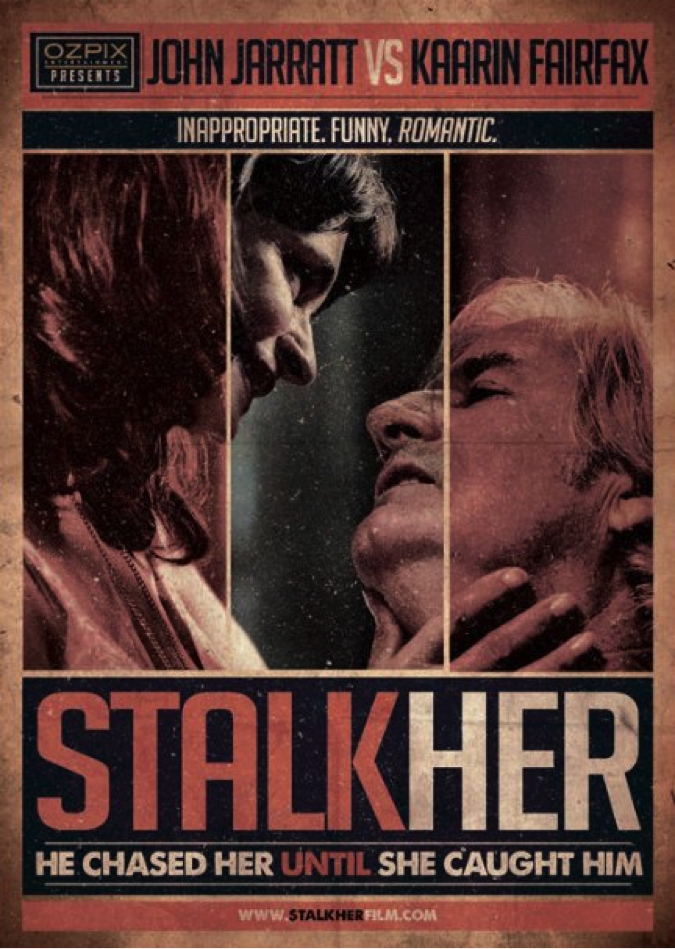

film review: stalkher

Over the past year, we’ve seen people in the entertainment industry draw attention to ageism directed towards actresses. And whether it’s Maggie Gyllehaal speaking out about being told she was ‘too old to play the lover of a man who was 55’ at 37 years old, or the writers of Inside Amy Schumer discussing their ‘Last F**kable Day’ skit, the common thread seems to be that the roles available to women in film are proportionate to their perceived sexual desirability.

Enter Emily (Kaarin Fairfax), the lead female protagonist in Stalkher. She is a nurse, a mother, and the object of obsession for Jack (John Jarratt), a pharmacist at the hospital where she works. Jack breaks into Emily’s house with a kit of medical torture devices, but is tasered unconscious before he has the chance to act on his desires. For the majority of the film, Jack is tied to a chair in Emily’s kitchen, while she bakes, or makes tea, or fantasises smashing his face in with a kettle.

Similarities can be drawn between the character of Jack, and Jarratt’s most prolific role as Mick Taylor in the Wolf Creek films, in that they are both violent and predatory men. Of Wolf Creek, Roger Ebert wrote, ‘[i]t is a film with one clear purpose: To establish the commercial credentials of its director by showing his skill at depicting the brutal tracking, torture and mutilation of screaming young women.’ But when I spoke to Jarratt about Stalkher, he noted the differences between Jack and Mick:

‘One’s a sophisticated pharmacist—he’s got a degree from uni—and the other one, you know, was born with a gun in his hand and [was] shooting pigs when he was 9 years old.’

There is also a difference between their dispositions, with Jarratt noting that Jack is ‘pretty pissed off at everything’, while ‘Mick Taylor, believe it or not, has a very positive outlook on life. Although he’s as warped as hell, he’s having the time of his life.’ These factors, among others, are what separates Jack from Mick, and are part of what makes Jack a much more realistic character. His violence doesn’t fulfil his life, but instead is the mark of something seriously lacking. And as Professor Chung’s research for White Ribbon indicates, women are much more likely to be attacked by someone they know, than by some psychopathic serial killer out in the wilderness.

Because audiences are already familiar with the violent and predatory male, Emily stands out as a much more intriguing character, and one that’s harder to label. She ices cupcakes while taunting a man tied up in her kitchen. She goes from massaging his leg when he has pins and needles, to beating him senseless. Her likes include pod coffee, apples, and inhaling amyl nitrate. She is a strange and complicated character.

Emily is also one of the most authentically sexual characters I’ve seen in film in a long time. She is not made to look anything other than what she is—a woman in her early fifties. The lines on her face are not disguised, and her outfit for most of the film, a silk nightie and dressing gown, does not feel out of place for her character. Yet, Emily’s movements, and the ways in which she presents herself, make it clear she is a woman in charge of her sexuality. Within the first few minutes of the film, she goes from being an object Jack’s desire, to the subject. She is given back her agency, and as such her sexuality is not something perceived, but something she owns.

With the majority of Stalkher set over one evening in Emily’s kitchen, the film is very dialogue heavy. Both Jack and Emily are disdainful of the opposite gender, and the dialogue between them often enforces typical gender stereotypes, the sexually driven male and the sexually manipulative female, which was a letdown for me. It’s this polarising of the genders, the battle of power between the sexes, which drives the narrative forward. But while the film divides the characters by gender, it simultaneously draws them closer through their mutual cynicism and predilections for violence. As Jarratt put it, ‘obviously these people were in dire need of counselling in the ’80s and ’90s and didn’t get it.’ It’s the similarities between the characters, rather than their differences, that really makes the film unique.

While the dialogue of Stalkher is problematic within a feminist framework, there is something to be gained from this film. With a film industry that routinely dismisses a place for mature women, Stalkher embraces Emily’s age as part of what makes her an intriguing character. It is a film that demonstrates not only that there is a place for mature women in film, but that women, regardless of age, are very interesting and complicated people.

Pingback: news round-up 31.8.15| lip magazine