film review: half of a yellow sun

The dresses are short, bright, bold. The jewellery is ostentatious: thick strings of golden pearls, diamond-and-emerald necklaces heavy and obscene. The hairstyles are impossibly neat, a series of sculpturesque bouffants. It’s the 1960s all right, but the world on screen is as far away from Mad Men as it is possible to get. As the opening credits roll to a close, a line runs across the bottom of the screen. It is Nigerian Independence Day, 1960, in the city of Lagos. There is dancing in the streets.

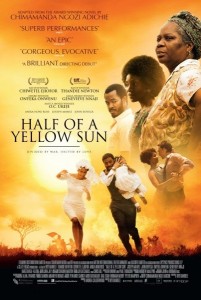

Half of a Yellow Sun, a Nigerian-English film based on the award-winning novel by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, follows twin sisters Olanna (Thandie Newton) and Kainene (Anika Noni Rose) as their peaceful, decadent lives are disrupted by the country’s descent into civil war. Olanna and Kainene have returned to Nigeria after receiving their education in England, where their postgraduate career choices are a source of shock and dismay for their upperclass family: Olanna moves in with her boyfriend, Odenigbo (Chiwetel Ejiofor), a professor disdainfully referred to by Kainene as “the revolutionary”, and Kainene puts her degree to good use and takes over the family’s business interests. Kainene also starts a relationship with an English writer, Richard (Joseph Mawle). Although they intend to go their separate ways, the sisters’ lives are forced back together by the course of the war.

Half of a Yellow Sun was, at least, billed this way, but in reality the film focuses more on Olanna and her complicated relationship with Odenigbo than it does on Kainene. Perhaps this is a by-product of how unlikeable Kainene is: Rose’s portrayal of her is snide, judgemental, self-serving, and it is difficult for the audience to muster up concern for her fate. By contrast, Olanna is a self-possessed, self-sacrificing character, simultaneously tender-hearted and unyieldingly strong; in short, a woman whom you want to see succeed, survive. In an early scene, Olanna’s aunt counsels her, “You must never behave as if your life belongs to a man. … Your life belongs to you and you alone.” For the most part, Olanna takes this advice to heart.

The film’s second act announces itself with a gunshot. Half of a Yellow Sun is an excruciatingly tense film, and its violence manages, somehow, to seem both inevitable and surprising. Any film set in this country, in this period, will unavoidably contain violence, but the film manages to create the anticipation of it even without prior knowledge of Nigerian history.

The violence in this film is not the cinematic, cartoonish violence found in action films: it is confronting, sudden, and impervious to retaliation. Newton’s performance as Olanna is extraordinary. A study could be made of her expressions alone, of her reactions as pain or cruelty are directed at her character; of the contortions of her facial features into an impassive mask; of the eloquence of her blank, deadened stare. Halfway through the film, Olanna relents to Odenigbo’s repeated proposals and agrees to marry him, something she had heretofore resisted as ‘unnecessary.’ The steps towards independence made by Olanna at the beginning of the film, when an idealised feminist character arc seemed inevitable, are somewhat undone by Olanna’s capitulation.

The curious thing about Half of a Yellow Sun is the way in which violence acts as an exterior, plot-driving force on the central love story between Olanna and Odenigbo, rather than being something the characters participate in or at all perpetuate. Odenigbo, referred to throughout the film as a “revolutionary” does nothing more revolutionary than engage in drunken political debates with his friends, in the privacy of his own home; he is never targeted by authorities for his actions, nor does he seem to suffer any worse consequences than any of the other characters, who are all impacted by the war simply for being in the wrong place in the wrong time, forced out of their homes by gangs of nameless, machete-carrying men. As Olanna and Odenigbo flee town after town, eventually reconnecting with Kainene and Richard, the conflict-plot serves to solidify them as a unit, to create a family out of strangers – it keeps them moving, but it is hard to tell if they are moved by it.

If there is a message in Half of a Yellow Sun, it might simply be that war is an impossibly large, complicated beast, undeniably difficult to comprehend. The film ends abruptly, with many threads left hanging loose; it cannot decide if it wants to be a political commentary or a romantic epic. Nonetheless, you will be swept up in the story, in concern for the characters’ fates, perhaps even by the desire to learn a little more about the Nigerian Civil War. Whatever happens, it is doubtful that you will be left unmoved by this challenging and powerful film.