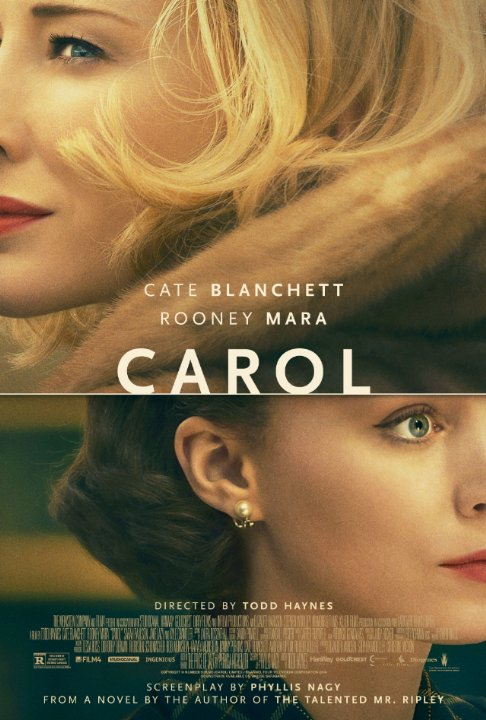

film review: carol

It’s difficult to think of a recent film more exquisite and more perfect than Carol. It may seem too soon to call the film a masterpiece, but I can confidently say that it is truly up there with some of the greatest movies of recent times. More importantly, it takes its place alongside Brokeback Mountain as one the best films of LGBTI cinema. Director Todd Haynes has made a career of making movies that are edgy and far from conventional, with his last film I’m Not There giving us multiple impressions of Bob Dylan through the performances of several different actors. Before that he was making films like Velvet Goldmine and Far From Heaven that helped bring queer cinema into the mainstream conversation.

From the moment Carol starts we’re flung into a world of Christmas in 1952 New York, with the most beautiful production and costume designs imaginable. Carol Aird (Cate Blanchett) is a wealthy housewife whose marriage to Harge (Kyle Chandler) is constantly being tested. Therese Belivet (Rooney Mara) is an aspiring photographer working in a department store with an eager boyfriend, Richard (Jake Lacy). One day their paths cross and they fall in love at first sight. Each woman struggles to understand the feelings she has for the other and face adversity from opposing forces that want to keep them a part.

Based on the 1952 novel The Price of Salt by Patricia Highsmith (who originally published it under the pseudonym Claire Morgan), the film’s narrative goes beyond its initial origin as a pulpy lesbian paperback by transforming into an artistic piece of cinematic mastery (although it must be stressed that the film doesn’t completely dismiss its radical pulp fiction roots). The film can be seen as both a queer coming of age film and a queer mid-life crisis film, with both our protagonists struggling to define the love they feel for one another. In the second half of the film, the pair embark on a journey of self-discovery through their fascination for one another.

Both Mara and Blanchett give breathtakingly beautiful performances as two women in very different stages in life who are both going through the same situation. Todd Haynes’ direction is perfect and careful. There is not a single frame in the film that looks out of place or is off balance. Screenwriter Phyllis Nagy initially wrote the first draft of the screenplay in 1996; after 20 years of love and attention, her hard work to condense the novel and turn it into a milestone of queer cinema has truly paid off. Cinematographer Edward Lachman lavishes us with close-ups, leaving us staring open-mouthed at the impossibly beautiful faces of our two leading women as subtle emotions flitter across their faces. The perfect production design transports us to 1950s New York in a blink of an eye and Sandy Powell’s costume design is enviously beautiful.

At the Academy Awards nominations last week, this perfect piece of filmmaking was shut out of the competition in both the Best Picture and Best Director categories. This prompted justified outrage from the internet, with many claiming that it was “too gay” (and in my opinion, too perfect) for the Academy. But in one beautifully written piece from Queer blog Autostraddle, the writer claims that Carol’s snub wasn’t to do with lesbians at all, but rather was rather to do with the film’s proud and blatant misandry. It’s true that every male actor in the film is given a very unsympathetic role to play within the love story between Carol and Therese. Whether it’s Carol’s husband Harge threatening to take away her visiting rights of their daughter or Therese’s well-meaning but ultimately douchebag of a boyfriend Richard, the men in the film are seen as obstacles standing in the way of Carol and Therese being together. The film approaches this uncomfortable (and perhaps, for men, confronting) facet of life in a very matter-of-fact way, which may have been off-putting to the most conservative Academy members.

Furthermore, unlike other LGBTI films that have been awarded by the Academy in the past (Brokeback Mountain, Philadelphia, Milk, The Kids Are All Right), Carol is not a tragic queer story and there are no consequences for our queer characters to face in the film’s conclusion. No one dies of AIDS or gay-hate fueled violence or at the hands of Josh Brolin. No one is shamed for sleeping with Mark Ruffalo and forced to question their gay-ness. Rather, very unlike a tragic love story, it is suggested that Carol and Therese live happily ever after together.

Carol is a lovingly made film by all involved. From the nuanced performances by Blanchett and Mara, to Nagy’s measured script, to Haynes breathtakingly perfect direction, it is a masterclass in filmmaking. The exquisite love story at its centre is beautifully depicted as one for the most important and moving in cinema history. But most significantly, Carol is an incredibly important film that tells of a time in queer history that would have been a reality for many people struggling to realise their sexuality under the eyes of conservative society. Indeed, in 1952 there would have certainly been women in similar situations to that of Carol and Therese, and Carol is a film dedicated to them.

Pingback: film review: brooklyn | lip magazine

Pingback: FILM REVIEW: BROOKLYN | Jade Bate

Pingback: lipmag at the oscars: 2016 | lip magazine

Pingback: Oscars 2016 Wrap-Up | Jade Bate