a cultural shift: killing off TV snobbery

Upon discovering that Kevin Spacey and David Fincher are working on a new production, it would be natural to assume the project from the director of Fight Club is a big budget film. Wrong. House of Cards explores betrayal in US politics within 13 one-hour episodes: it’s a television show.

Spacey and Fincher aren’t the only Hollywood names migrating to television. Gus van Sant, director of Good Will Hunting and Milk, directed the short-lived but engrossing Boss. And who can ignore Steve Buscemi’s powerful presence at the head of Boardwalk Empire? While film talent in TV is hardly news (Pirates of the Caribbean producer Jerry Bruckheimer’s name is plastered on every CSI franchise) the big guns are moving to television on a new scale. TV has become a long-form medium for elegant storytelling.

Networks are affording huge budgets to serial shows, with Downton Abbey reportedly costing £1m an hour to film. Despite not enjoying the same funding, Australian productions in recent years have raised the bar in quality: The Slap displays raw humanity, while Cloud Street chronicles two families’ search for meaning. Television is the new immersive fiction – and it’s getting better by the year.

Jonathon Franzen sees fiction as ‘a vehicle of self-investigation…a method of engagement with the difficulties and paradoxes of my own life.’ We turn to the best shows seeking a mirror. At 15, when my homely life was bereft of Manolo Blahniks, cocktails and men in suits, my friends and I wondered which Sex and the City girl we were. And Dexter? Not many people murder bad guys methodically but we all grapple with dark, hidden selves in contrast to the polished version we display.

Brilliant television isn’t new: in the nineties, Seinfeld took acerbic aims at cultural mores. Soon after, the team behind The Sopranos combined smart writing, high production values and gritty characters with an eclectic soundtrack.

And more recently, Game of Thrones happened. The HBO adaptation of George R. R. Martin’s novels encapsulates human nature’s coupling of power and sex and takes tragedy to new extremes. The intricate themes have spun off endless essays and blog posts; several universities offer courses examining the program and book series.

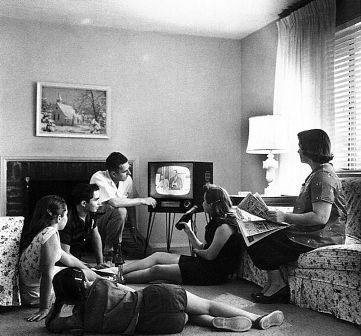

Despite evolving to greater levels of quality, TV is typically perceived as unintelligent. The late comedian Bill Hicks said: ‘Watching television is like taking black spray paint to your third eye.’

There are infomercials and celebrity shows and news programs that squash politics into three-second soundbites and shrill ad jingles and incessant messages to buy buy buy – much of the television world is empty banality.

The box can be vacuous; at worst it champions stereotypes and at best is empty of subtlety. The spiritual and the sacred are ignored by most narratives unless they can be squashed into a hasty character arc. The world’s foolishness is, at least in part, TV’s fault.

Literature has always been seen as the diametric opposite to television, in all its existential questioning and serious moral codes. Jane Eyre is about the pursuit of identity and autonomy, Slaughterhouse 5 questions free will, and Lady Chatterley’s Lover explores the depths of desire.

There’s a general perception that literature is the zenith of intelligent escape – it nourishes the intellect and links humanity through common experience. Reading classic books is a wholesome occupation: it’s good for you. In opposition, television is just an exercise in the dumbing down of culture.

We’ve all seen proof: a colleague arrives at work on Monday, groaning that she spent the weekend under a doona watching Grey’s Anatomy. Would she be ashamed if instead of the DVD series she took a Dostoevsky to bed?

The convenient dichotomy puts novels in the red corner and TV shows in the blue. One boxer is university-educated and wears glasses, which he folds up and hands to an assistant as the fight begins. In the opposite corner, the blue competitor is overweight, wears Smurf boxers from Kmart, and calls out, ‘C’arn, ya bastard!’

Maris Kreizman has no interest in the boxing ring. She pairs images from TV shows with literary quotes on her blog Slaughterhouse 90210. For more than four years, she has been coupling sentences and stills that epitomise television’s heroic struggles and metaphysical subtext.

‘Pop culture has always been the primary lens I use to make sense of the world,’ says Kreizman, who works in publishing. To gather material, she spends hours reading and watching, and searches the dungeons of Goodreads, where fanatics record quotes from favourite novels.

‘While Vonnegut influenced me as a reader and made me want to be an editor,’ she says, ‘(Beverley Hills) 90210 was really what defined my adolescence.’

Kreizman’s enthusiasm for the decade-long melodrama is typical of many teenagers from the nineties. The show captures the contradictions of adolescence: the pull of danger, the desire for escape, and the pursuit of integrity (personal integrity, writes Zadie Smith, is ‘worshipped by adolescents because principles are the only thing adolescents, unlike adults, really own’).

Television can speak directly to our experiences and aspirations – and Kreizman is honouring that with her tumblr. The linking of literature and television is a brave statement that pays tribute to well-executed TV and defies our dualistic nature of culture. Profound narrative is no longer confined to books.

The glory of a novel is undeniable: there’s a special beauty in a story’s ability to seize readers like swimmers in a riptide and wash them to new shores. When an author paints an interior life and we encounter questions of morality and fate, we examine our own lives through these lenses. But what we desire to encounter in literature (complex characterisation, vivid imagery, flawed protagonists) is increasingly common on nightly programs.

This is partly due to many television shows, like the aforementioned Cloud Street, The Slap and Game of Thrones, being adapted from books. But screenwriting alone is emerging as an art form dealing with archetypal themes and compelling plots.

While novelists can detail a protagonist losing control over his world, we observe it in Mad Men; a short story can describe a young woman’s struggle for independence, but Lena Dunhum writes it into the script of Girls. The calibre of shows like Mad Men and Girls is breaking down the dualistic conception of literature and television.

Kreizman says that one of the ideas behind Slaughterhouse 90210 is breaking the imagined divide between high and low culture.

‘Watching TV has helped me to be more creative,’ she says, ‘I think it can inspire.

‘TV can be as profound as any other form of media. And you know what? I think Bill Hicks would’ve loved Louie, I really do.’