Destiny Deacon

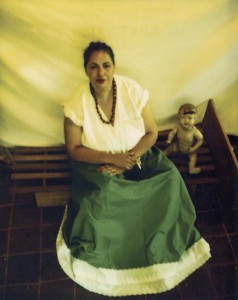

In the self-portrait currently hanging in Melbourne Uni’s Ian Potter Museum of Art, Destiny Deacon sits placidly with her hands folded on her lap, dressed in a flowing green skirt and folky jewellery, her hair pulled back in a neat bun. Beside her sits Carol, one of the many black baby dolls Destiny has ‘rescued’ and given new life in her art.

Destiny Deacon is one of the most interesting and controversial contemporary Aboriginal artists, creating haunting photographs that explore the layers of identity and the experience of the modern Aboriginal woman. While I’m probably not qualified to comment on the political implications of her work, nor the cultural significance to the indigenous communities, I see her photographs as harrowing portraits that express one of the most universal concerns of identity, and particularly female identity. To me, many of her images seem to explore the struggle to fit in, an anxiety to reconcile conflicting parts of the self.

With its nostalgic, sepia-tinged colouring, Me and Virginia’s Doll may be softer and calmer than some of her other works, but the essence of her artistic perspective is clear. A self-taught artist who began taking pictures for fun at the age of 10, Destiny keeps a deliberately low-budget, low-tech look, taking Polaroids and later transferring them to laser, bubble or light jet prints. She doesn’t have a studio, but instead works out of her living room in her Brunswick home. And instead of models and fancy sets, her mise-en-scène is made up of friends and family members who she asks to pose with props selected from her collection of kitschy souvenirs, black dolls and golliwogs.

Her use of these dolls- which have long been considered controversial- brings a politically-charged element to her work. By appropriating images that she claims to ‘hate’ into beautiful, poignant new works, Destiny challenges stereotypes and misconceptions about Aboriginality. ‘I feel sorry for them and I think the dolls represent us in some way,’ she says. ‘I see myself as rescuing them from the people that would buy them. I’m saving them, adopting them.’ Taking these dolls, which so many people like herself find abhorrent, and giving them a new life in art is part of the challenge of her work. ‘You can sort of put your spirit into it, but you can’t make a doll smile,’ she says. That’s the trick with the photography, to create that mood for the doll and say something for us.’

I think her work is extremely beautiful and innovative- the way she can take everyday objects and imbue them with so much personality, beauty and even wit is really unique. And because it speaks across such broad social, cultural and political terrains, you can connect with it on a number of different levels. Destiny’s perspective as an Aboriginal woman is surely vastly different from my own, but the struggle to unite the conflicting pieces of the self and to find a place in the world is something we all share. And that’s why I think she’s amazing.

Beautiful!

Do you have a link or somewhere we can see her work?