exploring the grotesque with artist mimi leung

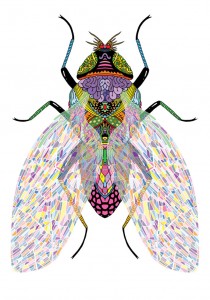

Artist (painter, illustrator and printmaker) Mimi Leung has a fascinating ability to make the grotesque adorable. Depending on whether the work is commissioned or Leung’s own, it exists somewhere on a spectrum of cartoony to psychedelic, but is always brightly coloured. When I attended the recent opening of her current “Australian Roadkill” show at Lamington Drive in Melbourne, my fellow viewers and I were “ooooh”ing and “eeeew”ing in equal measure. The walls of the small space are covered in Leung’s newest paintings; paintings of some of Australia’s most treasured roadkill. The theme is undoubtedly macabre, but Leung’s zany depictions allow the mangled creatures to retain their cuteness. I asked Leung what prompted her to paint a collection of dead animals:

“I moved to the country over Christmas and started noticing all the dead animals on the rural roads and along the highway. I was surprised and shocked by the number, variety and size of them. You rarely see big roadkill in the UK, so to see kangaroos and wombats made me look twice. Also really beautiful birds and little bunnies. Why don’t we care more about that? It seemed so callous and cruel, to leave behind us these ruined bodies in the wake of our commuting. It’s like we’re so desperate to get somewhere that we don’t care what the costs are. According to some statistics, in 2012 alone close to 16, 000 wallabies were killed on Australian roads, as well as over 108, 000 possums. I find this a bit disturbing… yet I drive on.”

Leung says her work doesn’t aim to pose political questions or convey political opinions, although she concedes that others may view it that way.

“Usually, when I try to make political or activist work, it ends very dull and predictable or patronising. I can only respond to things in a way that feels right to me and hope that others can connect with it on some level. I work best when I start from a point of not knowing, which allows me to be a bit more playful. I don’t like having a grand idea and purpose to start with, this has always lead to fairly uninspiring results for me in the past. I can only present things and provide some information for others to contextualise them in a certain way, but people read what they want into a piece of work and sometimes work that I feel is political/activist may fall way off the mark for others.”

Looking at a chronological list of group and solo shows has left me scratching my head; Leung has been zig zagging between Hong Kong, England and Australia since her first show in 2005. She tried living in Hong Kong, but the life-style didn’t suit. She now lives in regional Victoria. I asked her how, if at all, her multi-national career impacts her work:

“With my own work, of course I am influenced by the things around me and what’s going on with where I’m living. I’m very impressionable and it takes me a while to figure out what my voice is amongst all the noise from my surroundings.”

Regarding living in Hong Kong, Leung tells me

“I felt so crushed and there seemed to be no place for my own freedom, without having to live by external pressures and rules. So I created my own world, which I saw as a reflection of the ugliness around me and the way it made me feel. I hated everything but I dressed it up in bright colours and cute things because that’s what people wanted, that seemed to be the only thing people liked and accepted. I couldn’t just make ugly work, I had to make ugly work that people liked – otherwise who would give a shit? It was really quite cynical, but it ended up finding an audience.”

Much of Leung’s personal work incorporates potentially troubling imagery, including blood, guts, a man losing his skin and many frowning faces. I asked her if she thought her work was gendered, and she brilliantly responded that “most people have access to colour, why should it belong to anyone in particular?” Leung eschews the idea that the puke in her work is “girly puke” just because it’s cute. I can’t help but mention, however, that as little girls – and even as adult women to some extent – we’re told that anything disgusting isn’t feminine. We’re sugar spice and everything nice to little boys’ snips and snails and puppy dog tails. Leung rejects the notion that these ideas necessarily permeate the arts world; they certainly don’t in her case.

“Women are probably more familiar with gross things than guys, I mean gross bodily things – periods, sickness, childbirth. But I think everyone is the same kind of gross when they throw up, aren’t they? Same as how everyone is the same kind of gross when their guts fall out, or when they sweat loads or get the shits. That’s kind of my point. We look for differences, but I want to treat everything the same. Death, decay, pain and suffering makes everything the same – even animals.

I use colours so people are more likely to like the work and not turn away from it disgusted. I don’t want it to be about the horror of these things, though some people might see it that way, I want to accept them as the daily part of life that they are. Why shouldn’t we hang lovely pictures of blood and guts up on our walls just like we do flowers and sunset landscapes?”

I hated asking Leung about her thoughts on gender and race in her work and in the larger arts world. These are not questions that white male artists are expected to answer, and Leung’s art is beautiful and outrageous without any biographical context. But with a client list including Nike, AOL, The Guardian and The New York Times, Leung has a unique lens into what makes an artist commercially successful.

“My experiences of ‘successful artists’ is dominated by white males who dedicate a substantial chunk of time, energy and brain power to maintaining their position and image within fine arts, often more than what they would spend thinking about the meaning and motivation behind their work. It’s sometimes so much about their own ego and perpetuating their sense of personal fulfilment… why should I be a part of that? Their work isn’t relevant to me.”

Leung posed a question back at me:

“Does a person’s art have to be defined by their gender, race or sex or whatever other part of their identity…? And how much can the artist control how others view their work?”

White male artists who are commercially successful aren’t asked identity questions because their identities don’t deviate from the “norm” of what we expect of an artist, although hopefully that will continue to shift. And art does not exist independently of the artist. For example, Leung’s experience of living in Hong Kong, England and Australia no doubt shapes her worldview and as a result, her art. But as she astutely pointed out, whether her experience does or does not shape anything about her work doesn’t change the fact that I’ve already made that assumption. I have gendered her work, not her.

The bizarre and adorable fantasy world of Leung’s work is a welcoming and approachable one. It has a Suess-like quality and like Leung herself, it is delightfully cheeky and thought-provoking.

Watch this space, you won’t want to miss anything Mimi Leung.

Mimi Leung’s “Australian Roadkill” is at Lamington Drive in Melbourne until August 2nd.