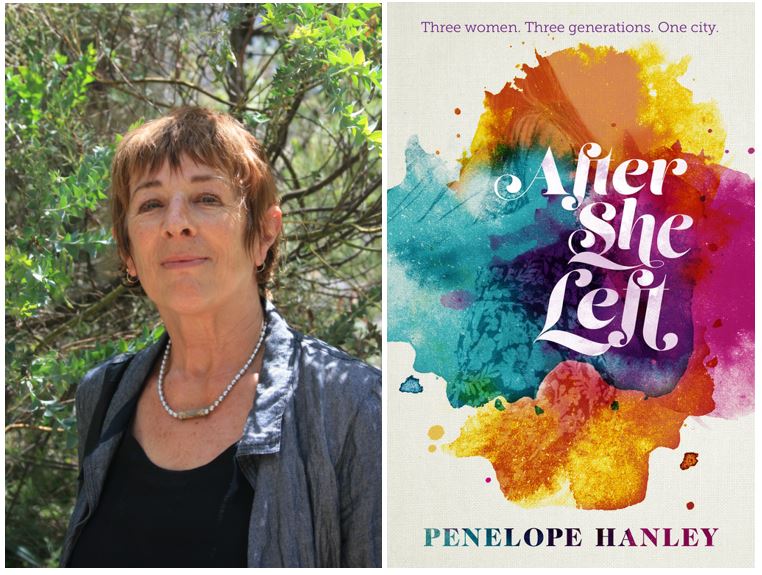

interview: penelope hanley, author of ‘after she left’

(Author Photo Credit: Janet Meaney)

Kaylia Payne chats with author Penelope Hanley about feminism, writing, and her latest novel, ‘After She Left‘.

*

How long did it take to write After She Left?

Probably about two years altogether but it was spread over a much longer time because usually I’m working full time and it’s too hard to write much fiction. I did write a preliminary version for the creative component of a PhD at the University of Canberra. But I spent so much time on the theory (I am not good at theory so that was a struggle!) plus I wrote another book during the PhD (Creative Lives, NLA, 2009) so had hardly any time for the novel component. Creative Lives was meant to take six months. I’d taken a six month break for it. But it grew organically, as these ideas often do, and the National Library people wanted me to include more and more writers in the book, to do justice to every Australian state and territory, and it took about two years!

Do you have a set writing routine?

Yes, I get up at 5:30am and write straight away, in my pyjamas (that is, once I have my coffee beside me!). My brain is sharpest in the morning. As the afternoon wears on, I’m not so good and the nights are for doing routine tasks or for movies or Netflix or dancing.

When I’m writing a book, I don’t drink during the week and I need to get to sleep by about 10:00am, otherwise I won’t want to get up, especially when it’s freezing and dark in Canberra winters! When I was writing Inspiring Australians (ASP, 2015) about those wonderful Churchill Fellows, I would walk around Lake Burley Griffin – the five kilometre ‘Bridge to Bridge’ section near the Gallery – about once a day to get exercise but also to clear my brain out of a sort of exhausting wealth of information. When I got home again, all that info. was in order. I can’t recommend walking highly enough for solving creative problems! Not to mention for maintaining back health for people who do far too much sitting.

What was the inspiration for your novel?

I used to do book reviewing. The literary editor of The Canberra Times years ago gave me a biography of French sculptor Camille Claudel and I couldn’t get her tragic story out of my head. My novel began as some What if …? questions: What if she had managed to escape and sail to the other side of the world? What if I made her Irish instead of French because my own Irish ancestors sailed to Australia and it’s more plausible because tons of Irish did that but hardly any French? (Weirdly, later on I discovered that I do have a French ancestor who came here, my paternal great grandmother sailed here from France, ending up in Cairns, of all places!)

Later, when I was awarded a PhD scholarship that allowed me to do a creative piece alongside a thesis, I resurrected this idea and plunged into researching and writing it.

Are there similarities between your own life and that of your characters?

My fiction is a combination of research, memory and imagination. My Catholic upbringing was similar to Keira’s and the relationship between her and her mother Maureen is a little similar to mine with my mother. Keira has four brothers and I had two. The two whose crises are featured in the novel – the anti-conscription law-breaking and the troubles with the bikie gang – are based closely on memories of my older and younger brother, respectively.

Alan’s house in Balmain is the Darling Street terrace I rented in the early to mid 1970s so the descriptions of its layout and décor are my memories. Keira’s group house in Woodstock Street, Bondi Junction is an actual house I used to visit where friends, a guy and two girls, lived. They were a little older than I and had far more nous than I had. I’d left home at seventeen and I remember looking at people like this and emulating them – going to restaurants like the Boka in Oxford Street with them and thinking, yes, this is a good way to live! (My parents had never gone out to restaurants or drunk wine with meals or anything sophisticated like that.)

Did you have the story mapped out before you began, or did it unfold organically?

I’d love to be one of these writers who could map out a plot and stick to it but I’m not. I need to write and research and think and dream before I know the characters and then in writing how those particular characters might behave, I get to know what they’d do and the plot develops from that.

I do make a plan a bit of the way along but that usually changes, as unforeseen things arise, such as a character who just wouldn’t actually behave that way so it goes against the grain to have them do what the plot wants them to do.

How difficult was it to jump between time periods, and how did you keep track of all the events and characters?

I made a time chart of dates and political, social and artistic events and changes so I could easily glance at it and see what was happening in a character’s life at a particular time. And when I finally got the manuscript accepted by a publisher, I had access to a wonderful editor who was good at structure, which I’m not. She said that I had a juicy plot and wonderful characters, but the book would be stronger with a better structure.

I agreed and we had a very productive meeting in Melbourne and she rearranged things and all I had to do was write new material from a different point of view of the same plot. And I integrated Olivia Kettlewell into the plot rather than having her own first-person section. When you have a woman trapped in an asylum for long periods (harking back to my inspiration of Camille Claudel) it’s hard to make that dramatic enough. It was better to have the reader see what the asylum has done to her when Maureen visits rather than have the reader be in Olivia’s mind over so many years.

You captured the different voices of the characters extremely well – how did you manage to achieve this?

Voices of particular characters usually come easily once I start writing. But the character of Maureen did take a long time. Many women of that period suffered from post-WWII society’s attitude that a woman’s place was in the home. I didn’t get a sense of Maureen’s voice for the longest time – she was trapped between the two more dramatic characters of her mother and her daughter, who were clamouring to be heard.

Deirdre was really interesting, coming from the Blasket islands and being so gifted artistically and determined to express that gift no matter what. And the third generation was active in the 1970s, an era I’m old enough to remember and that was dramatic – we went on strike for Equal Pay and we got it! (I know it was partial and women are still fighting for it now but it was a wonderful start.) We demonstrated against the Vietnam War and conscription and we ended it! Whitlam freed the draft resisters from gaol and made education free and there was child care and then divorce became easier – it really was an amazing, exhilarating time.

But that middle generation was stuck – I remember a book of the time called Brian’s Wife, Jenny’s Mum and that title succinctly expresses where those women were – stuck between the needs of men and children. Maureen, like many women of that time, had lost her identity in the needs of others. And then I guess some of my own mother’s history started creeping in and imagining a different future for her was logical when my character could take advantage of social reforms and free education. My mother really did leave my father over just the issue in the book. But arriving at Keira’s house and what happens after is total invention.

What does feminism mean to you and how did you explore this in your novel?

I was a feminist before I knew the word. Right from when I was little and seeing my mother’s life of unending work on the farm and then no (paid) work in the city – I knew that I didn’t want that. I didn’t know what I did want but I knew I didn’t want marriage and children. And I knew that I didn’t want to be a secretary when I left school. So I resisted pressure to learn short-hand and typing. When Keira tells Deirdre she can’t type, that’s what I was like. Characters respond to reading contemporary publications like The Female Eunuch etc. We see their reaction to advances like the contraceptive pill (except for Catholics – no artificial contraception – as we see when Keira and her mother argue about this). These advances and free education empower women to reach for their full potential.

What ideas do you hope the reader will take away from After She Left?

I hope they’ll be entertained and that the importance of not having secrets in a family is clear, and of being open and honest, even about difficult things. And the life-affirming idea, which I’ve seen over and over again, that life does give us second chances. It’s a cliché to say that when one door shuts another opens but it really is the way things seem to work – I find that tremendously heartening and uplifting.

Is there anything else you would like our readers to know?

Romantic attachments are a vital aspect of their growth and change. Love leads them into trouble sometimes. It takes them on a journey. Suzanne Gervay says, ‘Writing is a tough journey.’ Love can be a tough journey too. When you get close to someone it can be like a Pandora’s Box! We all have baggage. In my novel, Keira’s father was a Prisoner of War. I discovered in my research the terrible lack of support for the emotional needs of these traumatised men. Their behaviour had a big effect on their wives and families but they and their wives received no help, even when they reached out for it. There just wasn’t assistance available. Things hadn’t improved much by the time the Vietnam War came around. It’s only recently that post traumatic stress disorder has been recognised and I hope that things might be improving for returned service people.

Keira’s father is laconic and moody because of his war-time experiences. He doesn’t talk about it – but it would be better if he could.

I think we learn a lot about ourselves from our relationships and Keira’s inability to compromise becomes an issue during her relationship. Love brings up our idiosyncrasies and oddities – throws them into the spotlight sometimes – and they need to be negotiated within a relationship. This battle can be very interesting for a writer – and one hopes, her readers!

Check out Kaylia Payne’s review of After She Left here.