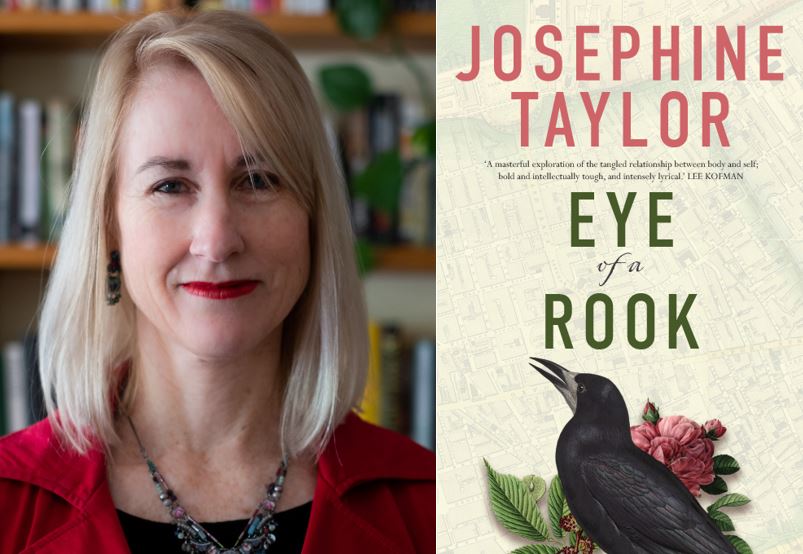

lip lit: Q&A with author Josephine Taylor about her debut novel Eye of a Rook

Author Josephine Taylor (‘Eye of a Rook’, Fremantle Press, February 2021, RRP: $32.99)

Josephine Taylor’s new work of historical fiction brings into focus a hidden condition called vulvodynia. It’s a chronic pain experienced by too many women, many of whom are under 25. We spoke to Jo about the book, the condition and her research into the history of hysteria, female sexuality, and the treatment of the female body for Eye of a Rook.

*

Congratulations on your debut novel, Eye of a Rook. How do you feel since its publication? What was the process from writing to publication like for you?

Thank you! I feel enormously grateful to see my novel out in the world.

I began writing Eye of a Rook at the start of 2013 and finished in August 2018. That sounds like forever, I know, but I could only work on the manuscript in snatches of time, as I was busy lecturing at Edith Cowan University and then working at the literary journal Westerly, where I’m an Associate Editor. It took a year until the [manuscript] was accepted for publication; I had only a handful of rejections, but I needed to recover between each one! Then it was on to editing, which I love. The novel was slated for release in November 2020, but obvious world events delayed publication until February 2021. As it turns out, though, this was perfect timing, as my Rook came out after the release of some wonderful non-fiction titles focused on women’s pain and disorder.

Many of our readers are young women. Can you tell us what vulvodynia is and its effects on younger women?

Vulvodynia is unexplained vulvar pain or discomfort lasting three months or longer. Symptoms can be localised and provoked (e.g. pain at the entrance to the vagina with tampon insertion or intercourse) through to generalised and spontaneous (e.g. constant widespread pain over the genitals). Some women have always had the discomfort, whereas for others, the symptoms have developed later in life (e.g. after surgery or chronic infection). There is no one cause and no one treatment for all, though pelvic floor re-training helps many. Prevalence in reproductive-aged women is somewhere between 10% and 28%.

Unfortunately, the highest incidence of symptom onset is between 18 and 25. As this is a time when a woman is exploring her sexuality and often wanting to connect with a long-term partner, vulvodynia can be doubly distressing. While it is not a sexual condition but a pain condition that can impact sexual expression, sex is often where the emotional pain develops too. When do you tell a person you’re becoming intimate with that you have pain with penetration? How do you tell them where it’s okay to go and where not? If they are confused or uncommunicative, how do you deal with their response? Repeated pain with intimacy and the difficult feelings around all this can feed into protective muscle guarding, which only compounds the problem. It feels bloody unfair that a young woman has to deal with all this when she is only just learning how to articulate what she needs and wants in a relationship, and I feel for the young people in that space.

I should note, too, that I’m a heterosexual cis-gender woman, so I have a vulva and a male partner, but genital pain isn’t dictated to by biology or gender and can be experienced by anyone, with anyone, and in any part of the genitals, no matter the form they take.

The book came about after your own experience of chronic pain derailed your career as a psychotherapist. Tell us how your lived experienced helped you become a writer.

I developed vulvodynia in 2000, though it took many months for me to receive any kind of diagnosis. My symptoms were at the extreme end of the spectrum, and when I couldn’t recover, couldn’t work out why the pain was so severe and couldn’t do anything else productive, I began writing. That was in 2003, when medical articles were few and often misleading and when the internet offered very little information, let alone support. So I developed my own, starting a support group, appearing in the Woman’s Day, and also researching the history of genital pain and hysteria, just as Alice does in my novel.

Eventually, I undertook a PhD, writing an investigative memoir focused on vulvodynia. It wasn’t until 2013, though, just a year or so after I’d finished this, that I began to write fiction. What was unexpected and wonderful was the freedom and joy that writing my novel gave me. As well, my experience of pain was changed through working creatively.

Your novel has been described as ‘a compelling, intelligent, lyrical and distinctly feminist narrative’. Did you set out to write a feminist book?

I feel like an accidental feminist in some ways, because it is vulvodynia that made me begin to question the way in which female disorder is seen. In some ways, it was my research that turned me into a feminist, even though I’m not completely comfortable with the label ‘feminist’ – because I like to push against labels and categories, I think!

What is feminism to you? Has it evolved over time?

‘Anger’ is the first word that comes to mind as I read these questions.

Anger has bad press, but it was anger at the gap between the (high) incidence of vulvodynia and the (low) knowledge and awareness around it that needled me into writing; anger at the unnecessary suffering this gap causes and anger at what I learned as I researched and wrote that kept me at the desk. So, I’m a fan of well-directed anger these days.

There are reasons women are angry, including the weight of patriarchal history and the stubbornness of gendered inequity. I would have hoped we’d find more genuine equity in pay, work conditions and behaviour towards women since the second wave of feminism, but recent events have shown us how deeply embedded disrespect for women is in the infrastructure of society, including (especially?) in politics. Women are angry for legitimate reasons, and feminism is critical in stoking that fire and directing it into channels that make a difference for all.

Tell us about what research you did for the book and what you discovered.

I began researching vulvodynia in 2003, and that led into researching the history of genital pain and hysteria in my PhD, Vulvodynia and Autoethnography. My findings enter Eye of a Rook through the research Alice Tennant undertakes to make sense of her inexplicable disorder. They also inform the narrative of Emily Rochdale in 1860s London, and the challenges she and her husband, Arthur, encounter as they try to find an effective treatment for her debilitating pain. I also researched Victorian England in depth, focusing especially on daily life, politics, Rugby School and London. This was essential in creating a convincing sensory impression of Victorian England in Arthur’s narrative and Emily’s letters.

What I discovered, and what Alice discovers, through research in medical history, is that female genital pain has been recorded since antiquity. It was even described accurately and sympathetically in the nineteenth century, before psychoanalysis effectively hijacked female sexuality, and society and medicine skipped down the path of, if you can’t fix it, the problem must lie with the patient and her unconscious defences (it’s ‘all in the head’). Other discoveries? The history of hysteria has always been about women, but (mis)understanding and treatment have been driven by men, their sexuality and anatomy the superior norm. Victorian-era surgeon Isaac Baker Brown performed his radical operation for hysteria and related conditions on countless women, right in the heart of London. This last discovery prompted me to bring Brown into Emily’s story, to see what choices she might have when it came to surgery, and to find out if Arthur is able to love her in the way she needs, when it counts the most.

Eye of a Rook takes place in two different settings and times. Did you write those in parallel or as separate narratives?

I tended to work on one timeline at a time, going back and forth as I finished a major section. Once I began to experiment with interweaving the three threads – Alice’s narrative, Arthur’s narrative and Emily’s epistolary perspective – more vignettes formed themselves, and I found a real magic in how they began to inter-relate. Those who have read the novel will know what I mean!

I’m interested to know what your book is saying about the relationship between our bodies and our sense of self.

I think we spend a lot of time trying to get away from our bodies. We’re obsessed with them, sure, but only to the extent we can make them do and look like what we want. Otherwise, we tend to forget we are, fundamentally, animals.

When something goes radically wrong in your body, though, you have to re-evaluate your relationship with it. Both Alice and Emily find their sense of self devastated by vulvodynia, and they both grapple with who they are as women and sexual partners, feeling at times utterly useless. When your life is upended that completely you often just want to return to who you were; I fought vulvodynia for many years and Alice does the same initially. When fighting gets us nowhere, though, we’re forced to find another way. There is a lot to be gained by learning about the kind of body that is formed by sensation and forged through pain – it’s so different to the symmetrical beautiful image we strive for but it has its own deep wisdom, as Alice learns. Ultimately, our bodies, minds, brains, hearts are not separate entities, but expressions of one irreducible self, and that’s a creative space to enter.

How does the physical experience of pain play out in the intimate relationships between the characters?

Alice and Emily both have full and satisfying sexual lives with their husbands before the onset of vulvodynia. In this, I was combating the myth that the woman with vulvodynia is somehow frigid and that this is what caused her condition. I was also really interested in how partners – men, in this case – respond, which is one reason Arthur’s is the primary perspective in the historical narrative.

We tend to think of Victorian men as rigid and controlling, and modern men as more emotionally insightful, so it was fun to flip the stereotype. Duncan and Arthur respond in contrasting ways to their wives’ prolonged suffering, with Duncan increasingly threatened by the stronger, more certain woman Alice is becoming through her research and writing, and Arthur continuing to try to help Emily, even though she has withdrawn from him, emotionally and physically. I enjoyed suspending the uncertainty around the fates of each relationship, because that’s what it’s like in real life: we don’t know the outcome ahead of time.

Your book covers some intense themes but it is full of hope – mainly, I think, because of the way your characters develop a sense of their own power by the end of the book. Is empowerment the key to happiness or acceptance or both?

I’m so glad to hear this! Though pain is very obvious in both narratives, hope and possibility are central to the novel and to what I wanted to achieve in the writing. We all struggle at some points with what life gives us to bear; what’s important is the relationship we form with that suffering. While it’s natural to be made helpless by the impact of vulvodynia, it’s disempowering to be the victim of pain over the long haul. As I wrote Eye of a Rook, I found myself empowered by the creative process, by listening to what the story demanded of me. Being an equal partner to pain means that you are no longer being defined by it; instead, you are now defining who you are and what you are becoming. Empowerment definitely brings acceptance, and I’m not sure that we can have lasting happiness without accepting who we are.

Does the idea of a blank page excite or terrify you?

Oh, excite, absolutely! A blank page is like an opportunity. It gives me a sense of liberation, knowing I can trust what comes to me to fill it, and that will be the exact right thing for that moment in time and that space.

Do you find your experience as an editor helps or hinders your writing practice?

Helps. I know that writers are often advised to separate out the writing and editing processes, but I edit as I write. I’m a confidence writer: I have to shape a scene till I feel it works before I can move onto the next one. That doesn’t mean the scene won’t be scrapped or radically changed later, of course!

Let’s talk books. What have you read recently and what’s on your TBR pile?

I read The Imitator, by Rebecca Starford, recently, and I’m currently reading The Breaking, by Irma Gold. Next up is the novella Born Sleeping, by Australian writer H. C. Gildfind, which won the Miami University Novella Prize in 2020. Where the Line Breaks, by debut author Michael Burrows, beckons just beyond. I’m passionate about Australian fiction and try to keep up with new releases.

In non-fiction, I had a reading splurge of books relating to female pain and disorder just ahead of the release of my Rook, and I can recommend all of these: Unlike the Heart, by Nicola Redhouse; Show Me Where it Hurts, by Kylie Maslen; Pain and Prejudice, by Gabrielle Jackson; and Hysteria, by Katerina Bryant.

Have any books or writers had a significant impact on your life or your writing?

Oh, so many!

Earlier in life, Alice Through the Looking Glass, Mary Poppins Comes Back, A Wrinkle in Time and The Lord of the Rings were favourites. My big thing was escaping into another world, and the worlds in these books were so beautifully realised that it was sometimes hard to come back to my own!

I respect Australian writer Robert Lukins’ commitment to the craft and pursuit of excellence. His novel Everlasting Sunday remains my favourite debut; it is appalling yet beautiful, ethically complex and impeccably restrained. Tegan Bennett Daylight’s work is always interesting – as you can imagine, I love her essay ‘Vagina’! In Perth, I admire immensely the work of Joan London, Susan Midalia and Amanda Curtin, among others.

What does literary success look like you to?

Something that lasts. I’m immensely grateful for the success of my debut, and I hope that success spreads, but I’m also interested in finding acknowledgement over many years. This is dependent on the other part of what I consider literary success: always growing my craft as a writer. I see being an author as an apprenticeship in writing that never ends, so success to me is about remaining open to what I can learn as a writer.

*

**GIVEAWAY** Thanks to our friends at Fremantle Press, we have one copy of Josephine Taylor’s Eye of a Rook to give away to Australian readers. Simply email [email protected] with the subject line ‘Eye of a Rook’ by 5pm Thursday 26th May, 2021 for your chance to win. The winner will be chosen at random. Good luck!