reflections on the Human Rights Commission report into children in immigration detention

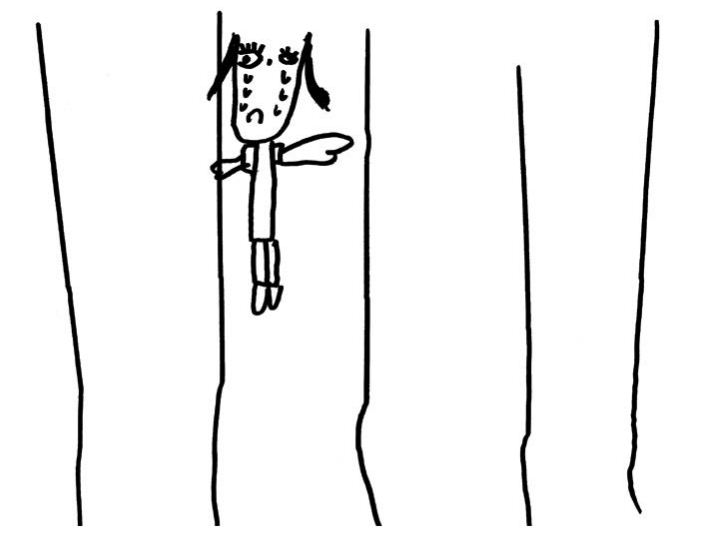

Drawing by primary school aged child, Darwin Detention Centre, 2014. (Image via Human Rights Commission, http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/4.0/)

The Australian Human Rights Commission (HRC) report, entitled The Forgotten Children: National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention (2014), was tabled in Parliament on Wednesday 11 February. The report investigates the mental, emotional, and physical ramifications of mandatory detention, particularly on children.

Reading this report, I was nothing short of horrified. The HRC’s investigation provides an insight into the despairing experiences of detainees inside Australian detention centres, including those in mainland Australia and Christmas Island, as well as providing an inquiry into centres at Nauru and Manus Island. In her speech on 12 February, Professor Gillian Triggs, the HRC President, acknowledged that the majority of the 1,138 children that were in detention at the time of the inquiry have been released. But relying on data from the Department of Immigration, Professor Triggs suggests that some 330 children remain detained.

The sobering realities of life in detention for children emphasise how inhumane Australia’s current practice of immigration detention can be, and provide an opportunity for review. I was confronted by the quotes, stories, and facts contained in the report, with the title – The Forgotten Children – serving to reiterate how overlooked these children have been. Professor Triggs noted, ‘Locking up children taints us all,’ and as an Australian, I honestly feel that I cannot escape a sense of moral complicity in being a bystander while children are incarcerated in Australian immigration, often for simply seeking asylum.

Mandatory immigration detention has been an Australian policy for 22 years, beginning in 1992: it has been in existence my entire life. It’s time for a serious government response.

Despite its severity, the HRC report sadly only sparked vitriol from Prime Minister Tony Abbott during an interview with Neil Mitchell on 3AW radio, rather than a legitimate response to the findings. Hopefully, despite the government response, the release of the HRC report generates necessary public debate, and a review of the legal and policy frameworks surrounding children in detention.

Significant HRC findings

The HRC depicts a concerning picture of life in Australian detention centres for children, citing assault and sexual assault allegations, self-harm, and mental health conditions.

Facts that I found particularly alarming include:

– 34% of children in detention, in the beginning of 2014, had severe levels of mental illness that warranted psychiatric care. This is comparable with the less than 2% of Australian children who require similar treatment.

– 30% of the adults detained with the children suffer from some form of mild to severe mental illness, which arguably creates a volatile climate for children.

– Children on Christmas Island received practically no education for a one-year period, from July 2013 until July 2014.

– 128 children self-harmed while in detention, between January 2013 and March 2014.

– On Christmas Island, the children detained occupy very restrictive living conditions; the HRC reports that the detainees reside in shipping containers that are mostly 3×2.5 metres.

– Children who arrive following 19 July 2013 are detained in Nauru for an undetermined period of time, without any specifications regarding release.

Heartbreaking responses, drawings and quotes taken from the children themselves are juxtaposed alongside these chilling statistics: mostly, the children simply recount their utter despair at being locked up for prolonged periods, and sometimes indefinitely.

As I was reading the document, I could not stop questioning, how does this happen? What are the express legal mechanisms surrounding this human rights issue?

Legal bases for detention of children

The HRC report highlights that both international and domestic law, operating in the area of human rights, clearly states that children should only be detained as a matter of “last resort”.

But:

– “Mandatory detention” is the immediate response taken against any non-citizen, including children, who do not possess a valid visa.

– As such, there appears to be a direct contradiction between the words of the Migration Act, which states that detention is to be a ‘last resort,’ and what actually occurs in practice.

If detention is deemed the only possible recourse, then, as per the Convention of the Rights of the Child, article 37(b) – to which Australia is a party – the detention must be lawful, not arbitrary, and for the shortest appropriate amount of time.

I found the “arbitrariness” that often accompanies Australian mandatory detention particularly concerning. The HRC suggests that detention is not arbitrary if it is a reasonable means of achieving some justifiable goal or aim, which cannot be achieved by alternative method. In order to assess this, the Commission stresses that individuals should be assessed separately, in order to determine whether detention is necessary for that person, and whether alternative measures may instead be taken.

Significantly, the HRC report notes that the UN has condemned the arbitrariness of Australian mandatory detention. Alternatives to detention are frequently available, as the HRC report stresses. For instance, one key option is allowing detainees to be released into the broader Australian community while immigration issues and visas are determined.

Other jurisdictions

Shockingly, Australia is the only nation in the world that has this unique approach to mandatory and possibly indefinite detention of children. The HRC points to countries such as the U.K. and Sweden, among others, which only permit to detaining children for limited periods of time, usually between 48 and 72 hours.

Other countries are able to avoid protracted periods of immigration detention for children, why can’t we?

The Abbott Government response

Ultimately, the HRC notes that the Australian government’s Department of Immigration has a duty of care to all those detained in immigration. Seemingly, there are questions surrounding whether this duty has been met.

In his 3AW radio interview, the Prime Minister chose to deflect the purported criticism of his party contained in the report, by attacking the HRC and reiterating the apparent success of his “stop the boats” policy. The reality is that the “stop the boats” policy has led to a massive amelioration of deaths by drowning, while other government action, including releases of detainees, has led to an overall reduction in the volume of children in detention. But the underlying policies surrounding immigration and mandatory detention remain, and consequently approximately 330 children are languishing in detention centres.

The human rights of children in detention extend beyond their method of arrival to Australia. By attacking the HRC for their ‘blatantly partisan’ role in the production of the report, Abbott both denigrates the credibility and independence of the Commission, and Professor Triggs herself, but also threatens to overshadow the true concerns uncovered in the document.

The HRC report offers both a significant opportunity to engender awareness of the treatment of these forgotten children, as well as an opportunity to catalyse real legal and policy change.

*Note – All references to the “HRC report” refer to the Australian Human Rights Commission’s 2014 report, The Forgotten Children: National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention (2014), unless otherwise stated.