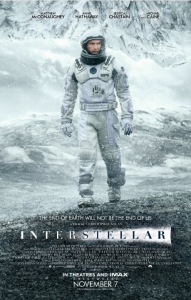

film review: interstellar

Christopher Nolan has to be one of the most polarising filmmakers of the modern age. Just start a conversation in the presence of “Caped Crusader” fans about his Batman Begins, The Dark Knight or The Dark Knight Rises, and watch the sparks start to fly: those who liked the films, those who didn’t like them…those who felt they were stapled much more stringently to the comic’s origins, those who thought they were all way too “real-world-grounded.” Then of course, you have all of the work that Nolan has done outside the scope of his Batman trilogy, with titles such as Insomnia, Memento, The Prestige and Inception coming and going under the proverbial theatrical radar.

Into this mix comes Nolan’s latest quasi-space opus Interstellar, a film that has been radiating quite the hubbub since its release, amongst die hard Nolan followers and general science fiction fans alike. Some critics – and casual filmgoers for that matter – are likening Interstellar to Stanley Kubrick’s masterpiece 2001: A Space Odyssey, calling Nolan’s new film a “2001 for the modern generation.”

Upon first analysis of Interstellar’s plot, it’s easy to draw parallels between Nolan’s vision and Kubrick’s A Space Odyssey: Interstellar tells the story of Earth in a not-too-distant future (a theme which has been explored in a plethora of films over the past few years à la Edge of Tomorrow, Oblivion and Elysium) that has been ravaged by an environmental disaster known as The Blight. Humanity has been forced to abandon technology and “the dreams of discovery” to focus on raw, basic survival, and former NASA pilot Cooper (Matthew McConaughey), now a widowed father of two, is tasked with growing one of the planet’s remaining sustainable crops: corn. The underlying narrative here suggests that mankind has put aside personal desire in the interest of a “greater good” – something Gene Roddenberry not-so-subtly explored in Star Trek – as Cooper finds peace tending to a new farm life to provide for his teenage children Tom (Timothee Chalamet) and Murph (Mackenzie Foy) as well as his father-in-law (John Lithgow).

Cooper is eventually reunited with a colleague from his past, Professor Brand (Michael Caine, a Nolan casting staple), and he’s suddenly informed that the situation on Earth is far worse than he thought. The former NASA pilot is asked to leave his family behind – in a world growing ever more unstable and danger-filled – to set out on an uncertain journey into the void of space. The mission? To find humankind a new planet to inhabit.

Perhaps the biggest question Nolan’s Interstellar asks is if we can be inspired enough to look skyward and wonder what’s beyond when most of us in this day and age are looking downward, transfixed by cell phones and tablets. And that, perhaps, is one of the larger comparison factors to take into consideration when discussing Interstellar and 2001: A Space Odyssey. Let’s not forget that Kubrick is largely regarded as one of the greatest (if not the greatest) filmmakers of all time, and Arthur C. Clarke was a bona-fide genius, who predicted everything from satellite internet to iPads to you-name-it. And while Nolan has his chops, he hardly lives up to the precedent set by Clarke and Kubrick. It hardly comes as a surprise, then, that some critics have likened Interstellar as a “comic book” to Kubrick’s “lyric poem” of 2001; but in contrast to 2001’s “man alone” underpinnings, Interstellar can be seen more as a family story at heart, with McConaughey’s Cooper character trying to do what’s right for his children.

Where Kubrick introduced science fiction fans to HAL, the computer system that would become something of a household name, Interstellar asks audiences to meet its own robot, which boasts a “variable sense of humour” setting. Yet it’s not until their third acts, respectively, that Interstellar and 2001 begin to align more closely in terms of comparison; in both films, the protagonists reach the end of their respective journeys. In A Space Odyssey, Bowman arrives at the third monolith near Jupiter and appears to be thrown through a cosmic portal to another galaxy. In Interstellar, Cooper is drawn into a black hole inside which an Escher-like architectural structure represents a single moment in time.

At the heart of Interstellar’s science is an element that suggests astronauts have found planets capable of sustaining life, and that just maybe Earth’s population can be moved through a traversable wormhole near Saturn, providing an expressway out of the galaxy and on to the infinite planets and stars beyond. As the crew members of Interstellar enter the distant passage, complete with an altered space-time continuum, they engage in a debate with one another in which they refer to theories advanced by Albert Einstein, Stephen Hawking and Kip Thorne (Thorne, a theoretical physicist and longtime friend of Hawking’s, served as an advisor and executive producer on the film). Indeed, the areas of black holes, relativity, singularity and the fifth dimension are explored by the characters and underlying narrative of Chris Nolan’s Interstellar.

Nolan finds a strong foundation on which to juxtapose personal desire and our place in the larger universe – as well as evolved levels of understanding we have yet to achieve – in Interstellar. But unlike his earlier works, Nolan’s passion is most apparent in the science that runs through this film like a proverbial thread, as well as the stark contrast between the space-time theories and characters that populate the story.

Hey, just letting you know that there is an error at the end of the sixth paragraph – Cooper’s daughter was named Murphy and was not played by Anne Hathaway (I don’t know the name of the actress).