#ELLEfeminism: who is feminism being rebranded for?

When Elle announced their campaign to “rebrand” feminism, it was met with mixed feelings. Many expressed gratification and pleasant surprise that such a high-profile magazine should deign to take notice of a little old campaign for gender equality like feminism, taking the view that the only thing better than publicity is free publicity on a global scale. Many others, however, had concerns that the principles of a consumerist publication that is at least instrumentally responsible for many of the problems feminism has sought to overcome are fundamentally incompatible with the movement. A similar campaign, run by Vitamin Water, also sought to change the image of feminism and make it ‘relevant and meaningful to everyone’, in exchange for a $2000 cash prize. The winning entry was the less-than-radical slogan ‘Feminism Is Human Rights’ – made somewhat weak-sounding by the extra clarification that to not believe in those rights is your right as well.

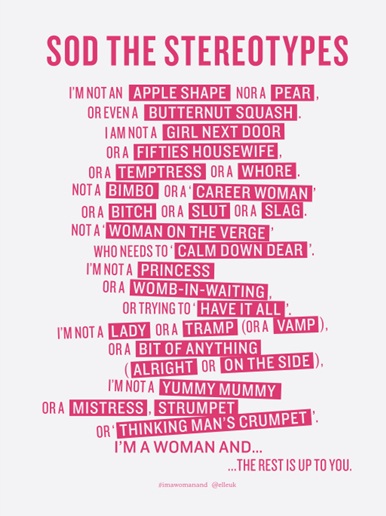

These endeavours come at a time where a hot topic in breezy mainstream feminism is how far one can creep back down the path of conventional and accepted femininity and still “be a feminist”, as if the prime intention of feminism was to prevent women from expressing themselves. Not a day seems to go by when an article such as the Guardian’s ‘Can You Be A Feminist With A Boob Job? I Am’ gets published. Natasha Walter’s recently published book The New Feminist explores and discusses questions such as ‘Can a woman have rape fantasies and be a feminist?’ and ‘Can a woman have a white wedding and be a feminist?’ Popular woman-orientated websites such as Vagenda and Jezebel dedicate considerable virtual column inches to tackling similar issues. We are told that Sheryl Sandberg is the new face of feminism, or Hillary Clinton, or Caitlin Moran. Even Margaret Thatcher, hardly known for her keen sense of social justice, has been touted as some kind of feminist icon. Feminism, we are told, is for anybody. But should it be?

While it may be more appealing to have a definition of feminism that is so all-encompassing it can be applied to almost anybody with a vague interest in gender equality, an inevitable result is that the movement is diluted almost beyond recognition. In her book Feminism is for Everybody, bell hooks wrote that ‘lifestyle feminism ushered in the notion that there could be as many versions of feminism as there were women… suddenly the politics was being slowly removed from feminism’. With their all-too-similar hashtag #feminismisforeveryone, Elle not only embraces “lifestyle feminism” and encourages the idea that all one must do to be a feminist is write it in your Twitter bio, but do so in the knowledge that broadening the boundaries between feminists and non-feminists enables them to take the label of “feminist” whilst leaving behind the hard work and attitudes that should come along with it.

Their so-called rebranding of feminism is directed at a very specific subset of people: those to whom the recent upsurge in white middle-class neo-liberal feminism appeals. Feminism has made a dent in the world of popular culture in recent years, but only in forms that we are already used to seeing. By this I mean Caitlin Moran’s How To Be A Woman, the rise of young pre-feminist Lorde and Lily Allen’s recent single Hard Out Here, to name a few very recent examples. These projections of feminism seem radical by comparison to the mainstream of a sexist society, but on closer inspection only really serve those who are already in well-off positions within the status quo – that is to say, are almost entirely white, well-off, Western, straight and cisgender. The concept of intersectionality has been written off by these feminists as simply too difficult to incorporate into their version of feminism, with the silent implication that since it is hard to sell to the privileged, it’s not worth bothering with. The word “sell” is key here – rather than accept that those with high degrees of privilege do not necessarily take precedence within the feminist movement, the effort to “rebrand” feminism takes the far easier and less challenging route of rubbing off the hard edges and making feminism something that looks good on a magazine cover instead of a movement to amplify the voices of the underrepresented.

This version of feminism that Elle is peddling, in which the concept can be neatly packaged up and used as a marketing ploy, does nothing but sell its November issue. Taking the weak surface-level feminism that has made its way up to the top of popular media and using it as the basis on which to base your feminism is the equivalent of judging the entirety of today’s music by what has eked through to the Top 40 at any given time. Broad acceptance and popularity does not necessarily equal quality, and this goes double for social justice movements that are actively going against the grain. The problem here is not that Elle are inherently evil or that the points they raised in their debate are not relevant, but rather than feminism does not belong in the world of capitalism at all.

A feminism that aligns itself with the direct oppression of women who are not in positions of privilege cannot reasonably consider itself feminism, and the efforts to do so both miss the point of what feminism should be and bypass the need to engage in criticism of the damage capitalist feminism does. Talking about how femininity is not un-feminist may be an important sentiment to get across to the readers of a fashion magazine, but when those ideas are scattered between pages of super-thin models wearing clothes made in sweatshops by women elsewhere, they hold little feminist clout. Identifying as a feminist is a learning process in which Elle have skipped one too many steps. Their feminism, in all its efforts to be for everybody, is so far removed from the lives of women globally that it ceases to truly be for anybody at all.

This is a great article! When I attended a young women’s leadership program a few years ago I was surprised that I was the odd one out as I did not want to rebrand feminism with a more ‘approachable’ label. Ironic that women should change feminism to make it more palatable for the ‘mainstream’.