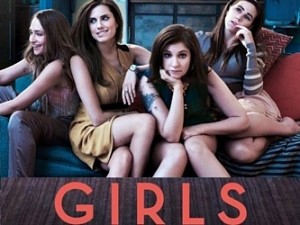

small screen sirens: girls

**Spoiler Alert : If you haven’t seen Girls yet, maybe don’t read this unless you don’t mind spoilers!**

‘Rich girls in the big city’ has proven a tried and true format on television, especially in the last few years. From Sex & the City through to Gossip Girl it feels like we, as a western, developed society just can’t get enough of glamorous women fucking up and fucking around in the big apple. This year, HBO premiered Girls, a shiny new half-hour series dealing with a similar theme, a quartet of privileged young women living hard in New York. Created, written-by, frequently directed by young auteur, Lena Dunham.

Dunham also stars as Hannah, a young writer living with her best friend, Marnie, and in a tumultuous and unhealthy relationship with aspiring actor, Adam. She’s tattooed, talented and funny, but prone to intense fixations and general uselessness, both of which manifest further upon the news that she’s just been cut off from her parents who had previously been supporting her financially. Marnie, Hannah’s flatmate, is beautiful, works in a gallery and is in a stagnating relationship with her clingy, puppyish college boyfriend, Charlie. Meanwhile, their friend from college, Jessa, is back in town, pregnant and generally spiralling and living with her neurotic, virginal cousin, Shoshanna. The series deals almost exclusively in taboos like abortion parties, shotgun weddings, obscure sexual fantasies, hitting on your boss and just how much you should write about a friend and their mistakes when trying to become a professional writer. From episode one, this was a different animal to Sex & the City, in spite of numerous references to its predecessor.

I’ve been wracking my brain trying to think of why Girls feels so damn different from everything else on TV right now, and the answer came to me by surprise, because it’s a show that doesn’t ask you to like its characters, doesn’t ask you to even seriously empathise. Instead it just relies on the knowledge that whilst you might not be able to understand Hannah’s ability to simultaneously take her relationship with Adam too seriously and not seriously enough, or Jess’s reluctance to get an abortion which ends in a miscarriage that she’s far too happy with, someone, somewhere out there, can. It doesn’t cater to the everyman, doesn’t try to please every audience, and instead owns its mistakes like its characters do, because the girls’ decisions, fuck-ups and triumphs are just that – theirs to make.

One of my favourite storylines of the series is Shoshanna’s; on-edge, prone to fits of extreme neuroses which includes giving non-sexual groin massages, accidentally smoking crack and bringing candy snacks to an abortion, she’s pursuing losing her virginity as aggressively as her anxiety allows. The whole thing culminates in the finale, where she and hilarious season regular, Ray, a friend of Charlie’s and Hannah’s, get together. What results is this sort of horribly awkward and tender moment of rambling, obscure declarations with Shoshanna setting aside insecurities and throwing herself into a moment with a man she barely knows and yet there’s no shame associated with this. The show doesn’t patronise Shoshanna’s choice or criticise her sexuality. Like everything else on the show, whatever happens happens.

I think that’s the thing about Girls though, about why it works. Everyone I know who’s seen it has a moment where they cringe and gasp and everyone I know has a moment where they say that is so me. The greatest flaw of each of the characters is that they’re people, that they’re selfish and conceited and that their problems are bigger than everyone else’s.

That said, no one punishes the girls of Girls more than they punish themselves, but no one forgives as quickly or unquestionably either. Hannah, Jess, Marnie and Shoshanna are each heavily flawed characters, wealthy, white and supported, but their problems are real and universal. More so than anything, it’s a show about carving out an identity as a small woman in a big city, full of voices just as eccentric, just as damaged and just as insecure, and that in itself is a story worth relating to.

Image Credit