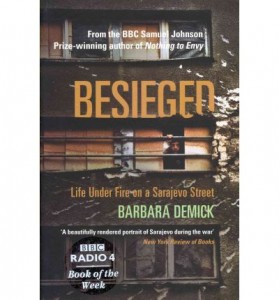

lip lit: besieged

Barbara Demick tells the stories of those locked in to an unyielding series of bombings and sniper attacks in Besieged.

I first became aware of Demick’s work through reading her award-winning Nothing to Envy. She provided an amazing and rare insight into the lives of North Koreans. I was excited to learn of her new offering, the inside story of the Sarajevo siege, though it is not a wholly new. A book by Demick called Logavina Street was released in the 90s after she had covered the seige as a journalist. Besieged is the title of a new, edited edition of that book.

I was too young to remember the Sarajevo siege of 1992-96. I remember echoes of the word ‘Bosnia’ in a BBC foreign correspondent accent, and so I should as many great correspondents got their start reporting on the seige. As a U2 fan, my first cognisant introduction to it was in their song “Miss Sarajevo”, where the band was accompanied by the bold vocals of Luciano Pavarotti. The song is odd and vaguely mesmerising. After listening to it I sourced the internet for more information: Sarajevo is the largest city and capital of a nation now known as Bosnia and Herzegovina (thanks to Eurovision, I’m able to pronounce the name). It is historically multi-religious and diverse and happily so. During the break-up of the USSR, lots of nation-states were battling for independence. Bosnia declared independence from Yugoslavia. Sarajevo went under siege first from the Yugoslavia People’s Army and later by Bosnian Serb forces which wanted to create an ethnically Serbian state. ‘The beautiful city of Sarajevo, with its mosques, synagogues, Orthodox and Catholic churches, was besieged for three and a half years, its food and electricity supplies cut off, its civilian population relentlessly bombarded.’

There was a huge number of civilian causalities with nearly 10,000 estimated deaths and a further 56,000 wounded.

The siege was discriminatory in nature. Although everyone in Sarajevo – regardless of religion – was under threat, the opposing forces wanted to create a purely Bosnian Serb state with no Muslims. Nobody in Sarajevo really understood this desire, neighbours of different religions tended to get along very well, interfaith marriages were particularly common, ‘Muslims visited their Catholic friend for Christmas, dinner, and celebrated Christmas again with their Orthodox friends in early January. For Bajram, the most important Muslim holiday, Muslims hosted their Christian friends and neighbours.’

The opening scene of the book describes a mortar shell hitting a local marketplace, resulting in the death of 68 people. Demick writes, ‘after 22 months of siege, it was just another in succession of very, very bad days.’ Reading the book does not get any easier from there onwards. People die, weaponry invades their homes, nowhere is safe. This book has an overwhelming collection of stories of people’s deaths and injuries. It’s like watching the television after September 11 or major disasters, it’s helplessly upsetting.

It’s not just the deaths that are upsetting, it’s also the new lifestyle of those trapped in Sarajevo. One woman, Delia, gets a signal from a TV station in Belgrade on her small car-battery operated television. She sees an ad for pizza while she is forced to live off UN rations originally made for the Vietnam War. In the day time, it’s dangerous to go outside as you become an instant target for snipers and bombs. At night, the city is pitch black with no electricity for street lights and mandated curfews. Entire families find themselves cornered into the safest rooms of their houses – away from windows or into bomb shelters. It’s claustrophobic. The city had previously hosted the 1984 Winter Olympics and was filled with a cosmopolitan population who enjoyed travelling but who were trapped and cut off. The siege marked a devastating loss of life as well as a loss of dignity.

To make matters worse, few people thought that the siege was going to happen anyway. Sure, there may have been threats but it was the 90s, surely we were beyond waging wars against innocent citizens? Surely, modern civilisation was past that?

So often, history gets told in a dehumanised way. “Great Britain disagreed with the United States”, “France did X”, “China did Y”, etc. The problem is that states aren’t people, statistics aren’t people, yet people are right in the middle of warfare and policy decisions. Demick’s journalism, both in this book as well as in Nothing to Envy has been important because it’s not about bombs being dropped in a place and a meaningless number representing the deed. So many people were affected by the Sarajevo siege and each scene in the book is a powerful reminder of the real human face of political and ideological conflict.

The humanising strength of this book is also what makes the book difficult to read. There are 250 pages of devastation that Demick has provided. It’s valuable and important but overwhelming nonetheless.

Besieged is published by Granta.