the radical power of hysteria

I’m sitting in my room listening to Girlpool. My bed is warm and Alfie, my cat, is curled up in my arms, making my bed even warmer. I lit a candle earlier but the scent wasn’t as strong as I had hoped – everything just smells burnt.

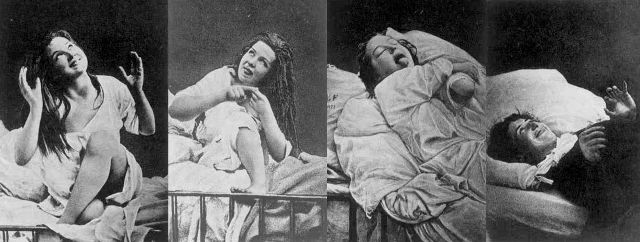

I want to talk about hysteria. It’s a word that’s used less and less nowadays but we occasionally hear about “mass hysteria” surrounding particular fads and sports teams. We know it means to be wild, irrational, loud, beyond control. But the root of the word is located somewhere very specific. Somewhere physical, even. Hysteria comes from hystera, the Greek word for uterus. And so, hysteria began its life as a Freudian diagnosis for the irrational emotionality of women. When women suffered from unexplained illness, whether physical or mental, it was chalked up to that most mysterious of body parts: the womb. They figured that the uterus could move around the body wreaking havoc. Uteruses have the unique distinction of being historical scapegoats of sorts.

Of course, this concept of hysteria is hugely sexist, but it’s also outdated. The term is, for the most part, out of use – both medically and colloquially. But it’s important to me. I think it’s the most important word in my world and I want to talk about how my relationship with this word has shaped my relationship with myself, with my body and my femininity.

In 1881, Bertha Pappenheim (better known under the pseudonym ‘Anna O.’) was sent against her will to the Inzersdorf Sanatorium for treatment for hysteria. She suffered from hallucinations, partial paralysis, anorexia, and at times, lost the ability to speak. She would go on to become the poster child for psychoanalysis, her case the most famous of all.

Bertha was highly intelligent. When she did speak, Freud – the father of psychoanalysis – said she spoke of ‘profoundly melancholy fantasies…sometimes characterised by poetic beauty’. We know the pathology of hysteria is false, so what was happening to her? As medical science improved and doctors were forced to abandon the “wandering womb” theory, since the uterus was obviously fixed in place, they decided instead that it must emit some kind of vapour. Uterine vapour was deemed the cause of most, if not all, female ailments.

I know that these ideas are dangerous and worrying. But as I read about Bertha I felt a strange connectedness to this woman whose pain refused to be easily pathologised. I knew it didn’t make sense. Hysteria has been used as a historical tool for oppression. And yet, sometimes I felt so crazy. I still do. Sometimes I feel beyond words. Despite all I knew about it, I couldn’t help but feel that behind the dismissiveness of the hysterical diagnosis, there was also a sense of fear, of mystery. Throughout history there has been a fascination with the kind of secret power that may be held in the womb. I felt that power maybe existed within me.

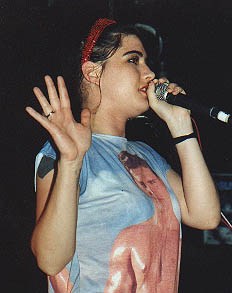

When I was 17 I went to a lecture performance called She’s Lost Control by the all-girl art collective Hissy Fit. They talked about hysteria, the made-up disease I shamefully associated myself with sometimes. But they didn’t talk much about 19th century doctors and women shut up in asylums. Instead, they talked about rock stars. They talked about the “hysterical performance” of female musicians like Kathleen Hanna. The way that she would bare her emotions: defiant and feminine and radical. For the first time, I felt the power of hysteria as something uniquely womanly; as something worth being reclaimed.

I started reading and I discovered Helene Cixous. Cixous was a French feminist philosopher who wrote extensively about the radical power of hysteria. She put forward the idea that the female experience could not be expressed through “rational” language, which is inherently masculine. Thus, the hysterical woman seeks to break free of the bounds of male rationality in order to better access herself. She implored women to “write their bodies”. Armed with the words of women like Helene Cixous, Luce Irrigay and Avital Ronnell, who described hysteria as ‘an inherently revolutionary power…’, I felt myself start to change.

I no longer feel the need to apologise for my emotions. If I’m crying, it’s not because I’m weak, but because I am not afraid to cry. I don’t see male disdain for female emotions as power, I see it as fear. I write the way I want to write. My language isn’t “flowery”; it’s true to my experience. When words fail me I experiment with the s p a c e s because sometimes that’s the truest thing we know.

I’m sitting in the library now, Girlpool echoing in my ears. I am surging with emotion as I finish writing about the word that has hurt me, taunted me, inspired me and remade me. I don’t know exactly what I’m feeling, but I relish it all the same.