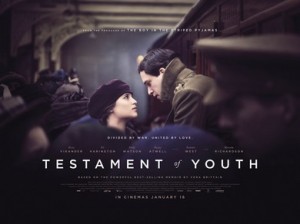

film review: testament of youth

Testament of Youth brings Vera Brittain’s memoir of the same name to life on the big screen. The film opens amid a jubilant scene: Armistice Day, 1918. In the middle of it all, a young woman stumbles, overwhelmed by the crowds and removed from the joy everyone else is seemingly experiencing. The timeline then jumps back four years, telling Brittain’s story and providing an explanation for why the end of the war was not, for her, a cause for celebration.

Published in 1933, Brittain’s memoir came to be a defining account of her generation’s experiences during the First World War. After growing up in an affluent English family and beginning her studies at Oxford (not without a battle to convince her father it was worth the tuition fees), Brittain’s own world was thrown into turmoil as she watched her brother, fiancé and childhood friends march off to war.

Feeling compelled to contribute to the war effort in some way, she volunteered as a nurse, serving in military hospitals in Britain, Malta and the Western Front. After the devastating losses of the war, Brittain returned to Oxford and later became an established feminist and pacifist writer.

The film chronicles the lead up to war as well as the four long war years and their immediate aftermath. The pre-war scenes have a slightly blurred, nostalgic aesthetic, seeming almost unreal and perhaps hinting at the horror to come. The war years have few depictions of the frontline, instead showing the chaos of military hospitals and many gut-wrenching farewells as the young soldiers return home on leave only to go back to war again all too quickly. Brittain nursed both Allied and German soldiers, and one particularly important scene depicts her holding a German soldier’s hand as he dies, a moment which will be referenced later in the film as she argues against war reparations for Germany.

Vera Brittain is played by Alicia Vikander, who is interesting and engaging in the role. While Kit Harington’s performance as her fiancé Roland Leighton was perhaps a little stiff and unconvincing, the rest of the cast were strong. Taron Egerton as Vera’s brother Edward was warm and charming, and the close relationship between the siblings was well portrayed. Dominic West was also strong in his role as their upright father who is unable to fully hide his terror at seeing his children go off to war.

The final third of the film is particularly moving, with one last devastating loss followed by the cruel silence and calm of the post-war scenes. The film uses some clever techniques to illustrate the ways Vera’s life has been changed by the war, showing the emptiness of places that were once full of laughter and friendship. The film’s final scene, though, is perhaps its most powerful, skilfully constructing the solitude of the war’s aftermath for Vera.

The memoir itself goes on to chronicle her life as a young writer and pacifist in inter-war Europe. While perhaps not as suited to the big screen, this period is worth reading about; perhaps the film will inspire new readers to pick up the memoir. The film also omits Brittain’s poetry; her fiancé’s love poems are quoted and used to further the narrative, but Brittain’s own poetry is seemingly missing. Though not her most celebrated work, a film based on her memoir could have incorporated a poem or two, such as ‘The Superfluous Woman’, which describes a feeling of loneliness after the war is over.

While at times the film is a little superficial with slightly clichéd dialogue, its overall message is strong. The heartbreaking losses Brittain experiences during the war and her sorrow at its end expose the futilities of war and nationalist aggression in the most effective of ways. The film also offers a female perspective on war, sometimes ignored in historical retellings, to the mainstream. The film does not glorify this experience nor the deaths of young men; it has a distinctly sad tone, just like Brittain’s memoir itself.