film review: hannah arendt

During the trial of Adolf Eichmann, German-Jewish philosopher Hannah Arendt was unexpectedly struck by what she perceived as the normality of the man in front of her, who had been a senior member of the Nazi administration. Arendt described the ‘banality of evil’: the most evil of acts are not necessarily committed by inhuman monsters, but can be performed by ordinary humans who follow orders, neglecting thought altogether.

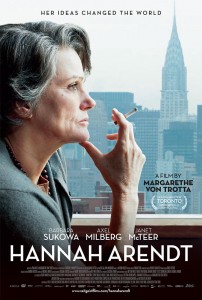

Directed by German filmmaker Margarethe von Trotta, Hannah Arendt dramatises the efforts of its title character (played by Barbara Sukowa) to cover the trial, and portrays the significant fallout following the publication of her essays and book based upon her reports. The film is a complicated, thought-provoking depiction of the life of Arendt and the period of history in which she lived and worked.

The controversial nature of Arendt’s arguments is demonstrated by the fact that the very release of this film has revived debates about her work. There is a whole world of commentary and criticism out there that can be reached by a simple Google search; the film should be watched (and reviewed) with this mind.

Hannah Arendt opens with the capture of Eichmann in South America. When the news of his trial reaches Arendt in New York, she proposes to travel to Jerusalem to report on it for the The New Yorker. Not all at the prestigious magazine are impressed by her proposal, and her husband Heinrich (Axel Miberg) worries that the experience will be too painful for Hannah, who herself spent time in a detention camp in France before emigrating to the United States.

Our heroine is determined, however, and sets off to Jerusalem. The normality of Eichmann as a bureaucrat surprises her. She insists that he acknowledges no responsibility for the murder of so many innocent people, and argues that to Eichmann, he was following orders. Once he had done so, his responsibility ceased.

Hannah returns to New York, and after the trial comes to an end she puts her thoughts down on paper. What follows is a storm of controversy: Hannah has not only shared her unexpected impression of Eichmann, but has also criticised leaders of the Jewish faith for their actions during the Holocaust. Many are horrified by what she has written, including her colleagues and friends, who say she has apologised for Eichmann and betrayed her own people. Hannah refuses to step back from her work, though, insisting she has been misinterpreted; still, only a few are willing to stand with her.

This film is centred on the amazing performance of its lead actress. Sukowa portrays Arendt in such a way that creates a complicated, multi-faceted character: the audience sees a serious side with her work, a loving nature with her husband and friends, and a strong commitment to thinking and teaching with her students. But even with all of that, there is still the hint that there is more going on beneath the surface: more memories, more internal anguish that is not articulated or even clearly visible on her face. The character portrayed is both likeable and hard to understand, vulnerable and unrelentingly tough all at the same time. Whether the viewers take her side (or any, for that matter) may be up to the individual, but the movie has not presented a simple view of this significant woman in history.

As a film, Hannah Arendt is not particularly dramatic or exciting, with little action throughout. The profundity of the story and its implications for our understandings of the twentieth-century are more than enough for one film, and the way in which the movie has been crafted allows the skilled actors and complex screenplay to do the work without fanfare. During the depiction of the trial, real footage of Eichmann is used. This in itself is a powerful approach: it provides chilling historical context and might shed light on Arendt’s interpretation.

Viewing Hannah Arendt is likely to open up a raft of questions for anyone with an interest in twentieth-century history. As a film, it is notable for its female director, female screenwriters and focus upon a female with a significant impact in history. The stories of women who have influenced their society should be brought to big screen more often and it is heartening to see this being done by female filmmakers. Yet this film is not about its protagonists’ gender, and nor should it be. The history of the Holocaust is one that must be raised again and again, and this movie certainly does that. It is only one interpretation of Hannah Arendt and her life, but it is one worth seeing.

What a thoughtful and considered review. My expectations of this film were far exceeded by the experience and it certainly provoked wide ranging discussions on the nature of evil, leadership, compliance and unquestioning acceptance of the prevailing wisdom by each of us at so many periods in our lives. Asylum seekers are a case in point.