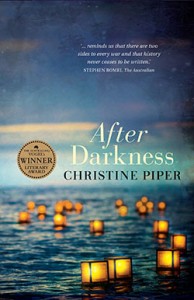

lip lit: after darkness

As the train lurched forward, the woman grabbed her daughter’s hand and dragged her towards our carriage. She came so close I could see a mole above her lip. She spat. A glob landed on the window in front of my face. ‘Bloody Japs!’ she said, shaking her fist.

After Darkness draws the reader into a world of violence, racism and intimate tragedy. Set in the midst of World War Two, After Darkness tells the story of a Japanese man arrested in Broome and sent to the isolated Loveday internment camp in South Australia. As this narrative unfolds, the reader learns more of Doctor Tomokazu Ibaraki and his journey from Japan to Broome before the outbreak of war.

It is difficult to read about how white Australians treated the Japanese at this time, particularly given the peaceful (if largely segregated in Broome) coexistence that is shown in flashbacks throughout the novel. But that painful self-awareness is what makes this book fascinating and important; if you’re not aware of your history, you are doomed to repeat it. Learning the degree of Australia’s involvement in the war through a fictionalised account of an ‘outsider’s’ experience is harrowing but more compelling for someone, like me, wary of traditional military narratives of mateship and national pride.

After Darkness won The Australian/VOGEL’s Literary Award in 2014. It is a richly deserved win for first time novelist, Christine Piper. Although the novel is fiction, Piper consulted military records at the National Archives and the Australian War memorial. She also conducted interviews with former internees and their relatives, and delved into Japanese history from the perspective of Japanese historians. The effort is apparent through the text and serves to deepen the narrative. The settings are richly drawn, allowing the reader to understand not only Ibaraki’s motives, but those driving the men around him.

It is hard to not relate the harshness of the treatment of the interned ‘aliens’ with the current attitude towards refugees in Australia. Though Australia was at war with Japan, the majority of those arrested were removed from their homeland both politically and emotionally. All of the men are held without access to information, fed sparsely, and left to occupy themselves. Despair is hard to avoid, and the narrator watches helplessly as his fellow inmates succumb to depression and self-harm. The lack of empathy from the captors, fuelled by jingoistic ‘othering’ leads to a devastating final act.

The violence of authority is all too familiar, and one can’t help but wonder if our grandchildren will read books based on Christmas Island or Nauru with such shame and sadness.

There are elements of After Darkness that would have benefitted from more exploration. Ibaraki’s wife Kayoko is introduced as a complicated and intriguing character, but her story is quickly overwhelmed by Ibaraki’s gruelling work in Japan, and she fades into obscurity. While I understand that this is mimetic of her own experience, it is disappointing. Similarly, the nun that Ibaraki works with in Broome has the glimmer of personality but is cast aside before any real character development.

Overall, it should be read as a compliment to Piper’s work that I wanted more of it; the final few pages tease at an ongoing story I wish would be told. This story of a man in limbo between two worlds is beautifully rendered and is a valuable contribution to our literary landscape. When accepting the Vogel, Piper said that ‘In many ways, modern Australia is built on immigrant’s tales’.

After Darkness is published by Allen & Unwin and is available now. It is Christine Piper’s first novel.