books you should have read by now: fantomina

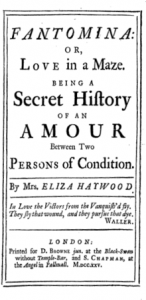

Fantomina: or, Love in a Maze was published in 1725. Its author, Eliza Haywood had an indisputably impressive writing career; she authored numerous works within a diverse range of genres. Although her writing was experimental in both form and content, she has, until recently, been curiously absent from the literary canon and is scarcely known beyond academic criticism and university reading lists. Some critics have also questioned the categorisation of Haywood’s works within contemporary feminist scholarship. While there are certainly aspects of the text that are open to interpretation, I believe that the strongly subversive nature of Fantomina conveys a clear feminist message.

Regrettably, there are few verifiable facts pertaining to Haywood’s biography, and consequently there may have been a number of factors catalysing her removal from canonical literature. In my own opinion, however, gender is a key feature in her decline.

Significant evidence of this can be located in the slander published by fellow writers of the era, particularly male writers. The most notable publication is British poet Alexander Pope’s The Dunciad (1728), whereby Pope sought to malign Haywood’s reputation by penning allusions to her alleged promiscuity and to her illegitimate children.

Conversely, there were critics who persisted in assessing Haywood’s works with reference to her male counterparts; and thus, as academic Dale Spender notes, Haywood often became known as the female equivalent to leading male writers, including Daniel Defoe. In both respects, Haywood’s merit, or purported lack thereof, remained firmly entrenched in her status as a woman.

The arguably sexist treatment of Haywood and her partial fade into literary obscurity should not constitute reasons to read Fantomina. The quality of Haywood’s writing speaks for itself: the novella is a remarkably fresh, mildly playful, and innovative reading of female seduction in the eighteenth-century. Haywood successfully subverts the gendered social binaries of the 1700s by writing a tale of female sexuality and intrigue from the perspective of an empowered, determined protagonist.

Fantomina follows the exploits of an unnamed Lady who becomes infatuated with a man, Beauplaisir. In an effort to retain his attention, she seduces him in a number of different guises: prostitute, country girl, grieving widow and Lady. Crucial to understanding this plot is Haywood’s assertion in Fantomina that women are usually faithful to their romantic partners, while men are traditionally unfaithful. Haywood, however, diverges from straightforward compliance with these gendered stereotypes in her novella.

In Fantomina, Haywood effectively subverts typical narrative conventions of the era by depicting a female character that does not react in the usual ‘feminine’ way to her lover’s unfaithfulness. In their introduction of Fantomina and Other Works, Alexander Pettit, Margaret Case Croskery and Anna C. Patchias observe that such subversion by Haywood exemplifies a deviation from what critic John J. Richetti calls the ‘persecuted maiden’ storyline.

Conventional eighteenth-century female protagonists within the so-called ‘persecuted maiden’ narrative would have been portrayed as victimised women who were heartbroken when betrayed by adulterous men. Haywood instead projects an image of an empowered and proactive woman who ultimately ‘did in every Thing as her Inclinations or Humours render’d most agreeable to her’.

Haywood’s protagonist is undoubtedly my favourite aspect of this novella. The heroine refuses to be predictably passive in Beauplaisir’s blatant unfaithfulness. Instead, she is intelligent, daring and bold in continuing her seduction and romantic pursuit of her lover. By the end of the novella, it appears as though Beauplaisir and Haywood’s unnamed protagonist have become rivals in outwitting each other: the former in attempting to obtain his lover’s identity and the latter in keeping that identity a secret. This match between man and woman is largely portrayed as equal, and the reader is encouraged to perceive the protagonist as wily and clever, always one step ahead in her game of seduction:

‘she could not forbear laughing heartily to think of the Tricks she had play’d him, and applauding her own Strength of Genius, and Force of Resolution, which by such unthought-of Ways could triumph over her Lover’s Inconstancy…’

And even following the most sombre, and dramatic moments of the text, such as when the heroine is raped, Haywood refuses to cast her as completely victimised or broken. Rather, the protagonist channels her unhappiness into her scheme to ensure that Beauplaisir remains ‘sincere and constant’ in his affections.

The fact that Haywood depicted a relatively empowered female character in Fantomina does not mean that she overlooked the social constraints existing at the time. The masquerade theme, and the accompanying secrecy, arguably represents society’s emphasis on repressing female sexuality. This is evidenced by the protagonist’s keen strategising to ensure that her identity is never revealed during her sexual exploits: ‘the Intreague being a Secret, my Disgrace will be so too’.

Despite conspicuous awareness of female ‘Reputation’ and ‘Virtue’, Haywood does not refrain from portraying her female main character as capable of passion. In her final ‘disguise’ particularly, the protagonist is open about her sexual desire, and does not present herself as modest or demure when revealing this desire to Beauplaisir. Thus, despite the social framework of idealised femininity, and albeit through layers of secrecy and masquerade, Haywood depicts an alternative representation of female sexuality to her readership.

Eliza Haywood’s literary talents are clearly evident in Fantomina, and although debate continues to somewhat shroud her place within feminist criticism, there remains significant evidence of a feminist message within the novella. Not least of all, this message appears in the subversion of conventional theme and storyline, and the prominence of a delightfully enterprising heroine, who is quite atypical of a time favouring female chastity, purity and the ‘persecuted maiden’.