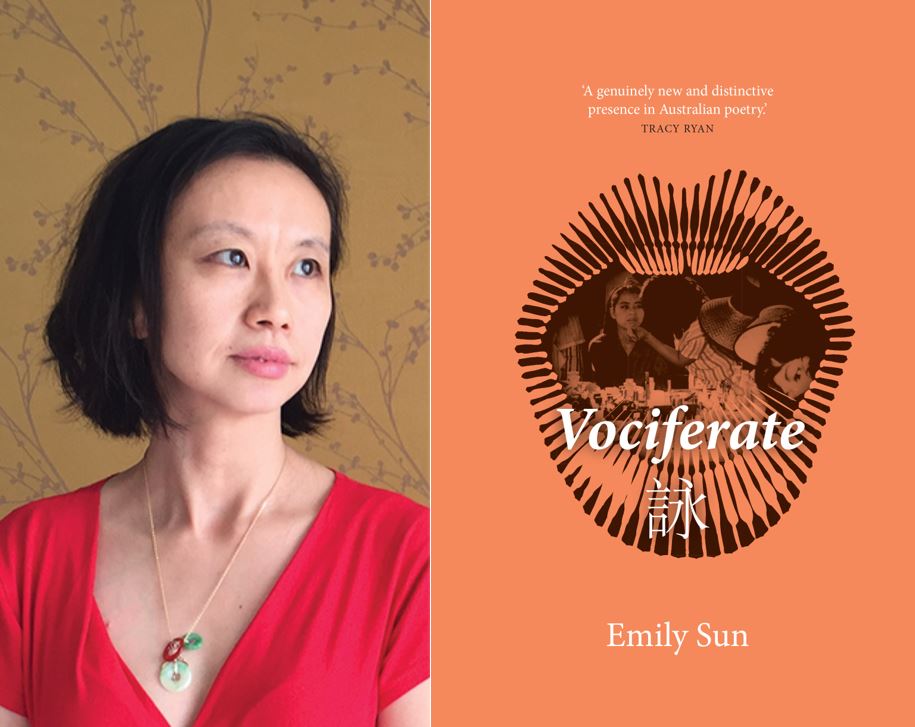

lip lit: Q&A with author Emily Sun about her debut collection of poetry ‘Vociferate’

(Author Emily Sun)

Vociferate (Fremantle Press, June 2021, RRP: $29.99)

Vociferate is West Australian writer Emily Sun’s debut poetry collection. In it, Emily meditates upon a range of issues that have shaped her world. Emily was born in British colonial Hong Kong to stateless diasporic-Chinese parents, who are descendants of Chinese sojourners to South-East Asian countries. Emily moved to England at age three before immigrating to Perth with her family.

We spoke to Emily about how her collection examines issues of belonging, cultural heritage, individual and national identities, the legacy of colonial rule, as well as more personal subjects such as intimate and social relationships.

*

Congratulations on your collection. How do you feel since its publication? What was the process from writing to publication like for you?

Thank you! It is my first book, so I was elated when Fremantle Press called me on Christmas Eve 2019 to let me know it was accepted for publication. It’s been a year and a half since then (the publication was delayed because of COVID-19) but I’m still very excited! It has taken three or four decades to collect the experiences that have enabled me to write the poems, but I wrote most of the poems in 2019. I really loved the process of drafting and editing the poems and working with my editors. I have to admit that as an introvert (albeit one on the extroverted end of the spectrum) I am a little nervous about having to share these poems in person with the wider world. Having said that, one of the reasons I write poetry is because I am asking, ‘Hey, has anyone else felt this way too?’

Alice Pung has described your book as ‘polemical, personal and political’. How would you describe it?

I would say it is a book about the things that have shaped my world. The world is political, the political is personal. It is polemical because how can it not be when it is about the things that have shaped my world.

You’ve said this book is an expression of ‘minor feelings’, a term popularised by American writer Cathy Park Hong to describe the ineffable emotions experienced by minority groups. Can you tell us more about that?

Hong wrote a whole book about it, and I find it difficult to summarise these feelings in a short answer – which is why I write poetry and prose. Hong writes about the Asian-American experience and the dissonance between American optimism and the racialised reality. That too exists here in Australia. When we express something that doesn’t fit into the grateful/happy/model migrant or refugee trope, it’s seen as ungrateful or overly aggressive. I remember at school, some teachers would refer to me as ‘bolshie’, ‘surly’ and ‘aggressive’ because I wasn’t a model minority. I wasn’t a straight-A student. I wasn’t always smiling and respectful, but I wasn’t causing a riot in the classroom, and I was probably on average an A-minus student. I remember getting a B-plus once in a subject I usually excelled in, and one of my teachers made me feel as if I’d completely failed. I had my suspicions about some teachers confirmed when I became one myself and got to see things from the other side.

I don’t feel comfortable speaking about my more recent experiences. All I can say is that I still have had to work hard on not making myself small and minimising my achievements.

Did you set out to write a feminist book?

Yes and no. Until now, poetry has always been something I’ve written for myself. It’s only now that I’m older that I am more confident about voicing what I’ve always felt, but I didn’t set out to write a poetry collection. When I made the decision to collate and submit my poems to a publisher, I saw that many of my poems expressed these ‘minor feelings’ and how, in order to move on and write anything else, I needed to declare my position.

Do you think the complexity of your identity plays a role in your relationship to feminism? What is feminism to you? Has it evolved over time?

As a child, I thought of feminism as having equal rights to my male counterparts.

I grew up with very mixed messages about what being female meant. Although both my grandmothers were essentially single mothers and independent women, my mother was raised in a very feudal environment. She had her education cut short because she was a girl, and my grandmother believed that no man would appreciate an over-educated woman. I’ve always wondered what sort of person my mother would have been had she not grown up in such a traditional household and married so young.

I grew up with an awareness of the limitations imposed upon me because of my sex and gender. As progressive as my father was for a man of his generation, I remember him telling me about how if I’d been born a boy, he would have taken me camping. My grandmother and mother always commented upon what a pity it was that I was a girl because my personality was more suited to that of a boy.

I couldn’t really identify with earlier waves of feminism because it was so white and middle class. It’s only when intersectionality was introduced by third-wavers that I connected to some aspects of mainstream feminism.

There is still not only a glass, but a harder ‘bamboo-ceiling’ to break through. I was acutely aware of this when I attended a conference a couple of years ago and saw that in China, there were women younger than me who ran literature departments at their universities. I can’t really see that happening here in my generation but maybe I will be proved wrong.

A number of poems deal with cultural stereotypes, but it’s not a one-way street in poems like ‘Double Exotic’. Was it difficult to tread that fine line between challenging and reinforcing stereotypes? How did you manage it?

‘Double Exotic’ was a playful poem that I wrote for my partner when I realised that I hadn’t mentioned him at all! He is Italian-Australian, and when he was younger was subject to people fetishising his race and gender. I suppose it’s really up to the reader to decide whether or not I was successful in treading that fine line, and a lot of that depends upon where they are positioned as readers.

Did your family and your family’s heritage come out in the collection? If so, how?

As I mentioned earlier, once I decided to arrange the poems chronologically, the project became a more personal one. I explored my own identity and sense of belonging in many of the poems as someone with an imposed and self-ascribed ‘Asian-Australian’ identity – or if you want to be even more specific ‘Chinese-Australian’, and diasporic-Chinese identity – so of course it comes through, especially in the first two sections of the book. In the final section, I address the other identities I’ve accumulated over the decades, such as: worker, partner, cancer survivor, and carer.

Many of our readers are young women. If you had to pick one or two poems from your own collection to read to your younger self, what would they be and why?

I think my younger self would have been happy to have read anything that reflected some of my own experiences. In terms of poetry, I grew up on a diet of English literature because that was all I had access to back then. The ones that spoke to me were Shelley’s political poems such as “England in 1819” and the “Masque of Anarchy”, and the first world war poets such as Wilfred Owen. It’s hard for me to know which of my own poems I would have enjoyed if I had access to my book in my teens. I know that if I had access to Asian-American poet Marilyn Chin’s work as a teen, she would have been my favourite poet.

I suppose at that identity formation stage of my psychosocial development i.e. in my later teens, I would have enjoyed reading the poems that made me feel that it was okay to express anger and frustration at how I was being treated as a young woman, and more specifically as a young Asian-Australian woman.

The collection is multi-lingual. Which languages do you write in and why?

I’ve adopted the ‘translanguaging’ approach, which is using all my linguistic capabilities to communicate. I write mainly in English because it’s the only language I can write in without the use of translation apps. I also write in Chinese because I am bilingual; my mother tongue is Cantonese, but I’m only able to write in Chinese because I had some formal lessons in Mandarin. My partner told me that recently that I sleep talk in both English and Cantonese.

I’ve made the distinction between Cantonese and Mandarin because I didn’t understand or speak Mandarin until I took formal lessons as an adult, so it sits in the same part of my brain as French, which I also learnt in a classroom. The other languages are bits I’ve picked up here and there.

You worked with distinguished and award-winning poet Tracy Ryan as your editor. She calls you a ‘genuinely new and distinctive presence in Australian poetry’. What was working with Tracy like? How did she help shape the final work?

One of the best things about getting a contract with Fremantle Press was that I got to work with Tracy. Before I worked with Tracy, the only other person who’d given me significant feedback on my poetry was Nadia Rhook. If I hadn’t met Nadia, I’d still be writing poetry for an audience of one!

Tracy read my original submission and suggested that I take out one or two poems that didn’t quite fit the theme, and she pointed to things that needed to be ‘amplified’ for readers. It was also the first time I’d spoken at length to someone about what I was trying to do with the collection as a whole. I really enjoyed the editing process with both Tracy and my publisher, Georgia Richter.

Did you do research for the book? If so, what did you discover?

I didn’t have to do that much extra research for the book in terms of references to historical and global events, but I spent a significant amount of time trying to figure out how to write the Cantonese words. Neither of my parents are native Cantonese speakers. I picked up most of my Cantonese from my maternal grandmother who spoke what is best described as mid-twentieth-century Hong Kong vernacular, which was a mix of old school Cantonese and late twentieth-century Hong Kong slang. I also picked up some South-East Asian (Malaysian/Singaporean) Cantonese that Hong Kong people do not use from friends. I don’t really understand idiomatic Chinese because so much of it is tied to a culture that is so foreign to me, even though it is my heritage culture.

Does the idea of a blank page excite or terrify you?

It depends. When it’s a blank word document, it terrifies me because it means it’s time to formalise my work, but a blank piece of paper excites me. I draft ideas on paper with ink.

Let’s talk books. What have you read recently and what’s on your TBR pile?

I recently started my PhD so my reading list has been dominated by academic journal articles. However, I developed a project where I do get to read a mix of non-fiction, fiction and poetry. The most recent books I’ve read include Australianama by Samia Khatun, which maps out the history of South Asian immigration to Australia; Billy Sing by Ouyang Yu, which is a fictional autobiography; Mirandi Riwoe’s novel Stone Sky Gold Mountain; and Natalie Harkin’s Archival-Poetics. From that brief list, you can probably figure out what my current project is about.

I also recently read Poems That Do Not Sleep by my fellow Fremantle Press poet Hassan Al Nawwab, and the next two poetry collections on my ‘to buy’ list are Carlina Duan’s Alien Miss and Evelyn Araluen’s Dropbear. If I had unlimited time and funds, I’d probably buy everything on Cordite Poetry Review’s list of forthcoming collections. I usually read more broadly, but I’ve had to be quite selective recently because of my PhD.

Have any books or writers had a significant impact on your life or your writing?

As a child, I looked to Anne from Anne of Green Gables as a role model because she was someone around my age who was also aspiring writer! It didn’t matter to me that she was fictitious, nor that she lived on Prince Edward Island in the Victorian era. I was disappointed when I read the latter books and saw that she gave up writing when she married Gilbert and deferred to her student (a young man), and said that he was the real writer.

There’s also Randolph Stow’s Merry-Go-Round in the Sea, which I read in high school. The book inspired me to leave Perth, and when I read his biography, I understood why it spoke to me more than any other book I read in my teenage years.

There is of course is Amy Tan, who I didn’t discover until after I left school. There are some writers who distance themselves from Tan’s work as they don’t want to be pigeonholed as ‘ethnic writers’ but without her, I wouldn’t have known that I could write and publish fiction about my heritage in English. Tan’s work was for me the gateway to a whole new world of Asian-American literature and Asian-American studies. There is also of course the poet Marilyn Chin.

I started dabbling in creative writing as an adult, after reading Joyce Carol Oates’ short story collections. I especially loved her experimental works, and she showed me it was perfectly acceptable to return to themes already explored in previous works. When I worked in admin, I used to type out JCO’s short stories, instead of doing whatever it was that I was supposed to be doing, after I read that it was how some writers developed their voice. Michael Ondaatje’s The Collected Works of Billy the Kid is also a significant book in my life, and I could also include the film maker David Lynch. I’m heavily influenced by his work and practice in both my poetry and prose.

There are others, but these are the ones I immediately thought of so I will leave it at that.

What does literary success look like you to?

I’ve never really thought about this. I think that if I write one thing, even if it’s just one poem or one short story, that a stranger connects with then I’ve achieved more than I’ve ever dream of. Everything else is just a bonus.

*

**GIVEAWAY** Thanks to our friends at Fremantle Press, we have one copy of Emily Sun’s Vociferate to give away to Australian readers. Simply email [email protected] with the subject line ‘Vociferate’ by 5pm Thursday 26th June, 2021 for your chance to win. The winner will be chosen at random. Good luck!

I would love to read Ms Sun’s book and to experience her journey from the perspective of a Chinese- Australian. I am currently preparing professional learning for Department of Education teachers on the curriculum priority , ‘Asia and Australia’s engagement with Asia. I believe poetry from a Chinese-Australian person who grew up in Perth would resonate with teachers. Also it would be a great way for teachers to explore , with their students, the marginalisation of many Asian migrants and to build increased empathy, respect and understanding towards these groups.

This is a great interview. I am a lit teacher and have been looking for something like this! My department has been teaching Mao’s Last Dancer and Balzac and the Little Seamstress for over a decade.