lip lit interview: anna fern

What does poetry sound like? Melbourne performance poet Anna Fern is one the brightest and most exciting contemporary artists on the spoken word scene. Fern employs a full range of sonic elements in her work, from everyday objects, instruments and her voice, to create an unexpected, playful and an emotionally resonant, immersive poetic experience. I had a chat to her about how she writes, edits and performs, and her new CD Mouthful.

How do you describe you work, Anna? I feel like ‘sound poetry’ doesn’t entirely do it justice.

I’d say I’m a performance poet. I communicate with my audience primarily with words, but I’m not afraid of using the full range of my voice to show different facets of those words, and to add surprise and emotional intensity to the performance. It’s all about connecting with your audience.

How structured or choreographed is your work and its performance? Is it ever ad-libbed or free style?

I’m an editor by trade, and a bit of a control freak when it comes to my choice of words, so I’m quite uncomfortable with the idea of improvising the text of a poem. The performance of a text, the music of it, and the sonic embellishment of it, is another matter. I have pieces where there are opportunities to improvise, but it’s usually within a planned structure with a clear progression in mind. For instance, in a sound poem based on just one word or phrase, I will make a decision about the starting and finishing points and the dynamics in between. I can play with sound and repetition to exaggerate or augment the meaning of the word, with a whole array of improvised nuances, which becomes a narrative.

What is the editing process like for sound poetry?

My sound pieces usually begin on the page, and sometimes look a bit like a music score with notations on how they are to be performed. Sometimes I’ll think of an idea, but don’t know if it will work, so I’ll write it down, put it away, let it ferment for a while, then look at it later with new eyes. To edit a sound piece, I need to speak it, and assess how it feels in performance. I’m not an actor. I have to be able to feel that the words and the sound are truthful, that they work technically and aesthetically, and that I can present the piece with conviction. I know it’s working and ready to try out in public if it feels sincere and natural and I can get into a bit of an immersive zone with it. Giving a new piece a run on the open mike at a poetry venue is the real test. It forces you to see your work from the audience’s point of view and you get instant feedback. I’ll often make changes to a piece over a few outings as I get to know it better.

When I discovered the rubbing the edge of a wine glass trick as a teen I swear I did it non-stop for days. I imagine that when you were little you were the kind of kid that liked making up instruments and bashing pots and pans together. Were you always into making sounds?

I was brought up an only child in a very strict household, with the false notion that real music was written by proper composers, and played by proper musicians. I was sent along to piano lessons for a few years, but I found that whole way of being taught and doing exams so intimidating and offputting. I did like singing though—I sang in choirs at school, and was always mucking around at home harmonising with my cousins. It wasn’t really until I went to uni and moved out of home that I realised that anyone can play music on anything they want, and that it doesn’t even have to sound like music to be legitimate. That was pretty exciting.

How did you get involved with Unamunos Quroum? Who was in the group at the time?

I started going out with a glass artist, who introduced me to his arty friends who were getting into making highly resonant sound sculptures and taking them into subterranean spaces, like inside drains and bridges and underground carparks. I started vocalising with them, and met Edgar (who happened to be playing a vacuum cleaner hose like a didgeridoo and a set of pipes with a pair of thongs called a thongophone). Edgar invited me to come along and sing with Unamunos Quorum, an acapella vocal group exploring free improvisation and the whole range of the human voice. It was a loose collective, with people coming and going—I think there were about 6 people there at my first meeting—but Sjaak de Jong has always been the driving force that has kept it going for all these years. UQ is a music group, but the exploration of the voice naturally turns verbal, with made-up words, rhythmic scatting and other devices such as throat singing with harmonic overtones and percussive effects using the mouth and breath. Sound and music invoke emotion in a much more primal and arresting way than words alone. We were having intensely emotional conversations using the sounds and music of language, without using real words.

I read that you only got into performing your poetry in your thirties, maybe a little before I also got involved in spoken word (you seemed ‘established’ when I started!). What made you decide to take the leap?

I’ve always written poetry, but it takes time and practice to write well. My early efforts were earnest rubbish, and there was also the issue of stage fright to get over! I was a bit of a late bloomer, but that’s not a bad thing. As you get older and with a bit of practice, your writing improves, you have more interesting things to say, and you get more confident. The first spoken word gig I went along to was probably Passionate Tongues, in Brunswick. I performed with UQ, singing backing vocals with the poet Jeltje. Discovering this thriving grassroots poetry scene in Melbourne and seeing such a variety of spoken word being performed encouraged me to write more. The welcoming generosity of other poets was what made me take the leap from page to stage, and it was a natural progression to try come up with poetry that crossed into sound, and sound that crossed into poetry.

Your work has appeared in print, too. It’s even been inside Melbourne’s trains. That must have been a cool thing!

Moving Galleries was a fantastic opportunity for poets and artists to engage with the wider public. I got a really nice letter from one commuter saying how glad she was to read my haiku about rainbow lorikeets after having a very bad day. For me that was a really nice validation of the idea of having poetry and art on trains for everyone to enjoy.

How does gender inform your work? In the concepts behind it, or the way you understand yourself within the community?

In my youth I certainly wrote about gender politics, badly and in that earnest impassioned way young people do… these days I avoid proselytising and my writing is all the better for it. It still shocks me when poetry venues feature lots of older male poets and lots of young female poets, but overlook older women poets who have a lot more really interesting things to say. How come they get so few paid features compared to their older male counterparts? Apart from anything else, it’s really bad showbiz and makes for a dull evening’s entertainment to not have older women’s voices in the mix!

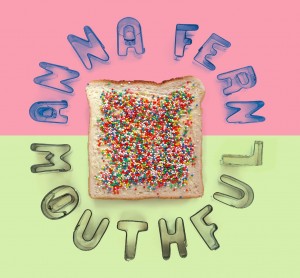

Congratulations on the new poetry CD Mouthful. Why fairy bread? (I mean, I LOVE fairy bread.) And what can we expect from this collection?

The CD is a mixture of my favourite poetry pop hits. They are tales from ordinary life, direct, truthful and sometimes really out there! Fairy bread is so simple and ordinary, but it’s also beautiful and playful.

Anna Fern’s Mouthful can be purchased at Collected Works in Melbourne and Red Wheelbarrow Books in Brunswick.

When I discovered the rubbing the edge of a wine glass trick as a teen I swear I did it non-stop for days.

Ha, I was the sort of kid who caused an absolute ruckus. We had these great coloured aluminum cups, see, that gave out a tone when you flicked them, and I experimented putting different levels of water in them and arranging them by tone so you could make sounds on them.