celluloid relapse: strictly ballroom, wither australian cinema?

Imagine, just for a moment, that you are no longer you. You are an alien dumped unceremoniously upon this earth for no apparent reason. Unsurprisingly you feel quite alone, disoriented and encumbered by your flotilla of antennae. From here, how would you proceed? If you were in any way rational, it is likely that you would start with an appraisal of your immediate surroundings and continue from there.

Balzac, overtly descriptive as he is deceased, was fond of this path. Certainly, in his view, it is best to approach the world first by knowing your personal pocket of reality and then may you attempt to approach that frequented by others. Following this logic, individual titles in the Comédie Humaine generally commence with an assessment of a window frame, ceiling and other people present before branching out into the great unknown. Theoretically, we should follow a similar path with regards to cinema: Australian film as an entrée followed by a main plate of Weimar cinema, with a small Iranian dessert to conclude? Imagine my shock when I realised that despite the passage of months and of several columns I had failed to review my surroundings. Insofar, I have not discussed a single Australian film. Quelle horreur indeed! Mr. B would have been mortified.

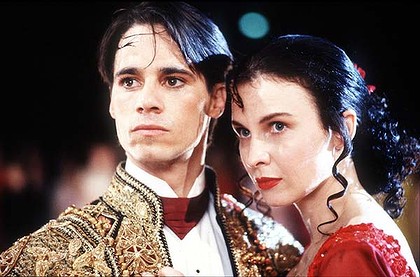

Strictly Ballroom (1992), shall I compare thee to a summer’s day? For one that despises the sun, thou art certainly lovelier, more entertaining and convenient in the absence of sunscreen. You feature a nice heaping of the crème de la crème of the Australian industry: Bill Hunter, his hairpiece, Baz Luhrmann and Barry Otto. Your plot of underdogs and less attractive people succeeding is one to which we are well accustomed, but is improved markedly with a ‘rogue dancer’ twist. Your inclusion of the Australian accent is a magnificent treat, as is your use of colour, conversation, dance scenes and character. Viewing Fran’s (Tara Morice) rise from bespeckled wannabe to ballroom queen brought a tear to my eye (despite its parallels with Grease (1978) vis à vis self modification) and Scott (Paul Mercurio) is sufficiently hunky. Strictly Ballroom certainly delivers; it ticks all the boxes of what makes a good Australian cult film. Take that Tina Sparkle.

Unfortunately, this ‘ticking of boxes’ and familiarity become somewhat bothersome. The size and reach of the Australian film industry and our propensity to recycle has seen us repeating – or at least attempting to repeat – similar ideas in similar formats. There’s usually an underdog, a bully, a weirdo, a Bill Hunter, a Sophie Lee or a Noah Taylor – or at least there used to be. Unlike the comparatively cosmopolitan British or Hollywood industry equivalents, the Australian film industry heavily emphasises our own talent and focuses on situations that couldn’t be anything but Australian. This is not necessarily condemnatory; this is a major part of their appeal for many people. An inherent Australian quirkiness undoubtedly resonates with its audience and appeals to foreign markets for its uniqueness, but it may also be quite limiting.

This inherent esoteric tendency may be what is keeping Australian film from consistently reaching the international mainstream audience it wishes and needs to access. In lieu of cold hard currency, no industry can rely interminably on government and social support. In the interests of self preservation, more financial success is required on a more reliable basis. After all, we live in a society governed by capitalist imperatives. Film may well be artistic expression, but it’s also just another way to make money.

Of late, the Australian film industry has appeared to have adapted itself more to this idea of creating more cosmopolitan film for a global market. Happy Feet (2006) with its star studded American cast, culturally ambiguous plot and location in the international no-man’s land that is Antarctica was an international success story. Its Australian origins were not overly perceptible.

The inverse is also true. An international proliferation and celebration of Australian film over the past few years, notably with the critical success of Samson and Delilah (2009) and Snowtown (2011), rejects this idea that a film must conform to Hollywood standards. Esoteric Australian film is simultaneously viable and untenable in the international context.

In international terms, our simultaneous existence within the cultural spectrum of the United States and exterior to it places strong exigencies upon our cultural industries. Faced with a choice of attempting to penetrate the US market or by simply catering to our own, some breed of strategy is required.

In any case, we should certainly not make any exceptions for our films at home, nor should we regard them under any special criteria. Judgement such as ‘it was good for an Australian film’ is not a valid qualification. It is inherently damaging to conclude that due to origin our film should be in any way inferior. So too is the type of thinking that led me to my aforementioned panic. Strictly Ballroom should be watched, adored and revisited regularly not because it is a good Australian film, but because it is a good film. It is essential viewing for every human, animal or alien – however unceremoniously displaced.