance makes it tricky to place in history. But rather than giving any art historical context, Jones supports his argument against performance through its depiction in the film The Great Beauty, itself filled with ugly and caricaturish representations of women, among them a reference to Marina Abramovic, the most famous performance artist working today (and one of only two artists Jones lists as ‘exceptions’ to the rule that performance is crap- probably because he doesn’t actually know any others).

Performance has been ingrained in art practice for centuries, but it has often been relegated to the margins, forgotten, and passed over. While performance has always been an element of art practice, performance and body art emerged as a distinct genre in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Crucially, it was a genre embraced by women.

The reasons for the establishment of performance as an area of feminist practice were twofold. Firstly, because it was a field as yet un-dominated by men, women were able to explore its potential on their own terms. Secondly, performance crystallized around the body as the site of exploration. Works like Moiré’s and Brown’s relate to the history of depictions of the female body. The body, as Barbara Kruger succinctly put it, is ‘a battleground’. With the advent of performance, female bodies, which had been the subject of paintings, their nakedness seen only as nudity for the male gaze, began to explore the very line between object and subject that had rendered their presence in art largely mute. What happens when paintings begin to speak back, to claim some kind of agency, to threaten the status quo? In the recent works Jones ridicules, female artists vomit and excrete paint, both orifices women have historically been encouraged to keep closed. These are bodies as exploded paintings.

If feminist performance art often seeks to claim the body back from the hostile appropriation of the male gaze, it’s interesting that Jones ridicules and sexualizes Moiré’s body. He writes sarcastically, ‘the nudity, apparently, is artistically essential’, as though Moiré’s decision to present her body unclothed as an artist is somehow an affront, while if she were to give over her naked image as a painter’s model this would be fine. The title of his article which brands her ‘the artist who lays eggs with her vagina’ reduces the artist to a part of her anatomy, and functions, as several commenters mentioned, as crude ‘clickbait’. He turns her performance into a kind of sex show, one he is able to simultaneously ridicule and get off on.

Jones not only dismisses an area of practice to which women have made a significant contribution, his whole critical agenda serves to re-inscribe patriarchal paradigms. On his blog, he has been compiling daily ‘Top 10s’, churning out facile BuzzFeed-style lists ranking works according to various themes. Talk about cultural inanity.

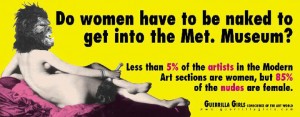

Where he includes some women artists, Jones completely misinterprets their work, drowning their voices in the well of a paternalist art history. His list of ‘Top 10 Female Nudes in Art’ demonstrates that he is at least aware of feminist art. Alongside Titian’s Venus of Urbino, Jones acknowledges works by Hannah Wilke and Guerilla Girls, which challenged the male gaze and the institutional biases of the museum. As the Guerilla Girls’ poster pointed out, 85% of the nudes depicted in the Metropolitan Museum were female, compared with only 5% of the artists. While it is encouraging that Jones is aware of some feminist art, I question whether this work is a ‘nude’ at all. Rather, it is a political poster commenting on the nude, a call to arms.

In ‘Top 10 Sexiest Works of Art’, Jones includes Tracey Emin’s video ‘Those Who Suffer Love’, demonstrating that even a feminist artwork dealing with isolation, love and intimacy can still be mined for male titillation. As he writes, the work ‘manages to be both poetic, as an image of loneliness, and exciting, as an image of pleasure’. Jones neglects to include works by women which might legitimately be called ‘sexy’, in that they explore erotic experience. Schneeman’s video Fuses, for example, is a sensitive, fleshy exploration of real sex, intimately hand-coloured and scratched, presenting sex from a female perspective, but this doesn’t make it into the ‘Top 10’.

Jones really hits his sexist stride in his ‘Top 10 Greatest Artworks Ever’, including not one work by a woman. This may be because women artists are given a whole list to themselves: ‘Top 10 Most Subversive Women Artists in History’. A whole separate category, as though art by women is only a kind of quirky sideline to the ‘great’ male works of history, ‘subverting’ the natural order by well, just being female. The only thing the artists have in common is that they, like Moiré, have vaginas. Jones ghettoizes significant artists like Eva Hesse, Louise Bourgeois and Claude Cahun, making some passing remarks about their commentaries on gender and sexuality. In his list of ‘greatest’ works, however, he waxes lyrical about the mysteries of humanity as revealed by Da Vinci and Pollock.

While Jones titles the list ‘the greatest’ artworks, the introduction does note that it’s merely a list of his ‘favourites’. Perhaps we should conclude that his favourites just happen to be exclusively white, male, Western and created prior to 1950. But for someone whose career is in shaping taste, frankly, that’s just not good enough. Jones’ inability to think critically about art is embarrassing, retrograde, and impedes meaningful judgement.

Criticism can be powerful. Often unattached to museums and galleries, critics are able to influence the reception of artists and their work, not only to proclaim what’s ‘good’ and what’s ‘bad’, but to really examine art and the way we respond to it. If we take art by women seriously, we’ll find that existing paradigms of judgment don’t match up to the challenges being made by artists. To continue to rank works according to patriarchal criteria is lazy, boring and has no place in the contemporary world.

Feminism isn’t only important in order to account for the work made by women, it’s important because it demands a better kind of a criticism. The process of feminist criticism might actually look something like that debate my lecturer talked about all those years ago: lively, intelligent, progressive and vital.

Pingback: Feminist News Round-up: 10.05.14 | lip magazine