film review: sleeping beauty

The original ‘sleeping beauty’ fell into a century long slumber at the prick of a spindle, and woke up at the kiss of a prince. In Julia Leigh’s version a young woman surrenders herself to chemical sleep at the whim of a string of high paying elderly men.

Sleeping Beauty is the story of Lucy (Emily Browning), a quietly troubled, self sufficient young woman who survives by using whatever methods she can. Her mother who is an absent alcoholic, and her only friend – the reclusive “Birdman” are both dependent on her financially and emotionally. This responsibility fuels an understated recklessness in Lucy, which consequently leads her to become employed as a lingerie waitress.

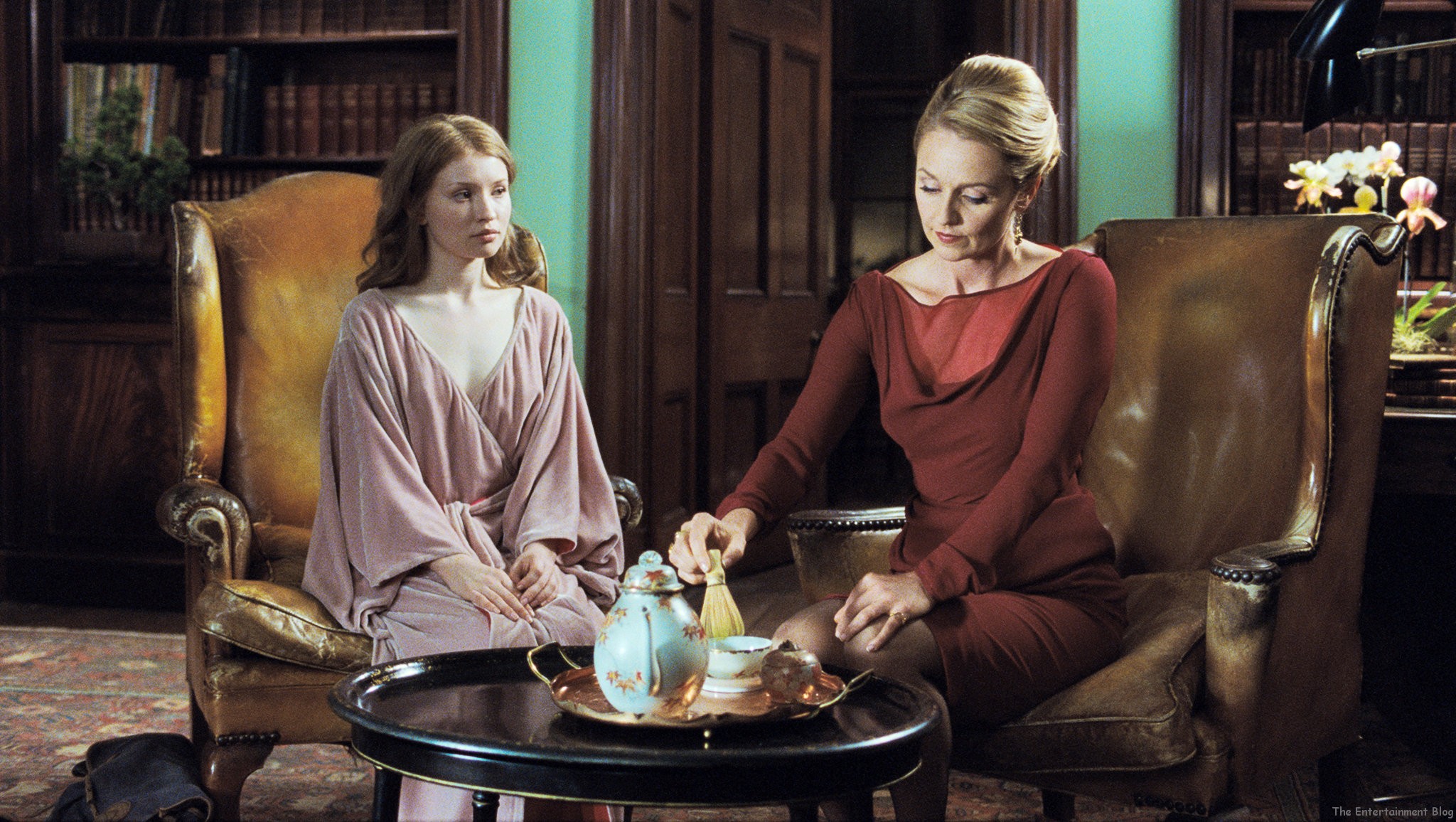

Already alienated from her peers, the further Lucy distances herself from her ordinary world, the more she becomes involved in her new job. After her short time as a waitress for groups of grey haired, tuxedoed dinner guests, Lucy falls into the position of a ‘sleeping beauty’. In this role she is given a sleep inducing tea and is laid naked on a bed where old men have their way with her unconscious body. The men we see visiting her play out fantasies of their own masculinity, with Lucy’s naked body as their only witness. Each man admires her sleeping form, but is ultimately more concerned with his own inability to perform various masculine acts. Penetration is forbidden.

Sleeping Beauty is a story told in minutia. There are the trappings of Lucy’s day-to-day world: a Campos coffee cup left on a desk, the blue vinyl of CityRail seats which become powerfully familiar beside the film’s fairytale portrayal of the sex-work industry. There are little signals for the transition from one world to the other. Lucy arrives at her first night as a lingerie waitress dressed in a hooded velvet cloak. In the dining room, a screen on a wall shows a naked female torso moving subtly in the background like a magic mirror. The film is visually decisive and thematically rich. Each scene is perfectly framed. The sleeping scenes feel like paintings. You could imagine Lucy had been lying there for 100 years.

This film takes a while to warm up. The dialogue is sparse and the audience is given little chance to relate to Browning’s character as she pouts through each scene. Despite the stripped back quality of the film, the real world could have been more natural. The seamless opulence of the manor houses and dining rooms are jarring, and doesn’t offer anything new. Even to the quietly disturbing end, the madam of the ‘sleeping beauties’ remains relatively impenetrable. However, the film does gain momentum. Lucy’s character rounds out bit by bit. Eventually there’s a rhythm to the transitions between one world and the other, which manages to propel the story to its conclusion.

Sleeping Beauty is a visually engaging piece of cinema. However, the characters and settings could have been more imaginative, more compelling. Leaving the cinema should have felt like waking from a beautiful dream. As it is, it felt as though those hours had never existed.