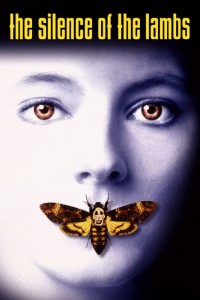

kickass feminists on film: clarice starling

Everyone knows that complex and empowering female characters are difficult to find in mainstream films. But there are some who have stood out and become the changing faces of feminism in cinema. In this monthly column, Jade Bate looks at her favourite film heroines who are strong, empowering and kick ass.

Editor’s Note: This review contains spoilers.

For this month’s Kickass Feminists On Film, we’re looking into the psychology, strength and pure awesomeness that is everyone’s favourite FBI agent: Clarice Starling from 1991’s The Silence of the Lambs.

Starling first appeared in Thomas Harris’ 1988 novel The Silence of the Lambs and its sequel Hannibal (1999), but it’s director Jonathan Demme’s big-screen adaptation of the first novel that brought the world’s attention to this extraordinary character. (This column will solely focus on Jodie Foster’s famous portrayal of Clarice Starling in The Silence of the Lambs, rather than Julianne Moore’s less-well-known depiction in the film Hannibal.)

I’ve previously presented my case for why The Bride and Katniss Everdeen should be considered feminist characters, when perhaps they aren’t so explicit in their feminist ways. But with Clarice, it’s so incredibly obvious that she’s a feminist film icon that I feel I need to hardly argue my case. But hell, let’s do this thing anyway.

Big statement, but Clarice Starling is perhaps the greatest film protagonist of all time. She’s everything a thriller heroine (or hero) needs to be: admirable, sympathetic, determined, brave and endearingly human. One can automatically place her into the category of a feminist character because, as a female protagonist, she broke the mould of what women in films could do.

The Silence of the Lambs is considered one of the greatest thrillers of all time, and it won numerous Academy Awards, including Best Picture. The film follows a young FBI pre-grad, Clarice Starling, as she assists with an investigation into the murder of four young women and the capture of a fifth by the serial killer, Buffalo Bill. In order to get into the mind of a killer, Clarice is instructed to seek out the help of Dr. Hannibal Lecter (Anthony Hopkins), an imprisoned psychopath whose nickname is ‘Hannibal the Cannibal.’

Clarice faces shockingly overt abuse and – there’s no other way of putting it – patriarchal oppression during the course of the investigation. She works in a male-dominated workforce and she is discriminated against because of her gender in ways that are both subtle and passive. In the film’s opening scenes, we see her walking through the halls of the FBI headquarters as men, both young and old, leer at her predatorily, as if they’re thinking, “Are you lost, pretty lady?”. Clarice, however, proves her worth when she – almost single-handedly – solves the Buffalo Bill case.

There are dozens of occasions when Clarice is shown outsmarting her male counterparts. When she goes to visit Hannibal for the first time in the psych ward, she is greeted with (verbal and physical) sexual abuse from both the staff and patients. The hospital’s head psychiatrist Dr. Frederick Chilton creepily tells her ‘We get a lot of detectives here, but I can’t ever remember one as attractive.’ Clarice proves herself to be smarter and more competent than Chilton, gaining Dr. Lecter’s approval and convincing Lecter to help her investigate Bill.

At a morgue in a small country town, Clarice’s boss Jack Crawford chooses to discuss matters with the Sheriff away from her because – as a woman – she may be disturbed. All the while a group of male police officers watch over her, judging. But it is Clarice who discovers vital clues that the idiotic policemen and the foolhardy Crawford overlook. Clarice is tenacious and independent in tracking down evidence, following leads and eventually rescuing the imprisoned woman and killing Buffalo Bill.

It seems like the only man in her life who doesn’t discriminate against Clarice because of her gender in Hannibal himself. He does, of course, do everything in his power to make her feel extremely uncomfortable and uneasy, as he attempts to get inside her head, but his motivations have nothing to do with gender-discrimination.

It’s interesting, from a feminist perspective, to consider the parallels between Clarice and Bill’s victims. Clarice is not only a woman, she’s also a young woman, who could be seen as just as vulnerable and helpless as the victims themselves. Seen as weak by both her colleagues and adversaries, Clarice’s strength is to use this so called vulnerability – a stereotypically negative female trait – to relate to the victims she is trying to save. It’s not just that Clarice’s male colleagues don’t possess the foresight (or intelligence) to look more deeply into clues and circumstantial evidence, but they also don’t have the sympathy or empathy for the women they are trying to rescue. To them it’s very much just another job. Yet for Clarice it is her big break, and perhaps her way to achieve self-redemption from her troubled childhood. Clarice feels as though she’s the only one who can solve the case, and remarkably and against all odds, she does. A knight in shining amour doesn’t save the captured woman in Buffalo Bill’s basement; rather a rookie female FBI agent comes to the rescue.

Perhaps what we really want from a strong, empowering feminist character is one that is not purely defined by their gender. In fact, Clarice could easily be re-written as a male role. I’m not saying that it is necessary to have so-called masculine attributes to be a strong female character, but rather it is important to show that her gender is only one aspect of her whole being. If Clarice can be defined as being strong, determined and passionate, her gender should not be brought to attention unless absolutely necessary. It is almost as ridiculous to specify female FBI agent as it is to point out that she has brown hair. Her hair colour – or her gender – are irrelevant, or even uninteresting, compared to other facets of her personality.

The real question when addressing this issue is how do we actually define what a masculine or a feminine attribute is? Physically and emotionally, Clarice is a strong character, but she also possess weaknesses that don’t ground her to one specific gender mould – she is simply human. Just because she possesses some stereotypical male attributes doesn’t make her any less feminine. But can the same be said for a male character who possesses feminine attributes? Unfortunately, that is another issue altogether.

In comparing Clarice to The Bride – who “succumbs” to motherly instincts – and Katniss Everdeen – to “yields” to love – we can see how different she was in displaying a new type of Hollywood feminism. Screenwriters have long used subplots such as motherhood or romantic love to gain an audience’s sympathy for their “strong female characters”, requiring them to conform to traditional notions of femininity in order to remain likeable. Clarice is different: she is purely motivated to be the best at what she does. She is so driven to succeed in her profession that she doesn’t see her gender as an issue, yet when she attempts to succeed her gender is the only thing that is noticed and judged on. But Clarice faces this adversity head on and accomplishes something incredible.

Clarice Starling is the definition of a feminist hero. On the American Film Institute’s list of cinema’s greatest heroes, she’s the highest ranked female character at number six. She is an all-round inspiring, unique and incredibly important character in cinematic history who strives to succeed, and repeatedly faces and conquers misogyny. In her 1992 Oscar acceptance speech, Jodie Foster described her beloved Clarice as an ‘incredibly strong and beautiful feminist hero that I’m so proud of,’ which is perhaps the most articulate, appropriate and true way to describe this extraordinary character.

Pingback: Feminist News Round-Up 02.08.14 | Lip Magazine

Pingback: kick ass feminists on film: thelma & louise | lip magazine

Pingback: LIPMAG’S KICKASS FEMINISTS ON FILM: THELMA AND LOUISE | Jade Bate

I agree Clarice is the greatest ever lead character in film. Thanks for the great article.

Pingback: LIPMAG’S KICKASS FEMINISTS ON FILM: CLARICE STARLING | Jade Bate