lip lit: baby

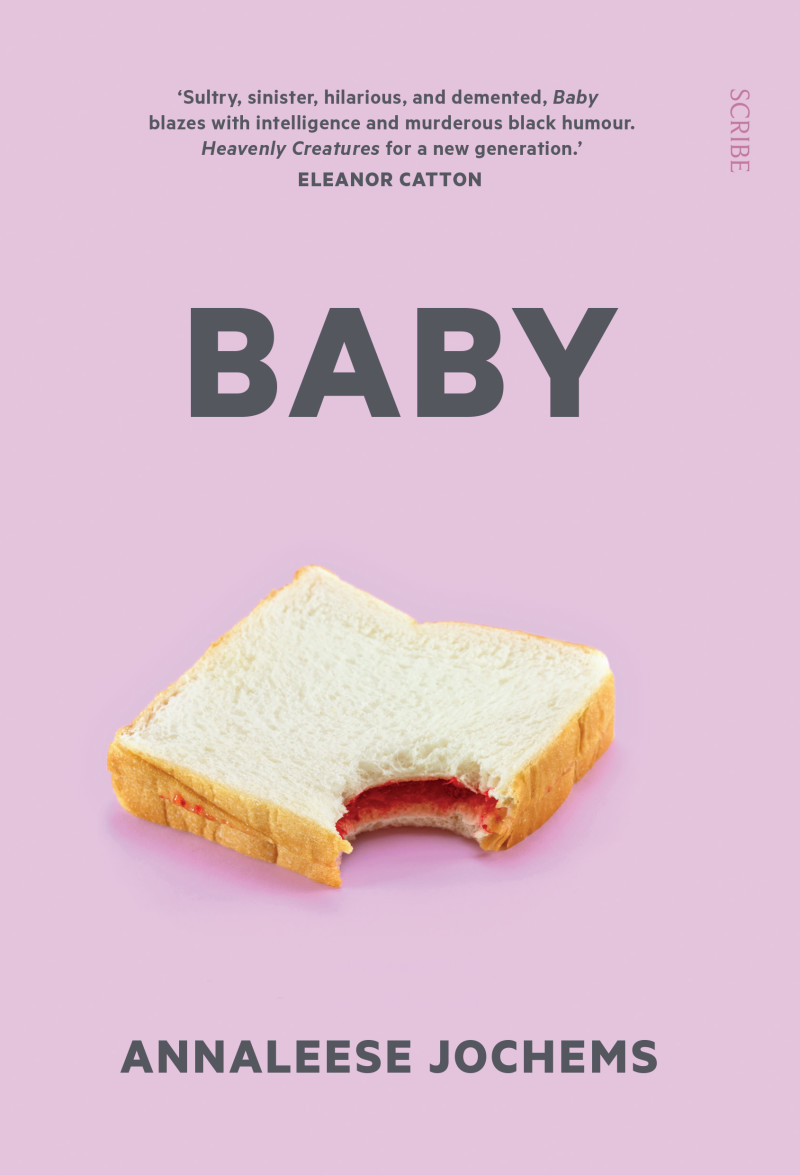

Baby by Annaleese Jochems (Scribe Publications, RRP $29.95)

“It’s got Baby written in wispy orange lettering on the side. It’s bluish-white, with dirty bits at the water line, and the sea clinging at its little hips like low-waisted pants. There are bigger boats around it, but Baby catches the sun better…

“Baby appears gradually from behind all the bigger, more robust boats, dancing like something imaginary. The water lifts her sometimes, then drops back under, exhibiting her dirty underneath.”

*

Baby is the story of spoilt 21-year-old Cynthia, who empties her father’s bank account to buy a boat and escape to the high seas with her fitness instructor, Anahera. Anahera wants to leave her loveless marriage, and Cynthia has adored her from afar and hopes to take their relationship to the next level. Baby is a psychological thriller, and 24-year-old New Zealander Annaleese Jochems’ debut novel.

After their initial escape, the book crawls along as the boat is moored in the Bay of Islands, leaving the reader unsure about where it’s heading. Time passes as it would on the boat, stuck in the monotony of canned food, swims and lazy days. The reader is left in the dark for just how long they’ve been there. In fact, Jochems references this – by page 64, Cynthia admits that she has stopped counting the days. I was lulled by this mooring, interested to learn how the narrative would progress.

Cynthia finds Toby, a 15-year-old boy who promises to give them $40 if he gets to drink beers on their boat, on land. I don’t want to give too much of the storyline away, as I think the novel is best enjoyed when you’re in the dark, but this decision changes the course of the novel, and we see a different, more calculated side to Cynthia. These actions that shift the book happen very quickly, and Jochems does not afford us the luxury of a full explanation. Instead, I found myself continuing to read to try and catch up.

Our unreliable, third-person narrator, Cynthia, gives us the sense that Anahera is an ethereal woman who is nevertheless not giving much about herself away. This vaguely threatening vibe from Anahera initially distracts us from looking too closely at the narrator herself, who seems to do little more than dream up theatrical situations and sulk.

Cynthia is almost like Muriel of Muriel’s Wedding for the new millennium. She appears to be a compulsive liar, a bit of a pathetic figure who repeatedly dramatically misreads events. She sees herself as beautiful, if “skinny-fat,” and never assumes that she won’t get her way. A character later introduced in the novel sees himself as a sociologist, making a dramatic diagnosis that Cynthia doesn’t believe in reality, “but reality TV.” Sure, it’s a stereotypical complaint from older generations towards millennials, but Cynthia’s reality indeed appears to have been warped by the vast amounts of reality television and pornography she consumes. We see how it affects the decisions she makes, as she compares what she must do to keep Anahera interested to the manipulations and exploits she watches on The Bachelor.

Cynthia does everything in the hope that people will notice. Jochems really comes into her own with this character, stretching Cynthia to absolute absurdity. At the beginning of the book, she tells Anahera that she was gifted her dog Snot-head after a bout of loneliness at 14 where she “cried every single day.” Sure, teenagers cry a lot, but this wasn’t just a regular, garden-variety cry. Cynthia would watch herself in her pocket mirror, and catch her tears in a jar.

“One day, my dad asked me what I wanted… it was our best moment of love together,” she concludes.

“He told me he’d heard my crying all that time. I felt better then, when I knew he’d been listening.”

Cynthia is deeply confused when no one at the table notices that she doesn’t like her porridge. When she’s bored, she logs onto her Facebook to read the panicked messages from her friends asking her where she’s gone and to make contact. She describes reading them as “dreamy.”

Writer Emma Marie Jones in her piece for The Lifted Brow ‘Small Acts of Planning’ posits that Jochems may just be having a little fun with Cynthia, as opposed to writing an overarching metaphor about our addiction to technology and presenting a cultivated persona online. The desire to find a message from Cynthia’s behaviour is strong here. Well, for me anyway.

The film rights to Baby have already been sold, and I look forward to seeing how the chosen director manages this constant back and forth and inner narrative that really gives Baby its own voice.

Rebecca Varcoe’s review of Baby for the Sydney Morning Herald sums it up well:

“Baby will be divisive. While fans of Otessa Moshfegh will enjoy this debut, some may struggle to stick with a character to whom they cannot possibly relate.”

And that’s where I was at. A preview reader described it as a book “not to be loved”, and I was left confused and a little disappointed. Sure, Cynthia is a gross exaggeration of the millennial but it is difficult and uncomfortable to try to comprehend her actions. Jochems makes you sit in this discomfort.

You’ll just have to row the dinghy out and climb aboard Baby for yourself.