lip lit: one life: my mother’s story

The woman behind the counter jiggles the baby on her hip. The child is red-faced and crying. Customers smile sympathetically as the woman tries to serve them and placate him. She had no choice in the matter. The daycare is closed today. There is no one at home who can care for her son. Thus he is at work with her. And he is hungry.

This may seem a somewhat less common sight in today’s world of long-hours daycare, but women’s battle between work and family goes on.

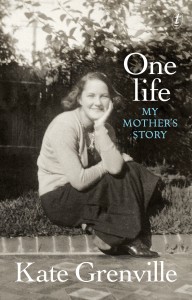

In her new work of nonfiction, One Life: My Mother’s Story, bestselling author Kate Grenville paints a sensitive and, at times, painful picture of her own mother, Nance Russell. Leading from Nance’s ‘fragmants of a memoir, the work is more than just a recount of one woman’s struggle against the conventions of twentieth century Australia. Throughout the layers of Grenville’s book we discover the story of a woman whose life was influenced significantly by the relationships she had with those around her.

Readers are quickly introduced to Nance’s family relationships: the harshness of her mother, Dolly, and Nance’s disrupted childhood, which saw a family who owned pubs and hotels across New South Wales move frequently. The additional dislocation Nance experienced as a child boarding in various schools across the state left her with a deep sense of longing for family. Grenville describes how her mother thought, ‘On my deathbed I’ll still be longing.’

She struggles with the distance that developed between herself and her older brother, Frank when, as children, they had been inseparable. Both of Nance’s brothers go to fight in WW2. Frank is caught and kept in a Japanese POW camp in Java, where he dies. Nance and her family only find out after the war. Grenville paints a picture of her mother taking a long time to get past this loss, as she also mourned the loss of an opportunity to reconnect with Frank.

The other key relationship of the book is between Nance and her husband. She finds herself in an amicable but loveless marriage to Ken Gee, a lawyer and, as it turns out, a Trotskyist who wrangles out of fighting in a war both her brothers are fighting in. Nance knows that Ken admires her, but love is something else.

Grenville’s depiction of her parents’ marriage is pragmatic – as pragmatic as a writer can be when writing about loved ones. Nance is depicted as settling into a sort of companionship with Ken, although confusion remains about whose fault it is that her marriage is loveless. As it turns out though, both Nance and Ken have respective extramarital affairs throughout the duration of their marriage.

Nance’s relationships with her children drives the latter part of the book. Moving into motherhood, she experiences the loss of independence briefly when she leaves the workforce. However, the joy of the ‘bond more profound than anything she could have imagined’ of motherhood takes over as she cares for her two sons – Grenville’s older brothers.

And it is this relationship with her children which seems to divide Nance’s loyalty when it comes to her career.

‘When you’re a woman, she thought, you can do everything. Just not all at the same time.’ Nance’s thoughts on the eternal division and the pain that comes with attempting to divide one’s time between one’s children and one’s job rings all too familiar, even today. Especially today.

Nance puts her children into an early form of daycare while she returns to her work as a Registered Pharmacist, primarily to save money for a house which she then helps build. She heroically winds her way between the bureaucratic red tape and social biases to establish her own pharmacy on Sydney’s Northern Beaches, only to have to sell it again when she is unable to find sufficient childcare for her young sons.

Grenville is skilfully objective in the depiction of her mother’s struggle between work and family. There is no judgment and no pity but rather a gentle sympathy in her portrayal of a difficulty which women continue to face.

Interestingly, Nance was drawn to pharmacy since, unlike a teacher, she got paid the same as a man in the same job and could continue working after she got married. However, her career seems to have been simultaneously a triumph and a burden for her. Grenville describes how her mother had ‘qualified herself out of a job’ as she made the leap from an apprentice (on an apprentice’s salary) to a fully fledged pharmacist – in the middle of the Great Depression.

Grenville’s work is recounted in a strictly chronological manner, which has the advantage of narrating the history of a nation and its women while telling the story of one woman in particular.

The changing manner of women’s rights throughout the past one hundred years is carefully interwoven through Nance’s tale. For example, when reading her university results pinned to the board, Nance notes, ‘X denotes female student. The women were all Miss, where the men just had their initials.’ The distinction is there and Grenville incorporates her mother’s thoughts on each matter, without the assumption that they reflect the thoughts of all women from Nance’s generation; a generation whose lives were so different to those of any who have followed since.

Ultimately, this work is a very brave and loving recount of a daughter’s view of her mother’s history. ‘Thinking about your mother as a woman, with a private inner life, is daunting’, Grenville concludes. But, despite any misgivings she may have had, she has produced a powerful piece of nonfiction, important equally for its capacity to capture one life as its ability to summarise that of an entire generation of women.