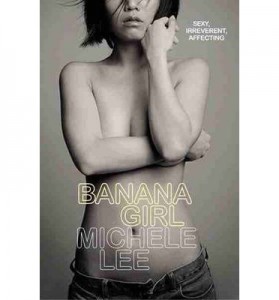

lip lit: banana girl

Playwright Michele Lee admitted in a recent interview that writing a memoir at such a young age could be interpreted as ‘self-absorbed.’ However, Banana Girl thrusts us into her twenty-somethings with such intimate realism that any self-indulgence on her part is completely excusable.

In the lead up to a four month literary residency in her parents’ native Laos, Lee becomes fixated on a letter she wrote to her adult self as a teenager, something about ‘not being a virgin’ and ‘getting a good job.’

She has no idea where the letter is now, but she’s sure her younger self would disapprove of the messy direction her life has taken.

After distancing herself from her Hmong-Australian family in Canberra, she is now firmly immersed in the Melbourne arts scene. She hates leaving the ‘hipster boroughs’ of Brunswick, Fitzroy and Northcote, and she makes her living as a playwright and part-time government bureaucrat. She lives in a sharehouse with three other women, and she is ‘ferociously’ single—meaning she trawls the internet for hook-ups with men she identifies by nickname only, like ‘The Cub’ and ‘Mercedes.’

Lee is not afraid to lay herself bare, and in doing so, she captures that feeling of being on the precipice of thirty; that magic age when we’re supposed to have everything figured out but don’t. Like most of us, she is still striving for self-acceptance.

She is frank and unapologetic about sex, a subject that dominates most of the book, though she does dwell on conversations about her lifestyle. When a housemate calls her a ‘man-eater’ she reflects that this is a ‘gentler way to say “big old slut”‘ before dismissing it as a side-effect of society’s limited vocabulary on the subject. Then she’s so preoccupied and irritated by a man she meets online that she fumes: ‘How is it even possible that I can experience giddy hope and hot rejection when I’m just a robot programmed to be on a permanent auto-fuck setting,’ suggesting she feels judged about how she is expected to behave. Her wry observations about sexual politics and being a single woman in her late twenties expose the social contradictions young women face when it comes to sex and relationships.

She also struggles with her cultural identity. Despite her distance from her Hmong family, she identifies as Hmong and the goal of her Laos residency is to get in touch with her heritage, but she considers herself the black sheep among her siblings, who are far happier to marry into the traditional Hmong-Australian culture. She feels her extended family in Laos might not recognise her at the airport, that she would ‘blend into the arrivals crowd, dismissed as some other traveller from a rich Asian country.’

It should be said that one of the book’s greatest strengths is its relationship with place, especially Lee’s descriptions of her adopted Melbourne. The city comes alive as another character in the book, where its laneways, bars, restaurants and galleries set the scene for many of her exploits. Her depiction of the Melbourne arts scene and its bohemian intellectuals is instantly recognisable, whether you’re entrenched in it yourself or familiar with it from afar.

Her writing style is also engagingly conversational, though reorienting yourself whenever she shifts to another relationship can preoccupy some of your attention. The book’s structure resembles the erratic nature of memory, darting from moment to moment to moment, and you do spend a bit of time mentally sorting her friends and lovers.

Banana Girl is something of a coming of age story for those in their late twenties. Lee is not reflecting back on her life from a great age as a traditional memoirist might, but with the immediacy and honesty of someone who is still learning about who they are. Over the course of her story, she invites us to consider our own hopes, conflicts, self-doubts and regrets, to consider how much and how little we change as we grow older, which is exactly what a good memoir should do. This is a revealing book that should resonate with anyone who has imagined defending their choices to a younger self.

Pingback: Banana Girl | Emily Tatti