meet the winners of the 2017 rachel funari prize for fiction: 3rd place, “aftermath” by alice bishop

Alice Bishop was awarded third place in the 2017 Rachel Funari Prize for Fiction for her story, ‘Aftermath’. (Photo: Supplied)

Alice Bishop’s story, Aftermath, won 3rd place in the 2017 Rachel Funari Prize for Fiction. Here’s a Q&A with Alice, plus her award-winning story!

*

Tell us a bit about yourself. Who are you?

I grew up in Christmas Hills and now live in the city – working in digital communications during the week and writing when I can: short fiction mostly, but sometimes essays as well.

What do you think it takes to win an award-winning story?

I reckon it all depends on the judges’ tastes and the themes and what’s going on in the world at the time (and how all this relates to the work). That’s why you have to just write what you’re passionate about (cliché, I know, but important) and maybe just hope you can make the reader really feel something. The rest can be out of your control.

Where do you write?

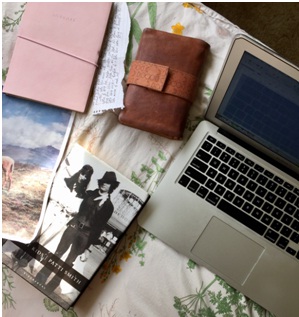

Mostly on my computer but sometimes, while I’m driving away from the city, in my head. I wish I wrote on paper more, though. There’s something really special about that. I loved seeing Patti Smith’s handwritten notes in Just Kids (I keep a copy beside the bed). She’s such inspiration to keep writing, to keep taking notice. It’s also good to have access to Wikipedia, snacks and sun.

Alice’s writing space (Image: Supplied)

What inspires your work? Particularly, what inspired you to write Aftermath?

Our house burned down, a while ago now, and writing has been a way of unpacking everything – especially when so many stories after natural disaster remain untold (especially the quieter stories, which aren’t necessarily less powerful). I’m also inspired by other writers, ones I look up to and hope to one day be half as good as: Josephine Rowe, Nayyirah Waheed, Steinbeck, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Junot, Deborah Levy – the list goes on!

Let’s talk books. What’s the last book you read? What are you currently reading? And what’s on your TBR pile?

I recently read Insomniac City by Bill Hayes and it is actually everything – a beautiful piece of writing (with really brill photos too). For what I’m looking forward to reading: Tony Birch’s new collection, Jennifer Down’s new collection, more Lucia Berlin and anything Laura Stortenbeker publishes (I can’t wait). Gratitude in Low Voices by Dawit Gebremichael Habte is on my list too.

Why did you enter the Rachel Funari Prize for Fiction?

These kinds of prizes are beacons of hope for emerging writers, I think, especially when arts funding is really rocky at the moment. Also, I worked towards the Funari Prize, using it as a deadline for just getting the story I was working on finished. And, though I never got to meet Rachel Funari I’ve only heard and read really beautiful things about her.

What does ‘Rebirth’ mean to you?

Nayyirah Waheed sums it up perfectly, I think:

‘she asked / “you are in love / what does love look like / to which i replied / “like everything i’ve ever lost / come back to me.”’

Aftermath

Silt and grit and cinders—these are the things I wash from my baby’s hair at my sister’s place: After it all. Only hours have passed since the fire and we’re in water again, bath-bound this time—already trying to forget that dappled glow: the sky above us catching light. My ears still hiss with the remnants of that deafening crackle: the sound made by a whole hillside of eucalypt leaves, curling with heat. The small, untouched floral jars of cream—stacked in my sister’s cabinet—show me she is still not happy, that she is still trying to smooth herself into something she’ll never be. My baby makes a small noise, something between a sigh and a hiccup, and I think of our rented bathroom cupboard, filled with things now burned: a pale-pink plastic toothbrush, some cotton balls, a blue coral ring.

Interviewer: How long did you shelter in the dam before the fire rolled over, before your neighbour—a true Aussie hero some might say—discovered you and your little girl?

Interviewee:

The tap dribbles cool water over my wide, sun-pink knees. I pause when the water pressure stalls—creating a low droning creak. A small wave of residual panic pulls at forgotten parts of me before my daughter and I are back in that dam—the fire about to roar over us like an aeroplane landing, like the magnified sound of an aerosol can catching light. My throat narrows, then my lungs bloom, before I regather enough to promise my baby her favourite for dinner. Blueberry pancakes, Elk-Elkie? I ask in a soft voice, not unlike the one I comforted her with in that clay-coloured water—just a few white-noise-warm hours before.

Home? My baby—still alive and still breathing—almost squeaks like it might be a question, though I’m not quite sure. She faces me in the bath; the whites of her eyes widened and still slightly pink from smoke. Her tiny eighteen-month-old hands, fleshy and perfect, cocoon my thumbs. The fresh water is cool and clean, comforting—nothing like the dam water that saved us, smelling of pond and a little of dark, rain-soaked earth.

Safe enough now, but uneasy in valley suburbs—built by ordered redbrick—I pull my baby out of the cool town water, and up onto my still singlet-covered chest. There’s a comfort to having her close; in her breath I can still hear what it was like before. Despite the surprise of our visit, I imagine my sister through the bathroom wall, restlessly tapping her small neat nails on kitchen granite. She has what people would call A Nice House; she buys lifestyle magazines filled with pictures of bearded lumberjack types—walking photo-shoot paddocks, flaxen, alongside wool-clad wives.

Tracey, this twig-limbed sister, is happy in her unhappiness; she sees the lingering weight as a sign she’s motivated to do better: pay more for softer hair; eat less for smaller clothes; live quietly for unlined skin. The world has pushed my sister to measure her worth by these things

Interviewer: Many die when they seek shelter in dams / tanks—known, often, by authorities as ‘death traps’. Tell us your message, as a surviving mother who may have—potentially—made a fatal mistake?

Interviewee:

Although I wish it were muffled, my mother’s sandy voice finds a way to squeak through cracks in the bathroom door. Her already cracking tone has risen: It just doesn’t seem real, Trace she says, then: They could have burned too. It will be weeks before I can wash the earthy smell of silt from my baby’s hair, along with the sharp tang of chemical ash: seemingly soaked into skin. Rowena! My mother yells this time, piercing and a little too much like a shriek: Are you ok in there?My baby’s tiny hands are now in smaller fists. The backs of them are turning blotchy and white. Her short eyelashes, thick, are still wet and stuck together in clumps.

We’re ok, I whisper then repeat. We’re ok—hey?

~

Grey flecks whir about us, the air conditioner vents pumping hot air and remnants of ash, as we drive to IGA, oddly as usual—for milk, for bread. My pearl-lidded sister, serious, looks at my bath-freshened baby in the rearview mirror like she, too, is now nothing but news. I think of my sister’s perfectly paled soaps, smelling of lemon and, now, a little of soot. I think of her wardrobes of neatly folded bed linen and her drawers of matching underwear—lacey and white but still sensible: not small. I watch a firefighting helicopter my sister’s Jeep window. Hours late to the scene, it hovers over the already burned ranges above us as the weather—still oven-hot and blowing—finally begins to finally break.

Rowena? My sister asks, interrupting my thoughts from her spot behind the wheel. Her tone is sharp, demanding an answer this time: Has the media called? Mum cuts in from the passenger seat—saying something about getting more blueberries, then about the baby’s strength and how she needs to eat. I feel something like love for my mother at that moment—with her silver-flecked hair secured, somehow, in a loose knot on her head. For my sister, I wonder what would have to happen for her to go without eye shadow. Even if hospital-bound and burned—her hands wrapped in gauze and sticky Vaseline—my sister Tracey would still somehow be pearled.

What do you mean, Tracey: the media calling? I ask from my quiet place in the back seat, not really wanting an answer. My baby stays quiet on my lap, her lashes still damp.

Interviewer: Can we talk about your husband?

Interviewee:

As we step out into the valley supermarket car park the helicopter leaves the ridge behind us and disappears over the mountain—towards the city where it usually sits: shiny, sleeping. With the hum of its blades fading I feel my baby calm in my arms. Heavy drops of rain begin to splash darkness into the footpath about us. You need to be heard, Rowie, my sister continues—pulling her green bags from the car. I am surprised she is so particular, at a time like this. She continues: An interview is good professional experience, and—with everything gone—you’re definitely going to have to find work. My sister Tracey actually says this, her eyes shimmering as she waits to see me flinch.

But something has softened in me; I stay quiet like my baby, her hair still smelling of silt: damp and musty, with a hint of my sister’s jojoba shampoo. As we walk across the empty carpark a tied-up dog begins to howl—its owners likely fled to the city, or to the oval Red Cross tent for paper cups of warm water and false but comforting hope. Poor animal, my sister says as my baby sneezes, the sound another welcome reminder that she is still here—still breathing. This smell of burned things is not a friendly smell—not like childhood bonfires or Sunday toast, blackened and scraped; there’s harshness to the air about us. My baby looks up at me, the scratches on her face the same maroon colour of the old now-burned hatchback—left behind at our disappeared house.

It’s all ok, hey Elk? I say, smiling down at my small daughter. She almost smiles back, but stops and I feel the heavy fog that follows panic—lacing the abandoned valley street.

~

Quieter than she’s ever been, my baby—puffy limbed and perfect—clung to my dam water-stained shirt as we walked from the water, ash still falling about us in gum leaf-sized flakes. Hours, days, years: I couldn’t then have said how long we’d been in the water—huddled, like animals ourselves, hiding from heat.I’m coming for you! A short man yelled through the reeds, seemingly appearing from nowhere—his sun-marked cheeks shining with sweat, maybe tears. Still copper-coloured from flame, the sky about his shoulders made him glow. I knew it was evening. And not because of the man and how he offered us a ride, but because I was talking to someone, conversing, I knew—then—that we were still alive.

Radio warnings hummed through the ute as this man drove me to Tracey’s house—the only place I could think of going, despite hoping for somewhere else. Still teary, he wore a thick woolen jumper and dirty white cricket shorts. Punctuated by coughs and steely gasps, the man—now driving the bushfire-blackened bitumen—spoke too quickly of his apple orchard, burned, and told me that the CFA, though sorry, had turned up late. Look at my arms, he said, a little too abruptly, and so I did: at the blisters beginning to bubble and at the wire marks, burnt into now too-smooth and oddly shiny skin.

We’re lucky hey? I said, perhaps trying to convince the both of us; the smell of singed hair and something like tinfoil, microwave sparked, lingering on him.

Interviewer: What did you find in the ashes? Any jewelry? Photos? For our audience now, what would you take with you—if you got another chance?

Interviewee:

Salt-laced cheeks, softening bottles of Mount Franklin, my baby’s small shorts darkening with fear: This is what I remember of fleeing, the house, and what people will refer to later (in voices, hushed) as Everything: Gone. But too many stayed behind by houses, only to lie down, smoke choked, alongside garden hoses—warm and limp. I could tell my sister Tracey this, but she would only pretend to listen. Only days will pass since the fire before she’ll mention the loaned DVD set, casually—her voice smiling semi-sympathetically through my borrowed Nokia phone: Did I lend you any box sets, sis? She’ll ask. Then, Mum’s silk wedding dress—you also had that yeah?

It’s hard to check, Tracey, I might say,thinking of the photos I’d neatly filed of newborn Elkie, her tiny face pink and squished, I mean I would go look Trace but—remember—it all burned.

A small sigh will whir through the phone. Oh Rowie, my sister will say, then pausing heavily for emphasis: I’m not upset—just keeping track of what I’ve lost, you know, too.

Interviewer: I hear you lost a dog, along with everything else? What advice do you have for the pet lovers watching, now?

Interviewee:

On the way into the television studio my sister preens me—offering me lip-gloss, thick and glassy, while brushing unseen things from my borrowed shirt. My baby stays clipped to my side—something like a souvenir clip koala—as we walk backstage. There are trays of disposable cups filled with ice water and boxes of donuts, the fancy kind with icing the colours of earth. My baby clings tighter as we pass a curly haired man in a lanyard and headphones, along with two white women, laughing about something in their sprayed-terracotta skin.

We’re ok, I whisper then repeat, my baby’s eyes fluttering with near sleep. We’re ok—hey?

~

Studio lights beat down on me, making the sweat rise in beads across my heavily made-up upper lip; my sister has made sure my freckly skin is thoroughly covered in department store foundation, thick as dam-floor clay. The interviewer is wearing small silver heels, strappy enough to show white-painted toenails. Her name is Bianca, even I know that; she smiles tight from the TV: ads for milk-coloured vitamins and under-eye cream.

I remember that day so well, Bianca, the interviewer, is telling me before we start—her voice low and reflective. However, her face doesn’t move much and veins, aubergine, pop out along her wrists. Everyone remembers what they were doing the day of the fire.

An assistant comes to brush something over my cheeks. I can’t see my baby from the stage, but a row of black cameras—lenses glinting in semi-fluorescent light. Victoria’s Darkest Day, the interviewer continues. We were all so shocked and so scared.

Yes, I try to say—though I am frozen in my chair and no words are leaving my mouth. Yes, I try to say though all I want to do is stand up and say, No, Bianca. Then, No, not really—it was just silt and grit and cinders; not everyone was there.

Twitter: @BishopAlice

Instagram: @alicebishop

Facebook: /alicebshp

Congratulations Alice! I love your writing, such powerful images.